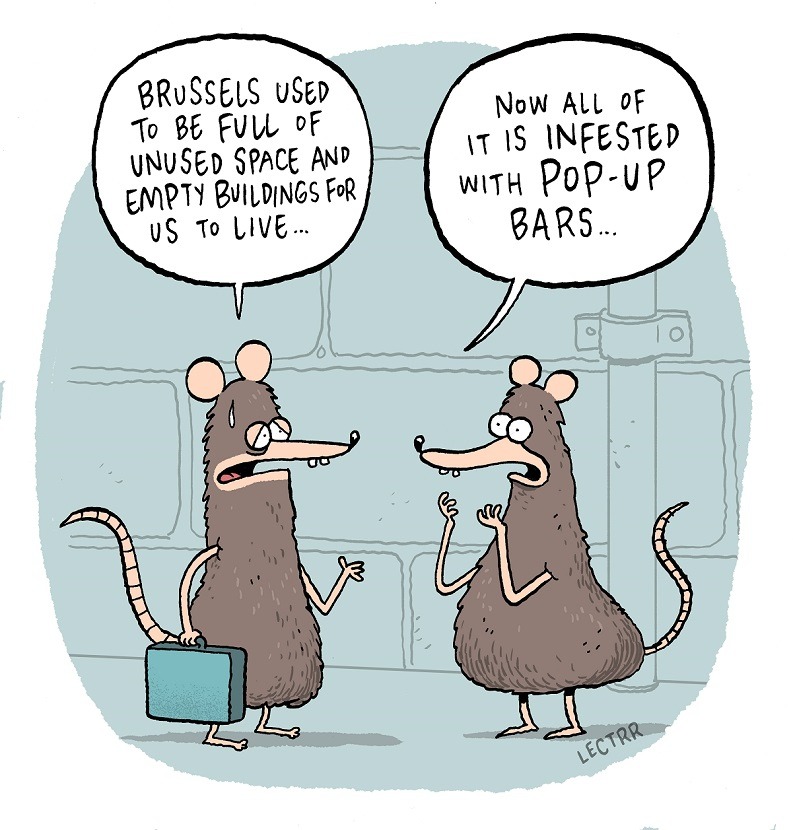

Brussels has about 6.5 million square metres of unused real-estate space.

Office buildings, abandoned lots, vacant houses and unleased apartments make up what is effectively usable space.

Some of these vacancies are due to the natural ebb and flow of landlords finding leasers or developing new projects. Other vacancies are kept empty artificially by property managers and owners in order to maintain high rental prices. This can leave otherwise usable living space entirely vacant for years at a time. For property managers, responsible for enormous portfolios, lowering prices just doesn’t make sense.

Despite all this unused space, Brussels, like other cities, is experiencing what many are calling a housing crisis. Estimates put the number of unused housing units at anywhere between 15 and 30 thousand, as well as 2 million square meters of unused office space.

Recent studies suggest that the number of homeless has doubled in the last 10 years. 41,000 people are currently waiting on low income housing in Brussels (many applying for their entire families), while up to 30% of Brussels residents pay upwards of two fifths of their income towards lodging.

The average waiting time for social housing Brussels is between seven years for a studio and ten years for a multi-bedroom lodging. In Flanders, the amount of applications for low-income housing has increased 20% in the last years. All the indicators point to increased demand for affordable housing, something that most would consider fundamental to contemporary human life.

How Did We Get Here?

On one hand, the average Belgian resident has not seen an increase in purchasing power in over a decade, while on the other, property and rental prices have increased substantially. The growing demand for social housing is not the result of increased population either. The net migration rate has halved, from around 80,000 in 2010 to about 44,000 in 2017, and population growth is stable.

The issue is incredibly sensitive, with far right politicians, to great effect, leveraging the idea that a refugee could be placed in social housing before a “native” Belgian. The underlying statistical reality is that only 6% of Belgium’s housing landscape consists of subsidized housing, less than a third and fifth of France and Holland respectively. The pressure doesn’t come from outside our borders, but rather from decisions taken within our borders.

While spending on social housing has increased in recent years (though just barely, not matching the increase in demand), perhaps the most important driver of the housing crisis is the lack of political will in order to replicate a housing market that resembles one of our neighbouring countries.

A systematic problem

Karl Marx said of Belgium that it was “…the snug, well-hedged, little paradise of the landlord, the capitalist, and the priest.” Land ownership, and indeed the landed class in Belgium is a sacred construct. Belgians love to own and build their houses. Rows of mismatching facades with their curiously long and narrow gardens dot the awkward, grey countryside, interrupted by industrial terrains, and curiously located farms.

The problem is not that the space is lacking, but rather that political pressure is oriented towards facilitating property ownership, and not necessarily providing affordable housing for people. Since the financial crisis, Belgian investment in real estate has increased dramatically, thus compounding one of the factors that have led to the current crisis.

The rights of individuals has also been reigned in, with squatting being formally illegalized in October 2017, allowing police to physically remove squatters from vacant buildings. Brussels’ most famous squat, Rue Royale 123, an office building formerly owned by the Government of Wallonia, where several dozen people had been squatting for over a decade, was sold at the same time as this court ruling. Despite protests, the residents resigned to their fate in July of this year, when judges ruled that they would have to leave by 31 October 2018.

Squatting in Belgium was formally made illegal last year. Brussels’ most famous squat, Rue Royale 123.

Clearly the economic system applied to housing in Brussels is not the optimal system for matching supply to demand. The reasoning behind this lack of efficiency is that most individuals lack the organization or capital required to pay for space, with the cost of a square meter of Brussels real estate doubling in the last decade. It doesn’t appear therefore as though the current model for allocation of real estate resources is capable of meeting the needs of the majority of people, if we presume those needs to mean safe, affordable and decent housing.

What makes this even more problematic is that the goal is not simply to stuff people into buildings like sardines, but rather to provide people with the resources they need to live enjoyable, dignified lives. The idea that human dignity is sacrosanct thus further compounds the fundamental issue, namely that there is a tremendous imbalance between what exists, and what the masses may have access to.

Addressing a systemic inefficiency

A handful of initiatives in Brussels have addressed this imbalance with a certain Belgian ingenuity. The aforementioned Rue Royale 123 is organized around Woningen 123 Logements, who are currently looking for another squat to help relocate people from the homes they just lost and the spaces they shared publicly for the creation of art and music.

One of the most visible initiatives is Recylart. When Belgian Rail decommissioned Bruxelles-Chappelle, the station between Gare du Nord and Central, a group of young creatives took over the space and turned it into a combination of venue/practice space, skatepark and bar. The space had an almost dream-like aura to it. In March of this year, Belgian Rail, who still owned the venue, determined that a public space sitting above the now defunct station was a security risk and forced the residents out. After an outpouring of local support, a new location was procured for Recyclart, and plans to reopen near the canal area are set for the end of 2018.

An organisation that has taken a more head on and systematic approach to reclaiming unused real estate is the non-profit Toestand. Rumour has it that Toestand’s origins lay in a secret party held in an abandoned movie theatre some years ago, but co-founder Pepijn Kennis can neither confirm nor deny the allegations. The organization was founded on the principles of shared experience and inclusiveness. It calls for the efficient allocation of space in Brussels. They spent their first years seeking out places where they could organize events.

One early success was a school building in the Brussels suburb of Vilvoorde. The school was scheduled for renovations, and the local authorities were open to the idea of using the space in a way that would spruce up the community. There were dance parties, painting classes and numerous events throughout the summer.

Since then, Toestand has grown into an organization that organizes over a hundred events in countless spaces, spurring activities ranging from women’s group meetings for tea to skateboarding. They receive requests daily for space. If the request corresponds to their mission, and if there is space available, they work with applicants to help them create spaces where people can gather. In 2017, they managed to organize 100 events, with the vast majority being offered for free.

Several years ago, they took their show on the road, and it has since become an annual tradition. Their longest-lasting mission to date was Termokiss in Pristina, Kosovo, a project which still runs to this day. They receive a small European subsidy for the work they do across Europe. Such has been their success on the continent that they even attracted the attention of several international newspapers.

Back in Belgium, the work and the scale at which they link people with usable space is broadening. Their most famous project is the Allee du Kaai, a multi-use space that runs along the canal across from Tour et Taxi. While they have been tremendously effective, the chronic failures of our current real estate models to address the needs of all people have not gone unnoticed.

The issue is as social as it is humanitarian, how can a society allow for large groups of people to sleep in the open atmosphere, when providing them simple shelter would have no effect on any individual or society at large? It is by proving the viability of these initiatives that these organizations spur a public discourse that may one day improve the liveability of cities across Europe and lead to a shift in public perception that regards a person’s right to sleep with a roof over their head, as a critical function of government.

By Alexandre D’hoore