Sixty years exactly since Belgium hosted a human zoo of its Congolese "conquests", the country is confronting its African history. In 1958, Belgium hosted the world fair, a chance for the nation to dazzle the international stage with displays of post-war progress across technology, society and the arts. The glittering orbs of the Atomium are one of the most iconic legacies of the Expo 58. However, another of the exhibits, for years brushed over by the history books, casts a much longer, much darker shadow over the event.

At the foot of the Atomium was an enclosure. Behind its bamboo fence, hundreds of Congolese men, women and children were put on display for the amusement of European visitors. From dusk till dawn for the two hundred days of the fair's duration, thousands came to ogle black families in their "traditional" dress.

Brussels' Kongorama, as it was known, was the world's last human zoo.

These zoos were no new form of entertainment either to Belgium or to the rest of the world. Paris, London, and New York have all hosted their share of indigenous peoples over the years: from Samoans to Sami and the Inuit.

Belgium's own history of human zoos began in 1897 when King Leopold II brought 267 Congolese to his Palace of the Colonies, located to the east of Brussels in Tervuren. These artefacts of flesh and bone were put on show alongside other "imports" from the Congo that included ethnographic objects and prized commodities such as coffee and cacao.

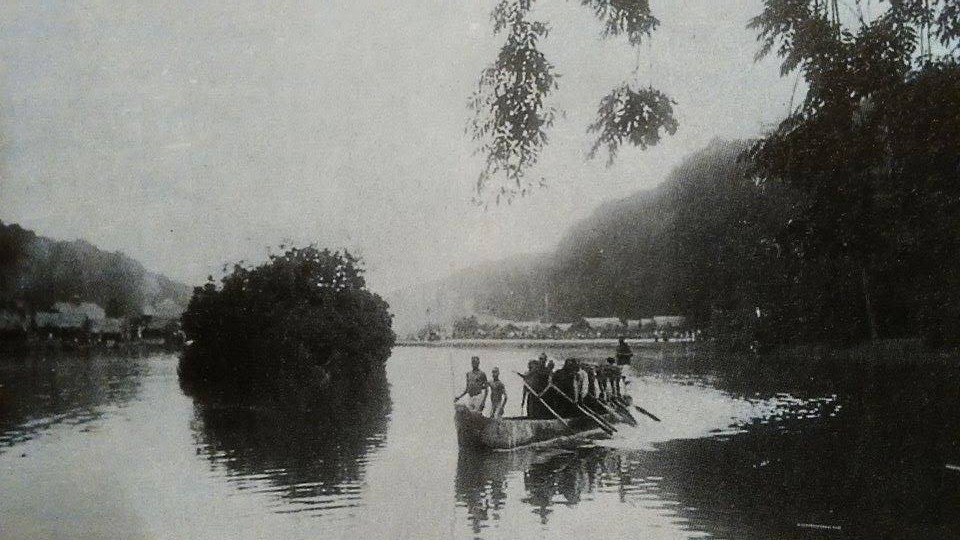

Over a million Belgians (more than a quarter of the country's then population) came to witness the curiosity, observing the Congolese dancing and drumming in their makeshift village in the palace's park or paddling their canoes across the royal lake. Over the course of the exhibit, seven of the tribesmen died from colds and flu – the traditional garments they were instructed to wear providing them with little protection from the European winter.

The last colonial museum in the world

Nevertheless the Belgian state considered the exhibition such a success that in 1898 a permanent display dedicated to Belgium's colonies was established on the site of the palace: the Royal Museum for Central Africa.

Its collection was gathered together from various sources including the spoils of military campaigns, objects confiscated as "heathen" by missionaries and the hoards of traders. According to the museum’s current director Guido Gryseels: “We were essentially a propaganda institution for the government’s colonial policy. For most visitors, the museum provided their first vision of Africa, and we have to take responsibility for the prejudices that we helped create during that time.”

The Royal Museum for Central Africa has undergone a major transformation and is set to reopen on 9 December 2018. The €75 million renovation has almost doubled the museum's size, and aimed to provide a new and more honest and transparent narrative of Belgium’s colonial past. © David Plas

For decades, visitors entering the palace were met by a huge golden statue of a European missionary towering over an African boy clinging to his feet. The plaque underneath read: “Belgium brings civilization to Congo”.

Gryseels admits: "The museum was frozen in time for many years. When I took over 17 years ago, the permanent exhibition hadn't changed since the 1950s (before Congo gained independence). That made us the last colonial museum in the world."

Taking responsibility and facing the truth

Gryseels and his team decided it was time to shake the dust off the museum's old exhibits and prejudices. "We wanted to create a new, more honest narrative. So we gathered lots of research and in 2005 organised an exhibition. This was the first time Belgium really entered into discussion about its colonial past. Many were surprised by the violence they discovered."

The team then set about dragging the museum into the 21st century. In 2013, the building was closed and started to be emptied of its 560 stuffed animals and 1460 ethnographic objects and musical instruments. Transformation began.

So how do you turn a colonial institution into a modern museum on Africa, past and present?

In its last issue, this very magazine featured an article which called for Belgium to face up to its complicity in the death of Congolese statesman and independence leader, Patrice Lumumba. But dealing with the complex legacy of colonialism is no simple matter of renaming a handful of squares and erecting a few statues.

As France prepares to send back to Africa hundreds of artefacts looted during its colonial era and Britain enters talks to lend stolen Nigerian bronzes back to the country, we must ask: how can Belgium step forward and face up to its past?

Some radical groups call for all statues dedicated to colonial leaders to be pulled down. At the Royal Museum for Central Africa, they are seeking alternatives: rather than tearing down relics, they look to recontextualise them.

A sleek new visitor centre, constructed entirely of glass, which also includes a restaurant and shop has been built. The modern, transparent facade aims to reflect the museum's transformation from an institution stuck in the past to a world centre of learning and research. © RMCA, Tervuren

On 9 December 2018, the museum will reopen its doors to the public, revealing what its website describes as an all-new "contemporary and decolonised vision of Africa". Colonial artefacts remain, yet are presented alongside an explanation of their context and how they came to be part of the museum.

Visitors will also learn how these items were used to form and reinforce stereotypes about Africa. One new exhibit looks at reality and fiction in ethnographic photography of the 1950s. This series of photos, commissioned by the Ministry of Colonies, aimed to offer a positive image of colonial order. The original photographs are accompanied by descriptions of how the traditional dances and rituals they depicted were often staged by the photographers themselves, who had been given a budget for sponsoring spontaneous performances.

Not only has the old political narrative been rerouted, so too has the entrance to the museum. Rather than accessing the collections via the palace's magnificent main entrance, now visitors will be lead through an underground tunnel and a series of rooms recounting the history of the institution itself.

Gryseels's team offered contemporary African artists the chance to respond artistically to the colonial messages of the original collection. Each room contains one of their creations. "We also included the African diaspora in Belgium in the decision making process; we consulted them on what they wanted to see in a museum about contemporary Africa," Gryseels explains.

Far from being a freeze frame of the past, the institution hopes to engage dynamically with the current situation. One part of this is its "AfricaTube" project led entirely by young people. They plan to organise screenings of films and discussions on Africa, as well as opportunities for young Belgians to come and speak via Skype to members of youth cultural centres in various African countries.

The €75 million renovation has almost doubled the museum's size and added a sleek new visitor centre, constructed entirely of glass, which also includes a restaurant and shop. The modern, transparent facade reflects perfectly the museum's transformation from an institution promoting ignorance to a world centre of learning.

"Two thirds of our staff and budget are dedicated to furthering scientific research into African culture and history," Gryseels adds proudly. "Attitudes are changing but education is crucial – especially for the younger generations, many of whom aren't aware of Belgium's role in the Congo." What has been achieved by the Royal Museum of Central Africa is a clear example of how, by looking back, we are able to take a dozen steps forward.