The success in blocking French plans for a separate Eurozone budget during 3 December’s Eurogroup demonstrates the victory of smaller states that form the so-called Hanseatic League. Formed in March, it adopted positions on Eurozone reform, but does it owe up to its name? This question will be answered by looking at the new league’s actions and the old league’s history that has been given new meaning.

Background

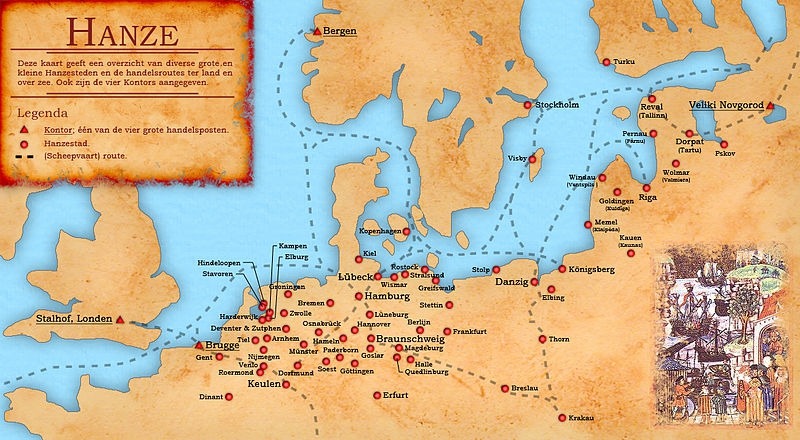

The original Hanseatic League was a loose confederation composed of merchant guilds and market towns that traded across northern Europe. It experienced its peak of wealth and power in the 13th and 14th centuries.

The new league was a Dutch initiative to reposition itself in a post-Brexit EU, where it wants to make sure interests of smaller Member States are taken into account.

Initially, the initiative was not taken seriously. The club was in a rather denigrating way considered as the club of Dutch Finance Minister Wopke Hoekstra and the seven dwarfs.

Things get serious

Just as the original Hanseatic League started small in the 1100s, the new league got more serious. Czechia and Slovakia joined ranks recently, and it claims support beyond those.

It also got vocal. Mr. Hoekstra attempted to torpedo Franco-German plans for Eurozone reform, which he called unconvincing and stated, “If this is not in the interest of the Netherlands or the Dutch taxpayer, then we are out”.

The group made the French nervous. French Finance Minister Le Maire argued it divided the EU, and weakens it versus the US and China. During the 3 December Eurogroup meeting, fierce disagreements of Le Maire and Hoekstra even required German mediation.

‘‘Hanseatic’’ vision on Eurozone reform

Many of the club took a tough stance on Eurozone reform in the past.

Earlier, it was ‘‘Mr. No’’ Rutte who stated he would not spend any penny more to the Greeks in 2012 and who in 2015 almost pushed Greece out of the Eurozone.

Moreover, the Finns demanded the Acropolis and Greece’s islands in 2012 as bailout collateral.

Thatcherite opposition

The club called for a stricter European Stability Mechanism (ESM), with more tools/powers to scrutinise/monitor Member States‘ finances, and bailouts with more strings attached, while it opposes the kind of risk mutualisation France wants.

In short: less solidarity. The agreed Eurozone plan seems to reinforce this vision on the future of the Eurozone. These attempts to block the budget and less financial help bring back memories of how Mrs. Thatcher sought to decrease the UK’s financial contribution.

Getting the name right

It is unclear if the new league’s members looked at history as the Dutch played a key role in the old league’s decline once economic interests diverted, including waging war. It also clinched bilateral deals with Livonian and Prussian Hansa towns, that undermined it.

Denmark also has a long history of wars and hostility with the old league. Altogether, it prompted the end of the old league’s wealth and trade power. Therefore, the chosen catchy name has historic flaws and puts Mr. Hoekstra’s Eurozone victory in a different perspective.

What’s in a name?

While some argue the Hanseatic League 2.0 is an example of successful decentralised cooperation, it was the old league’s looser cooperation form that put its members competing with each other. It also made it easier for stronger political entities to dismember it.

The same lack of centralised decision-making and modus operandi of Member States, in which narrow national interests dominate, is what has prevented sufficient Eurozone reform and what endangers the EU’s sustainability.

Many economists argued some form of fiscal capacity is needed to take care of asymmetric economic shocks that could result from serious financial and political crises. Nonetheless, a big group of Member States remain narrowly focused on their wallets.

As with the old league, petty town (read: member states) interests undermined the league’s (read: European Union) general interests, while greater powers overtook its trading power.

Sounds familiar? It also sheds light on Le Maire’s other comment: “I’m not sure the Hanseatic League would be in a position to face the competition with China and the US.’’

Pay now or pay later

In 2015, it was Greek PM Tsipras that refused accepting the bailout terms and almost brought down his country’s economy, only to be saved at the final hour. Yet, recently, he advised Italy recently to "better do today what they'll do tomorrow", wishing them good luck otherwise.

Likewise, the new league’s refusal to accept additional solidarity in exchange for stricter rules could backfire. The too little too late approach throughout the Greek drama is what made the Euro crisis last much longer, and arguably almost broke the common currency.

In this sense, the Hanseatic victory is a pseudo one. Rather than creating new clubs, they should focus on making the Eurozone league they are part of sustainable and viable to face competition from today’s great powers.

As much as the new Hanseatic League 2.0. secured its national treasuries, it should realise that if you do not pay today, (the financial markets will make) you pay (more) tomorrow.

By Robert Steenland