The “war to end all wars” officially ended on 11 November 1918. The centenary of the Armistice was marked by numerous commemorations around Europe. On the same day, St Symphorien Military Cemetery near Mons held its commemorative service. This is where the war began in 1914 and where the first and last casualties of the battle lie.

The Armistice is an opportunity to remember the sacrifices made in the conflict. WW1 was one of the deadliest conflicts in the history of mankind, in which an estimated 16 million people died, among them 6 million civilians and 10 million military personnel.

As much of the fighting took place on Belgian territory, this country has arguably more reason than many to recall the painful events of the “Great War”. One of the lesser-known and less spoken-about features of the war was the plight of Belgians who were forced to flee their homeland.

The outbreak of war in 1914 left many Belgians homeless and penniless. The historian Tony Kushner estimates that over 1 million fled the country, approximately one-sixth of the Belgian population. It is a fascinating story that, with the continuing asylum and migrant crisis still high on the political agenda, has particular resonance in 2018.

German troops crossing the frontier into Belgium, 4 August 1914

Just as today, the continent back then was awash with waves of refugees seeking safety and sanctuary. Back in 1914, a large part of the refugees were Belgians escaping to other countries, including the United Kingdom, France and the Netherlands, to flee the German troops. Given that it remained out of German clutches many of them – an estimated 250,000 – headed to the United Kingdom for safety. In fact, the Belgians in wartime Britain constituted the biggest single ethnic influx of refugees into Britain to date. Some of those who didn’t head to Britain made the relative short journey over the border to France, parts of which were occupied during WW1.

First welcome

At first, the Belgian refugees were greeted with open arms. In “The Reception of Belgian Refugees in Europe”, UK-based author Pierre Purseigle recalls how “a group of Belgians detraining in Northampton were met by kind-hearted ladies who were ready at the station with steaming coffee, buns and sweets. Such refugees arriving in the English Midlands brought home to us the tragedy of their martyred country.”

A source at the Belgian ministry of federal foreign affairs says that between August and October 1914, more than 1.5 million Belgians left their country, driven out by a fear of German atrocities and the violent combat that was about to engulf their homeland. These refugees were initially welcomed with a surge of generosity, whether they arrived in France, England or the Netherlands.

Many Belgians crossed the Channel for safety in England. About one in three stayed in London or its environs. The number of refugees in Wales, Scotland and Ireland together was never more than ten percent of the total Belgian community in exile in the British Isles. In the UK, the Belgians set up Belgian Refugee Committees and even had their own purpose-built villages with their own schools, newspapers, shops, hospitals, churches, prisons and police.

Approximately 250,000 Belgians sought refuge in the UK

One such community of perhaps 6,000 was based in London’s Richmond and East Twickenham, where many were employed in the munitions factory built in what is now Cleveland Park alongside Richmond Bridge. The large number of Belgian refugees caused East Twickenham to be known as the Belgian Village on the Thames.

Another was Birtley in County Durham. This small industrial village became a central hub for thousands of Belgian soldiers and their families. The residents of Birtley gained over 4,000 new Belgian neighbours during the war. Birtley was chosen as the site of two munitions factories, staffed entirely by Belgian soldiers, their families and other refugees. The resulting community was nicknamed “Elisabethville”, after the Belgian queen Elisabeth of Bavaria.

Elisabethville was the product of a unique diplomatic collaboration between the British and Belgian governments. The British built the munitions factories and the workers’ accommodation, and then turned the entire site over to the Belgian government, who then provided the workforce.

What made Elisabethville different from other factories was the intention behind it. In return for the munitions from the factories, the British government allowed a sovereign Belgian “colony” to be temporarily established in Durham. These areas were considered Belgian territory and run by the Belgian government. They even used the franc, the Belgian currency at the time.

Many British factories, particularly the war industry, employed Belgian labourers while some Belgian refugees set up their own factories such as ‘Pelabon’ in Richmond. Belgian artists, like the sculptor George Minne and the painters Valerius de Saedeleer and Gustave van de Woestijne sought refuge in Wales where they settled and worked. The symbolist poet and art critic Emile Verhaeren also found his way to Wales.

A personal story

The story of Brussels botanist Jean Massart is particularly intriguing. Ruth Pirlet, who has carried out in-depth research on the impact of WW1 on Belgium for the Ostend-based Flanders Marine Institute, said that a few months after the start of hostilities, Massart, from the Brussels commune of Etterbeek, suspended all his botanical studies because he believed “there was no time to lose yourself in speculations of pure science when the entire word’s political geography was at stake.”

Ruth said, “He subsequently devoted his time to writing and distributing all kinds of anti-German propaganda.” But his “illegal” activities did not pass unnoticed by the German forces who kept an increasingly close eye on his family.

Ruth adds, “His children had been able to leave Belgium for the Netherlands under the pretext of health problems but things were not so easy for Massart and his wife. After several failed attempts they eventually succeeded in crossing the border with the Netherlands near Bree in Limburg on 14 August 1914 under disguise and with the cooperation of an obliging customs officer.”

The couple moved to Amsterdam where they were reunited with their children and his valuable collection of information was also smuggled into the Netherlands by means of a suitcase along with clothes for Belgian refugees, says Ruth. “The whole family soon moved on to England and eventually ended up in the coastal municipality of Antibes in the south of France in autumn 1915.” Massart edited various pamphlets to “boost the morale” of the Belgian people and troops.

Other Belgian scientists spent the war in France, including biologists August Lameere and Marc de Salys Longchamps. In the summer of 1914, both went on a short working trip to the Station Biologique de Roscoff in Brittany with their families but the outbreak of war meant they could not return home. The holiday turned into a “four-year exile”.

Survival

The practicalities of just surviving were, of course, uppermost in the minds of the Belgian refugees. In France, they could obtain “reimbursements” for their savings and were allowed to use Belgian francs. Many were given accommodation for a modest rent, and they were offered jobs, often in factories. This also helped the “host” country hire low cost replacement manpower for the men who’d gone to fight. In France, for instance, there were some 10,500 Belgians employed in the metallurgical sector, so the huge influx of Belgians during WW1 also helped local economies ticking over.

France and England also received a lot of Belgian fishermen who were unable to keep on fishing and their stories have been superbly documented by the Flemish Marine Institute (VLIZ). Writing for “De Grote Rede”, Brecht Demasure said ships were commandeered and fishing boat crews effectively forced to work in shipyards in Scotland.

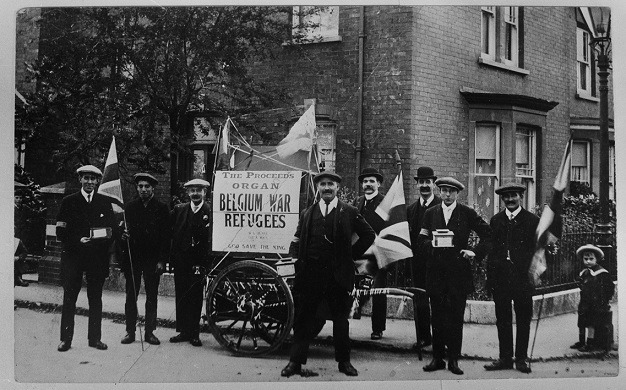

Belgian refugees at the onset of the war

The Belgian fishermen who had fled were divided into three groups and continued to practice their trade both in France and Britain. “Sometimes they actively took part in the war or provisioning the Belgian troops. They may have also been involved in clearing mines or escorting submarines,” says Brecht. Belgian crews also rescued shipwrecked British sailors, often in dangerous circumstances.

The war hit society at all levels. On 13 October 1914, the day before Ostend was overrun by the Germans, staff and pupils at Koninklijk Werk IBS, a local school, fled on IBIS VI, a steam trawler, to Milford Haven in Wales, which was to provide a refuge for them throughout the war.

During the war, specialised media was set up to keep exiled Belgians in touch with things back home. “Journal des Refugies” was one such paper for Belgian refugees in the Netherlands. Belgian historian Marie Cappart says this publication, later re-named “La Belgigue” and other similar ones played a crucial role in trying to reunite families and loved ones separated by the war. “No mention could be made of military operations, but they provided news and other information from the occupied country,” she says. “The existence of this media was short lived but important.”

The refugees’ thoughts naturally also turned to relatives who had remained in Belgium. In the wartime diary that Belgian refugee Irene Norga kept, she wrote, “If only I could have news of my parents. Where are they? Have they been mistreated? Are they unhappy? This idea fills my days and nights.”

Feelings of mistrust

But while at the start of the war, the local populations in the host countries were favourable to the refugees from "Poor Little Belgium", public opinion gradually turned into mistrust and distance. The UK and France had a different attitude towards the Belgians than the Dutch. In WW1, the Netherlands was neutral. This was part of a strict policy of neutrality in international affairs that started in 1830 with the secession of Belgium, and the Dutch were seen as being more “suspicious” of the Belgian refugees.

The Belgian foreign ministry says that at the start of the hostilities, the Belgian immigrants were generally seen as survivors of brutality and representatives of a small martyred country that had resisted a largely superior invader, in terms of both men and equipment.

Some newspapers at the time compared King Albert I and his troops to King Leonidas who, with his 300 Spartan warriors, stood up to the vast Persian army in the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC. But this empathy diminished over time. And as the war dragged on, Belgian citizens lost the goodwill of the locals and began to be considered as living at a comfortable distance from the battle fields, while their own sons and fathers were fighting on the front-line.

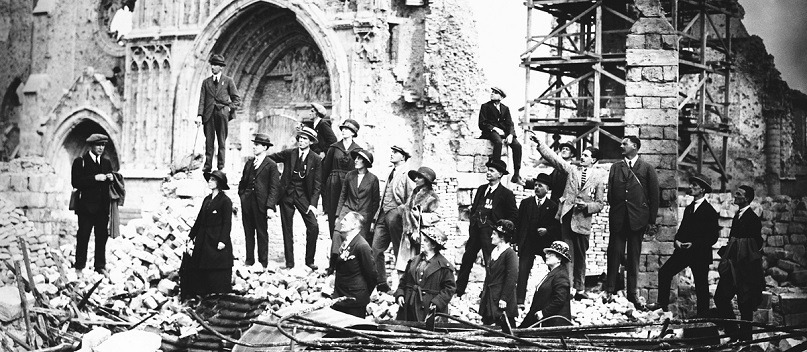

Woman looking at the destruction of Leuven. For five consecutive days, the city was burned and looted. Up to a 5th of all buildings in the town were destroyed in what was thought to be a strategy to intimidate the Belgian civilian population.

Many had expected the war to be over by Christmas but it soon became clear that it wouldn’t. Housing and jobs became an issue. Belgians in the purpose built villages in England had running water and electricity while their British neighbours did not. A feeling of mistrust and remoteness set in and even riots broke out in the UK in 1916.

In a reminder of current feelings towards migrants, the local populations thought that integrating Belgian workers into the British labour market threatened their own jobs. This reproach was based on the fact that Belgian workers accepted lower salaries than the locals, as well as longer days and working on Sundays and public holidays. Belgian refugees, having managed to flee the Germans, faced another “handicap”: they were also increasingly resented by those who’d been left behind in Belgium to face the atrocities of the occupier. “This feeling dominated throughout the rest of the conflict and beyond,” said Cappart.

Returning home

Towards the end of the war, some 140,000 Belgians were still in the UK and some decided to remain in the country that had welcomed them. But within a year of the war ending on 11 November 1918, more than 90 per cent had returned home. Those in the UK were known as the “British Belgians” and many left as quickly as they came, leaving little time to establish any significant legacy.

Belgian refugees in Somerset, England

Tony Kushner, a UK-based professor of modern history, said “They were pushed out of the country and it was not very dignified. The UK government was happy for the nation to forget and it suited the Belgian government who needed people to return to rebuild the country.” Those who came back hoped to farm the rich Flanders fields but some were even driven to commit suicide when they saw what had happened to their farms and villages. Others simply went to work rebuilding, relying heavily on German war reparations, which arrived by train in the form of fruit trees and cattle.

The Belgian government during the war was itself exiled in Le Havre, and it seriously considered having to cross the Channel to England. They never had to follow the example of many of their compatriots. A simple but poignant reminder of their sacrifice lies in a humble graveyard in Tiverton, a village in Devon in south west England. It is here where little Pieter Verlaecke, aged just seven, was buried.

Back at the start of the Great War, Pieter did not survive the rough crossing of the English Channel with his parents. His family did make it to Devon where they stayed until the end of the war before returning to Ostend to resume the family fishing business. But, for them, there will always be a little bit of England that is Belgium.

By Martin Banks