With three official languages, complicated administrative procedures and regional differences, understanding Belgium can be complicated, but luckily there are several programmes in place to assist newcomers.

Both the Dutch- and French-speaking communities offer integration courses for people who have recently arrived in Belgium. While EU residents can choose whether they wish to take part in the programmes, the trajectory is mandatory for most non-EU newcomers.

The programmes are often criticised as a means of 'Westernising' non-Belgians, but the core purpose of these programmes is to help people grasp Belgian intricacies, according to Dirk Vandervelden, spokesperson for the Flemish Integration Agency.

"We want to ensure that people are more self-reliant. We teach them skills and give them enough knowledge so that, after the course, they are able to get to work with what they have learned in their everyday lives in Belgium," he told The Brussels Times.

Mandatory for all?

Almost all people arriving in Belgium from a non-EU country who register as foreign nationals and are in possession of a permanent residence card have to take part in such a programme.

Every foreign newcomer must visit their local authority within eight days of arriving in the country to be registered in the population records.

Non-EU citizens registering with a municipality in Brussels will be referred to the Flemish (Bon - Agentschap Integratie en Inburgering) or French-speaking integration agencies (BAPA in Brussels, in Wallonia this differs per province).

All newcomers in Belgium must register at their local commune. Credit: City of Brussels

It is possible to choose which system to sign up to if registering in Brussels. In Flanders and Wallonia, the system is based on the national register and is slightly different.

When a residence permit for more than three months is ordered by the local authority, both non-EU newcomers and those who are entitled to take part in the course receive a recruitment letter receive an information document.

This is sent by Agentschap Integratie en Inburgering, – which covers the whole region excluding the cities of Antwerp and Ghent where Atlas and Amal operate – Bon, the agency's counterpart in Brussels, or its French-speaking counterparts.

They are then directed to the reception office closest to their place of residence.

In all systems, non-EU newcomers will be asked to sign a contract to ensure they are aware of the mandatory nature of the programme and that they can be penalised for not taking part.

"The integration certificate makes it possible to apply for citizenship both for those entitled and obliged to take part."

Flemish System

The Flemish programme is divided into four key pillars: social orientation, Dutch lessons, finding employment, and participation and networking.

Anyone who registers with the Agentschap Integratie en Inburgering is assigned a personal counsellor who provides support throughout the programme in the participant's own language (or with the help of an interpreter).

During the first meeting, the counsellor asks the person in question about their previously acquired skills and competencies, current situation as well as their needs. "Based on this intake information, we orient the clients towards the most appropriate offer," Vandervelden said.

Classes also take place in the evening, during the day and at weekends so the course can fit into the person's own schedule in the best possible way.

The programme includes a Social Orientation course, which touches on various topics such as living and working in Belgium, its values, culture and history, and an introduction to public services. "We focus on our customs as there can sometimes be big differences compared to other countries," Vandervelden said.

An exam must be taken at the end of this course. It consists of 41 questions: 11 cover fundamental values and 30 cover practical knowledge questions about Belgian society.

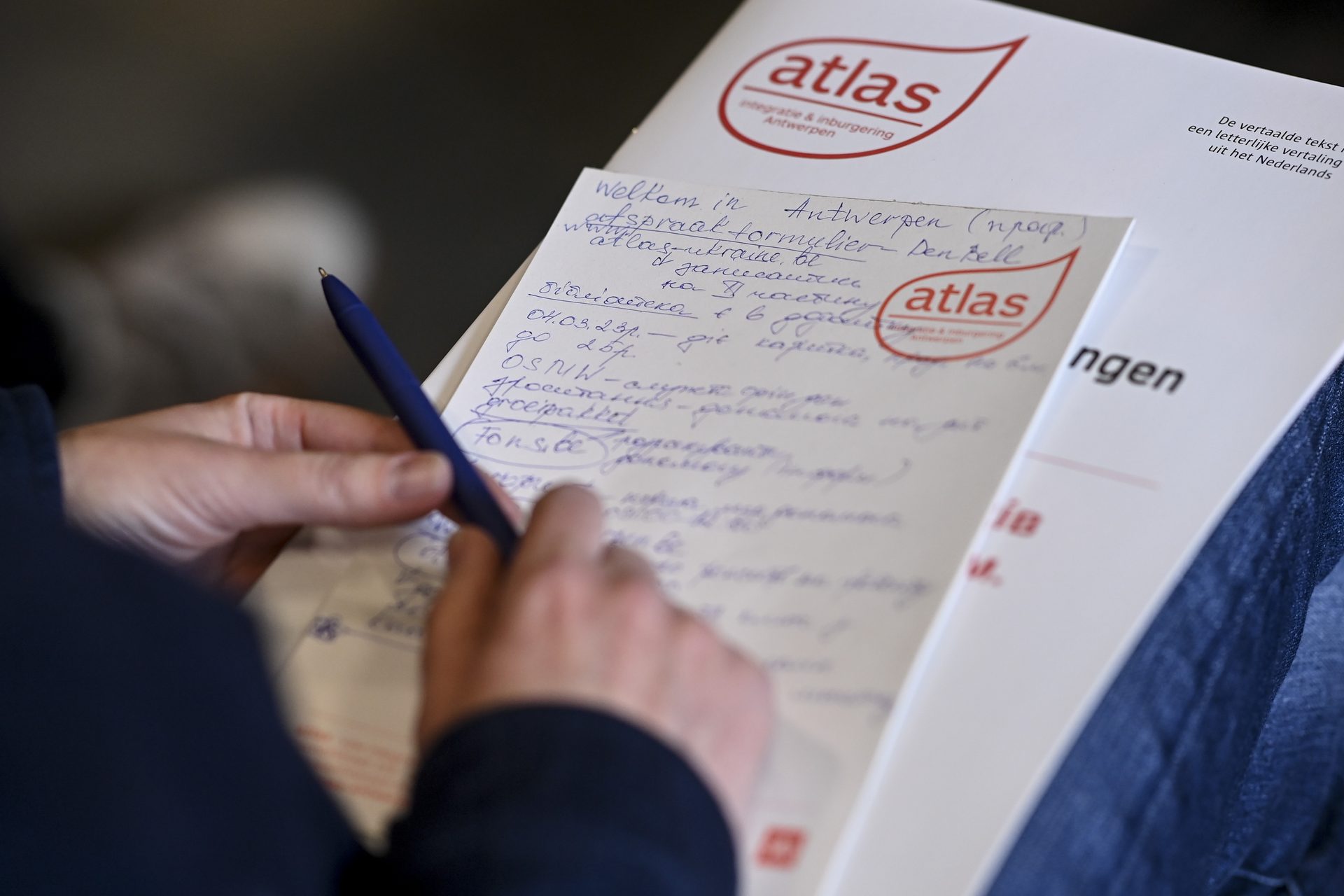

Atlas Antwerp implements the Flemish integration policy on behalf of Antwerp city. Credit: Belga / Dirk Waem

Secondly, newcomers are assessed and referred to Dutch classes tailored to their level. They can either opt for intensive classes or lessons spread over a longer period of time.

Thirdly, newcomers will be assisted in finding work and will register with employment services (Actiris in Brussels or VDAB in Flanders) with the help of a counsellor.

Finally, the participation and networking pillar requires people to "actively participate in society" for 40 hours. "This can range from voluntary work to providing a service to neighbours – the main requirement is that people have to speak some Dutch while partaking in these activities."

The programme can be adapted to people's needs and personal lives, Vandervelden explained. The Social Orientation course has various formats (online, self-study, in-person), allowing people more time to complete it if needed.

French-speaking system

A similar, more limited system is in place for those looking to enter the French-speaking community. It starts with a 'social assessment', during which the regional integration centres assess newcomers' qualifications and skills in a one-to-one interview. They may then need to take part in French language training and socio-professional orientation, depending on the results.

During this first phase, there is also a 1-3 hour class informing them of their various rights and duties in Belgium and providing information on six themes (housing, health, mobility, employment, training and education). People can also ask questions about the various administrative procedures.

In Brussels' French-speaking system, however, this course lasts ten hours and is spread out over several days.

People pictured during a French lesson in 2015. Credit: Belga / Jasper Jacobs

Secondly, people must take part in citizenship training to learn more about Belgium and its institutions through various themes. This lasts a minimum of 60 hours (spread over a maximum of four months).

The number of hours of French language training has increased since 2019, from 120 hours to a minimum of 400 over 16 months. The main goal is to attain an A2 level in the language, according to the CEFR.

Finally, newcomers are required to follow a minimum of four hours of guidance regarding socio-professional integration to access the labour market.

Non-EU nationals arriving in Belgium must complete the programme within 18 months of requesting their residence permit, but this may be extended under certain circumstances (as is the case in the Flemish system).

At the end of this process, participants will receive an 'Attestation de fréquentation du parcours d'intégration' (Integration Course Certificate of Attendance).

Costs and sanctions

Currently, both the Dutch and French integration programmes are free. However, several costs will soon be introduced in Flanders – a decision which has been heavily criticised due to the obligatory nature of the programme.

From 1 September, the Social Orientation course and test will cost €90 each. Anyone who fails the test and has to retake the course will not have to pay the course fee again, but will have to pay another €90 when resitting the test.

Dutch classes will cost a maximum of €180, depending on the number of lesson hours, and includes the test. The guidance offered will remain free. There are also exemptions, such as for people who are unemployed or in prison.

None of these costs will apply to those registered in Brussels who want to enter the Flemish system.

In Flanders, people for whom the programme is mandatory may be sanctioned if they refuse to participate in the civic integration programme and the four components.

Related News

- 30 things I’ve learned about Belgium in 30 years

- Language test for Belgian citizenship deemed 'unconstitutional'

Sanctions can range from fines to social benefits cuts. If a person cannot follow the integration programme and complete the four components because of reasons laid down in the decree (such as an illness, caring for a family member...), they will not be sanctioned.

In Wallonia, newcomers who find employment during the course are exempt so that it does not affect their working hours. Students are also exempt.