Soaring stone columns cracked and crumbling, ornate metal arches gnawed at by rust: for the past two decades, in the historic heart of Antwerp, the world’s first stock market has been fighting for survival.

On reading the words “stock exchange”, the first images that spring to mind are probably steely skyscrapers on Wall Street or in the City of London. Yet, in fact, the birth of the world’s first major economic marketplace occurred in medieval times in the Low Countries, in what is now modern Belgium. At this time, deals were brokered not by grey-suited bankers furiously shouting down telephones, but by innkeepers in their tunics and cloaks.

During the 1300s. the Low Countries were sandwiched between two trading giants: the Italian republics to the south and the German Hanseatic League to the north east. The ports of Antwerp and Bruges quickly developed into important commercial hubs for international explorers and merchants.

The Venetians brought precious gems transported from the Far East, while the Germans shipped in furs and rye from as far away as Novgorod, Russia. Innkeepers in the two cities would not only provide a roof over the heads of travellers, but would also help them exchange their goods and sell their wares. By gathering information from international arrivals, the locals were able to announce exchange rates from the various banking hubs of Europe, including Paris, Venice and London.

One of the most important innkeeping trading families were the Van der Buerse, who for at least five generations from the 1200s ran the Ter Buerse inn in Bruges. Each set of foreign merchants would have their own “nation houses” on the square outside the Ter Buerse inn, where they would come out to trade or, in bad weather, take refuge indoors to haggle, over a glass of local beer. It’s said that the pivotal role played by the Van der Buerse in brokering these early economic trades led to the creation of the word “beurs”, or “bourse” in French, meaning stock market.

Though historians argue over whether it was Antwerp or Bruges, where the trading markets first originated, most agree that it is the ‒ now cloaked in scaffolding ‒ Handelsbeurs in Antwerp that was the first ever specially dedicated stock exchange building.

Originally built in 1531, the Handelsbeurs played home to the city's chamber of commerce for almost 500 years. By the early 16th century, merchants were trading less often in real goods and more in notes containing promises from one person to lend money to another.

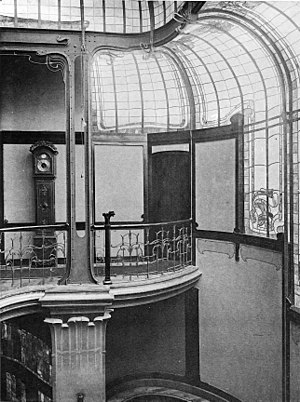

Over the course of its long history, the stock exchange has twice fallen victim to fire (first in 1583, then again in 1858) and had to be rebuilt; the vaulted neo-Gothic halls and colossal carved pillars that stand on the site today were first erected in 1872.

In 1997, Belgium’s stock exchange was transferred to Brussels, and the Handelsbeurs was abandoned. Attempts were made to use it to hold events, but in 2003 the structure was declared a dangerous fire hazard, and left for dead.

Captivated by the haunting intrigue of its ruined state, the derelict exchange has, these past 20 years, drawn hundreds of photographers and travellers, wanting to document the decline of a building that once provided the pillar of our nascent economy.

But Belgium’s first Chamber of Commerce was not quite ready to disappear into the history books just yet. Three years ago, it was decided the building should be saved, and since then plans have been evolving to turn the domed courtyard of the old marketplace into a public square with swanky bars and restaurants and trendy events spaces. During the reconstruction process, fascinating pieces of archaeology are being unearthed on all sides: from medieval tiles to Iron Age urns.

One part of the Chamber of Commerce complex, the Royal Exchange, is being turned into a luxury 139-room hotel. Also known as Den Grooten Robijn (The Great Ruby), this was where lucrative trades of gemstones and other luxury goods arriving by ship into Antwerp took place.

The hotel is expected to be unveiled in early 2020 and will be part of Marriott International. It is to be called Sapphire House, a nod to the place’s history. Original mosaics and the spectacular arched walkways will also be preserved.

So when you hand over a banknote or swipe your card to pay for a drink in the new, transformed Handelsbeurs, give a thought to the thousands of trades that took place on the stones under your feet, paving the way for that exchange and for the whole economy we know today.

Other lost and abandoned places in Belgium

The Veterinary School of Anderlecht

Dead animals pickling away in jars, rusty syringes on blood-stained trays, and lecture rooms with floors half ripped out: the abandoned Veterinary School of Anderlecht could easily be mistaken for the set of a horror film. The neo-Renaissance buildings, which have lain empty since 1991 when the school moved to Liège, are currently being converted into new apartments.

Hôtel Aubecq

One of the greatest oeuvres of the king of Belgian art nouveau architecture, Victor Horta, this opulent townhouse was torn down in 1950 and replaced by a 12-storey tower. Legend has it that the strangely shaped rooms, mostly octagonal or hexagonal, were designed in this way by Horta because he so detested the furniture of Octave Aubecq, the owner, that he wanted to force him to commission Horta to build a whole new set that would fit the space.

The demolition caused such a public outcry that the minister of public works at the time decided to preserve the main façade in the hope of one day reconstructing the building.

The grand entrance has for the past few years been gathering dust in a Brussels warehouse often frequented by squatters. Plans are afoot to resurrect the 15-metre wide granite façade by exhibiting it at the new Kanal museum by the Centre Pompidou in Brussels. Other parts, such as the stained glass windows and wooden carvings, are on display at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

Château Miranda

Also known as Château de Noisy, this fairy-tale castle in the Namur province played host to French nobles fleeing the Revolution, Nazi forces during the Battle of the Bulge, orphans housed there by the National Railway Company of Belgium and most recently American film crews. The cost of upkeeping its Gothic-inspired turrets and spires became too great and from the 1990s, it was visited only by a handful of vandals and urban explorers. The castle was eventually demolished in 2017.

Châtillon Car Graveyard

Entering a clearing in a forest near the French border, you can still see a few broken steering wheels and moss-covered exhaust pipes scattered among the leaves. This is all that is left of the Châtillon Car Graveyard. The old cars, fire trucks and ambulances laid to rest (and rust) here were supposedly abandoned by American troops stationed in Belgium during the Second World War.

In fact, most of the vehicles dated from a later period and were kept here by a local car mechanic who used them for spare parts. The cemetery of vehicles attracted so many unwelcome tourists that the owner decided to sell all of the old cars and now just a few forgotten parts remain.

By Marianna Hunt