To Stephane Dandois, an avid rock climber, it seemed like a fun idea: convert a church in the Brussels commune of Forest into a wall climbing club. Little did he imagine that his scheme from two and a half years ago might be a template to save churches in Brussels and beyond.

Last spring, Dandois and three fellow climbing enthusiasts, collectively called Maniak Padoue, won planning permission from the local council to convert St Antoine de Padoue church, a 100-year-old neo-Gothic edifice, into a dual-use place of worship and climbing club.

A small chapel will occupy an area at the rear of the church while the climbing club will take over the nave, or main part of the building. “The two spaces will be completely separate. They will hold mass once a week and there is office space for the church administration and other community activities,” Dandois says.

The conversion is underway and the climbing club is due to open in the summer. It will have a café, a section reserved for kids including a birthday party room, a speed climbing wall and a high wall, which Dandois claims will have the highest indoor climbing wall in Belgium at 22 metres.

“It’s such a beautiful building inside. We’ve left all the decorations visible. The light is crazy because of the stained-glass windows,” he gushes. The aim is to encourage locals, especially kids, to try climbing.

“We want to show that climbing is a sport for everyone. There’s more than just football out there,” he says. Special prices will be set for groups of kids from the neighbourhood. Otherwise, the club will compete on price with other climbing clubs in Brussels.

Revival movement

Dandois is not alone in seeking a new purpose for the church. Indeed, these revivalist schemes are increasingly pushing against open (and large) church doors.

“I find the climbing club in St Antoine church a great example to follow,” says Alain Mugabo, councillor for town planning in Forest town hall. “We’ll see many other conversions of churches in the coming years, particularly the large buildings. I hope they take this route so that these impressive buildings remain part of our shared cultural heritage, there for everyone.”

With attendance in Belgium plummeting, the cost of heating soaring and younger worshippers increasingly communing with their makers via a smartphone app - especially since Covid - many churches are becoming redundant.

A former church in Anderlecht, now a school's sports hall

Belgium’s complex relationship between church and state dates back to the time of Napoleon Bonaparte. Municipalities currently pay for the upkeep and restoration of Catholic churches, but with attendance dwindling communes find it harder to justify spending the money.

A revision to laws in Brussels region and Flanders is loosening the state’s financial responsibility towards the upkeep of these large, often very old buildings. From the beginning of this year, the 19 communes that make up Brussels are no longer financially responsible for the maintenance of their parish churches. Instead, the region will assume responsibility for between 30 percent and 40 percent of the upkeep of all places of worship – not just Catholic churches. The new law is pushing churches and communes to find creative solutions for these underused buildings.

“We are at a tipping point,” says Dimitri Stevens, a coordinator with Parcum, the Flemish partner in Future for Religious Heritage, a Europe-wide group seeking to preserve buildings no longer needed as places of worship.

“The new laws will alter the relationship between church and state. There’s a lot of discussion behind the scenes at the moment about how these buildings should be used, but with some high-profile examples, like the church in Forest, this debate is about to become very public,” Stevens says.

The Catholic church was initially reluctant to consider giving up its places of worship for non-spiritual activities but is now starting to see the necessity.

“To use these buildings for a non-religious purpose is the last option. Several ideas are being considered. The plans for St Antoine church are the most developed. I hope it succeeds. We are starting to consider these ideas,” says Thierry Claessens, who is in charge of all temporal, non-spiritual matters for the Catholic church in the Brussels-Mechelen archdiocese.

The first and only parish church in Brussels to be re-purposed to date is St Vincent de Paul church in Anderlecht. Built in the 1930s in the Art Deco style - a rarity in itself - the church was converted into a Catholic secondary school in 2018. Now known as Porto 1070, the conversion by the OSK-AR studio won the people’s choice award in the 2021 Brussels Architecture Prize competition, where it was described as “pioneering work that could change the educational landscape.”

Claessens agrees that even more radical solutions will become necessary. “The energy crisis isn’t forcing churches to close yet, but it will if prices stay high for years. In the near future I anticipate other solutions like St Antoine’s, with a small chapel, easy to heat,” he says.

“The problem isn’t too many churches, it’s too big churches,” he adds, saying that the dual-use model being employed in St Antoine church is “a smart solution” for some of these huge buildings.

He takes a pragmatic view of repurposing, but up to a point. “You have to be realistic,” he says. “You may have to explore splitting the churches up into apartments or offices. We support hybrid ideas incorporating a small place of worship. But not 100% apartments.”

Renewing the pews

Statistics paint an alarming picture for churches, with attendance plummeting over the past 50 years. At the beginning of the 1970s church attendance in Brussels was around 25 percent, 50 percent in Flanders and 35 percent in Wallonia.

By 2010 all regions recorded church attendance of around five percent and the numbers continue to decline, according to figures from the Church. No surprise then that churches both large and small are being closed for worship. Last year 35 Belgian Catholic churches closed their doors to their parishioners for the last time, according to church statistics.

“The situation regarding churches in Belgium is at a seriously critical point,” says Thomas Coomans, professor of architecture at KU Leuven university.

He identifies three factors that are combining like a perfect storm. The energy crisis means heating bills are going through the roof, quite literally in some poorly insulated places of worship. Communes’ budgets are squeezed ever tighter, so it’s no surprise they are reluctant to pay for the upkeep and heating of poorly attended churches.

Along with shrinking congregations, there is also the broader trend towards fragmentation in society, Coomans says. “There is a crisis of values beyond the church, leading to polarisation in society. The growth of far-right thinking in Europe is pushing communities apart,” Coomans says.

Meanwhile, Brussels is becoming more and more diverse, with over 60 percent of the capital’s inhabitants today born outside of Belgium, according to figures from the World Economic Forum.

Here is where underused churches can play a positive role, Coomans says. “If Catholic churches share their facilities with other faiths, they will be helping spread tolerance in society. You see projects happening in Berlin and other European cities. And it is slowly starting here, particularly in multicultural Brussels, between Catholics and other Christian denominations,” he says.

Around 10 percent of the 109 churches in Brussels are currently used by other Christian faiths, in particular Orthodox communities. Some churches cater for both Catholic and Orthodox congregations on a time-share basis.

Coomans supports the adaptive reuse of buildings with high heritage value. “There’s nothing new about churches being re-purposed,” he says. “It’s been happening in countries like the UK, Canada and the Netherlands for decades. Belgium is late starting this process partly because the Catholic Church is conservative and resistant to change, and also because local government plays a prominent role in the management of parish churches – it’s much more complicated than in countries where the Church is the owner and pays its own way.”

The Weavers Chapel, Ghent

But Coomans argues that the best solutions involve keeping the building in public hands. “Public reuse with a socio-cultural character is more suitable and appropriate than the privatisation of a redundant place of worship,” he says. “In my view privatising the churches is not a good thing, but ultimately it’s a decision for the owner, usually the commune.”

Altered altars

Some churches have found ways of keeping churches Catholic by handing them to immigrant communities. For example, Notre-Dame de la Chapelle in the Marolles is a Polish parish. Similarly, St Alene church in Saint-Gilles has been given to the Brazilian community.

But for diehard Belgian churchgoers, even this solution is an act of desertion. “Some say we are abandoning local Catholic worshippers. To them it’s the same thing if a church becomes a Polish Catholic parish church or if it becomes a supermarket,” says Claessens.

In Ghent, that’s what is envisaged for St Anna, a magnificent 19th century church in a mixed Romanesque, Byzantine and Gothic style, with wall paintings, usually seen only in churches in Italy. Supermarket chain Delhaize has bought a long-term lease on the 2,800 square metre building and plans to install a shop, bar and restaurant which for the moment stands empty and locked up.

Opposition to this project has come from locals, not exclusively churchgoers. A campaign was launched in early 2019 when Delhaize’s plans were made public. Celebrated violinist and Ghent resident, Mikhail Bezverkhny played on the steps of the church every day for an hour throughout 2019, come rain or shine.

His protest sparked the creation of SOS Sint Anna Kerk, a campaign group, that has fought Delhaize in the courts. “We’re not motivated by religion. It’s the art, the building itself,” said Peter Van Blanckenberg, leader of SOS Sint Anna Kerk. “This building doesn’t need to be re-purposed. It can raise funds from tourism and culture. We don’t want the city playing monopoly with our heritage.”

Van Blanckenberg and the 5,000 supporters who signed a petition opposing the Delhaize plan lost their appeal against the decision to grant planning permission late last year, but they haven’t given up. Van Blanckenberg says that Delhaize has run into various other bureaucratic obstacles and the project seems to be running out of steam. “Delhaize saw this as a prestige project, but it looks like they have lost momentum,” he says.

Blessed are the three-piece suitemakers

The risk for churches is that they are abandoned altogether, or, even worse, pulled down. While some are listed buildings, other places of worship do not have protection. “There are over 500,000 religious buildings around Europe. Many are being demolished, so any form of reuse seems positive,” says Jordi Mallarach from Future for Religious Heritage.

Some churches switched functions long ago. A 19th century neo-Gothic Franciscan church in Mechelen was sold off in 1999, and after lengthy refurbishment opened in 2009 as Martin's Patershof, a plush four-star hotel. Elsewhere in Mechelen, the Battel church has been bought by the micro-brewery Batteliek.

Martin's Patershof, Mechelen

In Antwerp, a former chapel of the city’s military hospital was converted in 2014 into a high-end restaurant, The Jane, which is widely seen as the top eatery in Belgium. In Brussels, the Les Brigittines chapel opposite La Chapelle station is now a contemporary arts centre. Notre-Dame d’Harscamp, a church in the heart of Namur was converted last year into La Nef, a concert hall and theatre.

Namur's Notre-Dame d’Harscamp is now La Nef

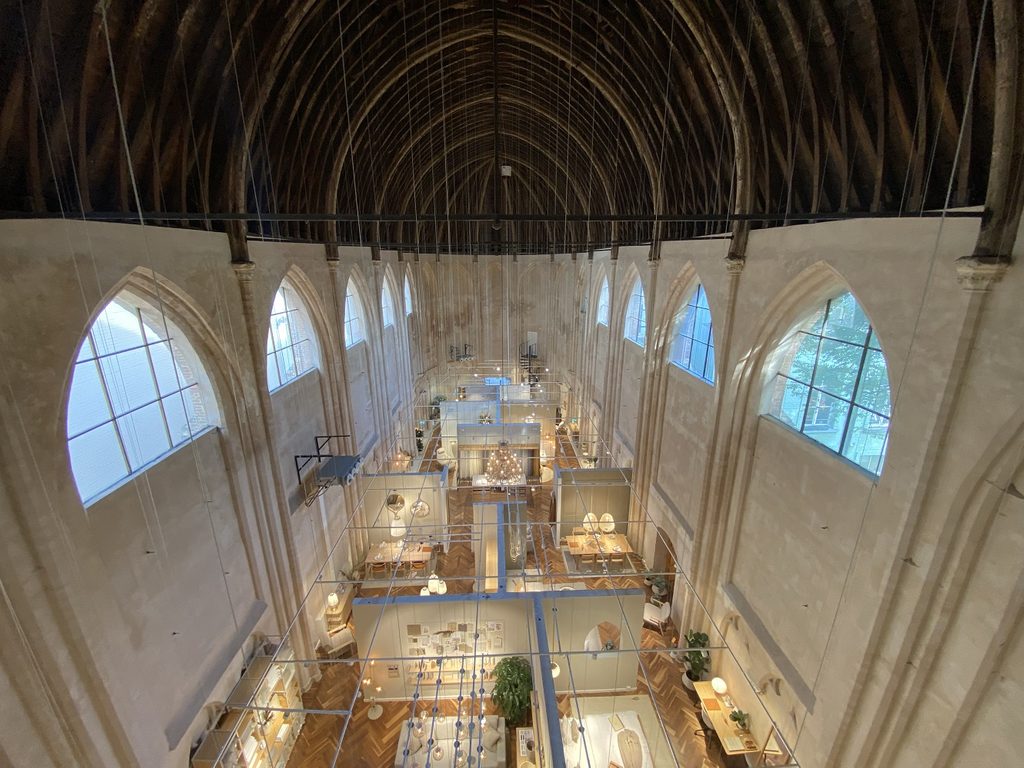

The Weavers Chapel in Ghent’s bustling shopping district has had many colourful secular tenants over the centuries, including an erotic movie hall, a butcher and a car mechanic’s workshop. Now it houses Bolia, a fashionable Danish home furnishings shop.

The church authorities are so keen on some of the schemes, including turning former places of worship into private apartments, but that is exactly what is happening in leafy, middle-class communes like Watermael-Boitsfort and Uccle.

Property developer Inside Development is preparing to submit its hybrid plan to convert St Hubert church in Watermael-Boitsfort into apartments, offices for charitable foundations and other community uses, as well as a small place of worship. The hilltop 1930s largely brick church with its imposing belfry has been empty since 2010.

“It’s too big for a church, that’s why we decided to sell it,” says Benoit Thielemans, councillor in charge of housing and public buildings in Watermael-Boitsfort town hall.

Inside Development agreed in principle to buy the church from the commune in 2016 for just over €1 million. Their first attempt to secure planning permission failed due to objections from the Region of Brussels. They plan to re-submit this year, using a different team of architects.

A different approach is being adopted in Anderlecht. The neogothic St Francis-Xavier church sits in the heart of Cureghem (a few streets from the Porto 1070 project). Like St Hubert in Watermael-Boitsfort, it has sat empty for over a decade. Instead of selling it to developers, however, Anderlecht wants to convert the building into a multifunctional community centre, with a library, café and sports hall offering circus training.

The application for planning permission is due to be submitted soon. Works will begin this year and the plan is for the re-purposed St Francis-Xavier church to open its doors again in 2024.

“It’s a project for the district,” says Fabrice Cumps, Anderlecht’s mayor. “Locals love the building. The plan is to bring it back to life so that people use it.”

While the number of churchgoers wanes, the buildings traditionally known as houses of God live on, re-purposed for a more secular society.