The European Space Agency's (ESA) ageing Aeolus satellite is set to crash to earth on Friday, but experts are still not exactly sure where.

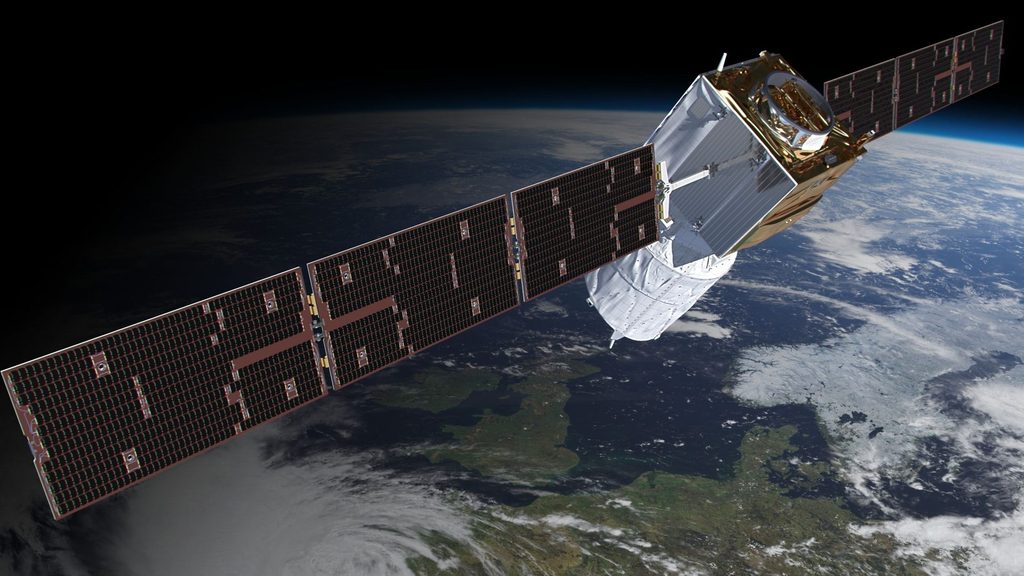

The satellite was first launched into space in 2018 to monitor wind on Earth and improve global weather forecasting and climate models. The satellite carried just one instrument: a Doppler wind LIDAR which measured winds sweeping the planet.

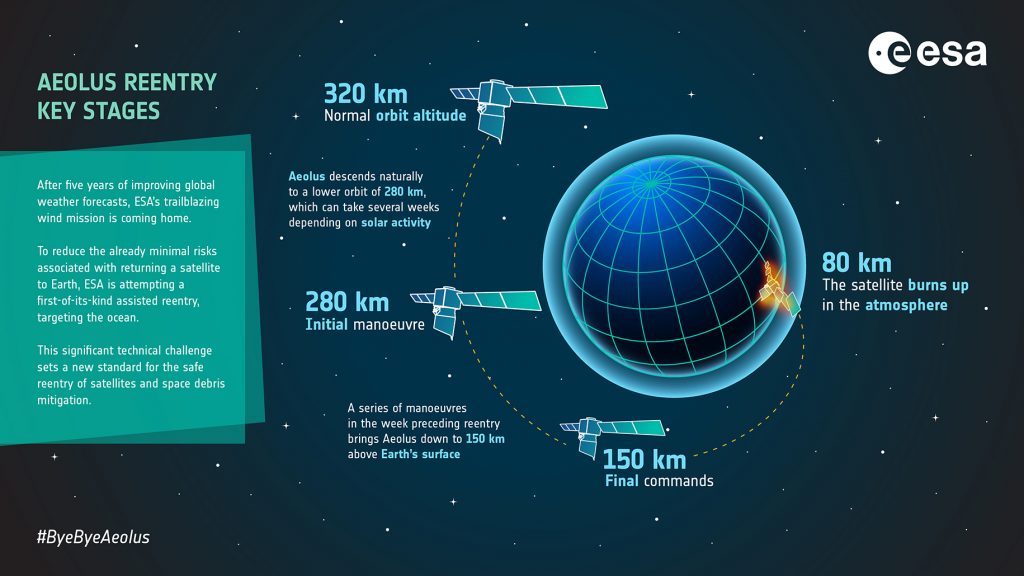

On Friday, the ESA will finalise its mission to bring the satellite back to earth. This is an unprecedented operation. The satellite was originally designed to "naturally" fall to earth in an uncontrolled reentry. Engineers and operators are going to try to push the satellite to its limits to perform a "semi-controlled" reentry, designed to reduce space debris.

Unprecedented operation

This difficult operation leaves some margin of error. On reentry the satellite "bounces" off the atmosphere. The ESA is aiming "towards the ocean." The ESA assures that the risk to the public is "very low" and that the average person would be three times more likely to be hit by a falling meteorite than space debris.

"Having exceeded its planned life in orbit, the 1360-kilogram Aeolus satellite is running out of fuel. Having ensured that enough fuel remains for a few final manoeuvres, ESA's spacecraft operators will bring Aeolus back towards our planet's atmosphere for its inevitable demise," the ESA announced.

The mission to bring the satellite back to Earth is complex. This is the first assisted reentry of its kind and "sets a precedent for a responsible approach to reduce the ever-increasing problem of space debris and uncontrolled reentries."

The satellite, after completing its mission, has been slowly falling to Earth since 19 June. The first operation to forcibly bring the satellite out of orbit started on Monday. Burning 6 kg of fuel, the satellite performed two controlled burns, bringing the satellite more than 250 km closer to earth.

"The main objectives were to lower the satellite in orbit, and check how it would behave when performing a large manoeuvre and at very low altitudes. Low-altitude operations are complex, with Earth's atmosphere and a greater gravitational pull dragging at the satellite," the ESA explained.

Credit: European Space Agency

Critical descent

On Thursday, the satellite is scheduled to make its most critical and risky burn. On its slow fall towards Earth, the ESA sets out a series of "GO" and "NO GO" checkpoints, to assess the feasibility of carrying out the controlled burn. Having received the go ahead in the morning, the satellite will start a burn to bring Aeolus to an altitude of 150 km.

Throughout the operation, the ESA team must track and monitor the up to 500,000 pieces of space debris larger than a marble already orbiting the earth. During Tuesday's manoeuvre, the satellite must rotate to thrust against the direction of its orbit and burn fuel for 32 minutes, performing manoeuvres at altitudes the satellite was not designed to do.

Related News

- Liège astronomers discover water in space

- European Space Agency request over €18 billion for upcoming missions

If the satellite survives Thursday's manoeuvre, another burn will bring the satellite to 120 km above the earth. Five hours later, it will begin to reenter the atmosphere, burning up from atmospheric friction as it does. The last of the fuel will be used to aim the satellite at the ocean.

Sometime in the afternoon, the debris will crash into the Atlantic Ocean. It is predicted that 80% of the satellite will burn up on reentry, while up to 200 kg will fall into the sea. "At around 80 km [above Earth] most of the satellite will burn up, but a few fragments may reach the Earth's surface," the ESA explained.

During its lifespan, Aeolus was described as "one of the most successful missions ever built and flown by ESA." The satellite was first tested for 50 days at the Liège Space Centre in Belgium, before blasting off into space from French Guiana.

Follow live updates of the Aeolus reentry here.