From 4 October 2023 to 4 February 2024, the BELvue Museum's Looking for the End of the World exhibition celebrates the 125th anniversary of a dangerous and pioneering antarctic expedition.

The team, led by Belgian expedition commander Adrien de Gerlache, collected scientific data and samples that still today allow experts to better study how the climate has changed in over a century.

The free exhibition highlights the expedition, the consequences of climate change, and the fundamental and symbolic role of the whale through a series of historical documents, photographs and objects from the expedition. It also has educational maps, interactive displays, infographics and input from experts.

It is an initiative of the King Baudouin Foundation in collaboration with the non-profit de Gerlache Polar Memory (run by descendants of Adrien de Gerlache himself), among others, and was curated by famous Flemish meteorologist Jill Peeters.

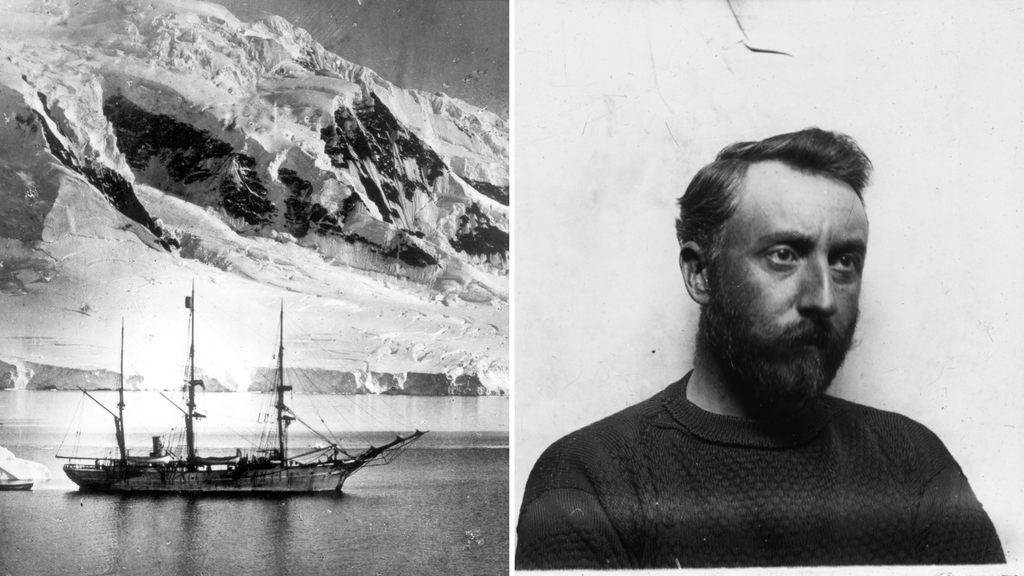

La Belgica. Credit: de Gerlache Polar Memory asbl/vzw

La Belgica

Over a decade before Norwegian Roald Amundsen became the first to reach the South Pole, de Gerache was part of the Belgian-led crew on the Belgica steamship that would be one of the first to explore the Antarctic continent, unexpectedly making them the first people ever to spend a winter there, too. The team of nineteen was surprisingly international (hailing from six countries) and surprisingly young (the average age was 27).

"People didn't know much about Antarctica besides that it existed," Gerald de Hemptinne from the King Baudouin Foundation explained.

The Belgica left Antwerp on 16 August 1897, and reached Antarctica roughly five months later. Then, in May of 1898, the Belgica became stuck in the ice, forcing the crew to spend an unplanned additional year at the mercy of the harrowing cold. This year of desperation, however, allowed to make groundbreaking scientific observations and discoveries that scientists continue to depend upon today.

La Belgica stuck in ice. Credit: de Gerlache Polar Memory asbl/vzw

"They had to collaborate with their ice cage," Henri de Gerlache, a descendant of Adrien de Gerlache, said of his ancestor's crew. And it was, by all means, a cage: the crew not only had to survive the freezing temperature, but also endure the constant noise of the ice grinding against the wood of the ship. They survived on pure grit and their cook Louis Michotte's idea to hunt and eat penguins, which kept the malnutrition at bay despite the largely unappreciated taste of the meat.

The crew hoped that the following summer might thaw the ice enough to free them, but summer arrived and the Belgica remained stuck. Ultimately they physically hacked themselves out, narrowly avoiding a second and potentially fatal winter. They returned to Antwerp in November of 1899, one year behind schedule and only two crew members short: one had been washed overboard during a storm, and another had previous health problems that led to death by exhaustion.

By then the team had collected so much biological, meteorological, glaciological and geological data that it took over forty years for all of their discoveries to be published.

What happens in Antarctica doesn't stay in Antarctica

The Belgica was not born as a scientific steamship. In fact, it was originally a Norwegian whaling boat, and after being purchased for the expedition it was converted into the vessel that would prove capable of surviving over a year trapped in pack ice.

It's origin as a whaling boat is surprisingly appropriate for the BELvue Museum's Looking for the End of the World, which dedicates a large portion of the exhibition to the whale as a physical and symbolic representation of how humanity has disrupted the environment, including the rapid acceleration of climate change.

Credit: BELvue Museum

"Unfortunately, what happens in Antarctica doesn't stay in Antarctica," Hemptinne said, pointing to the fact that the rapidly melting ice caps are just a symptom of a greater problem that is impacting the rest of the world, as well.

In fact, the Belgica's findings were important as they created a basis of data to which scientists can compare today's findings and better understand how Antarctica – and consequently, the rest of the world – has changed over the course of 125 years. For example, visitors to the museum are immediately faced with a shocking statistic: today there is only 5-10% of the whale populations that existed at the time of the Belgica.

Related News

- 38th Francophone Film Festival of Namur kicks off tonight

- Art and events in Brussels and beyond

- Royal Library to build glass elevator to rooftop overlooking Mont des Arts

The exhibition, however, also provides some behavioural solutions that empower individuals to lessen their own environmental footprint by, for example, eating less meat, taking public transportation and buying used goods rather than new ones, among other things.

In the end, the whale is also a metaphor "for the real hope of a new, liveable world. Because – as the exhibition makes clear – if we save the whale, we also participate in saving the planet."