On 23 August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, named after their foreign ministers, which divided Eastern Europe and led to the outbreak of the second world war a week later. 80 years later this notorious pact is still subject to different interpretations and casts its shadow on current events.

At a recent conference (15 October) in the European Parliament, Estonian, German and Russian experts discussed the historical context of the pact and if any conclusions can be drawn for international relations today. The conference was arranged by MEPs Marina Kaljurand and Sven Mikser of the Estonian delegation of the S&D group.

Estonia and the other Baltic countries were occupied by both Soviet Union and Nazi Germany as a consequence of the pact which divided Eastern Europe in spheres of influence between the two totalitarian states. Estonian law professor Lauri Mälksoo explained that the pact, where two empires secretly divides other countries, was illegal even for its time.

If Nazi Germany and Soviet Union did neither act legally nor morally, did they act in their own best interests? The result test shows that Stalin, who still is regarded as a great military strategist in today’s Russia, totally miscalculated Nazi Germany´s intentions and was taken by surprise when Germany attacked an unprepared Soviet Union on 22 June 1941.

According to American historian Timothy Snyder, the Nazi mass killings of Jews started at shooting pits in areas which Nazi Germany conquered from the Soviet Union. His lesson is that most killings took place in the “blood lands” in Eastern Europe where the governments had been destroyed and which were occupied twice by the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.

Communist Soviet Union under Stalin and Nazi Germany under Hitler were ideological death enemies. According to common opinion, Nazi Germany wanted lebensraum in the east. Still the two powers signed a non-aggression pact which scared the Western powers from attacking Germany after it had invaded Poland on 1 September 1939 until 10 May 1940 ("the "phoney war"), when Germany attacked Western Europe. Then it was too late.

German history professor Claudia Weber disclosed that the pact was not even secret in 1939. But the Western powers, Britain and France, showed little interest in Eastern Europe and were caught in the defence doctrines of the previous world war. They had superior man power and their tanks and war planes matched the best German ones but preferred to wait for the German attack.

Russian history professor Andrey Zubov told The Brussels Times that ideology had nothing to do with the pact. Both the Nazi and Soviet regimes were criminal, hungry for power and world dominance. A pact between them was inevitable in the political-historical context after the first world war. In his view it was not a matter of winning time for Stalin and preparing for war against Nazi Germany.

The very existence of the pact was a long time denied by Soviet Union and the original pact in Russian language was found only after Russian president Putin ordered the archives of the ministry of foreign affairs to retrieve it.

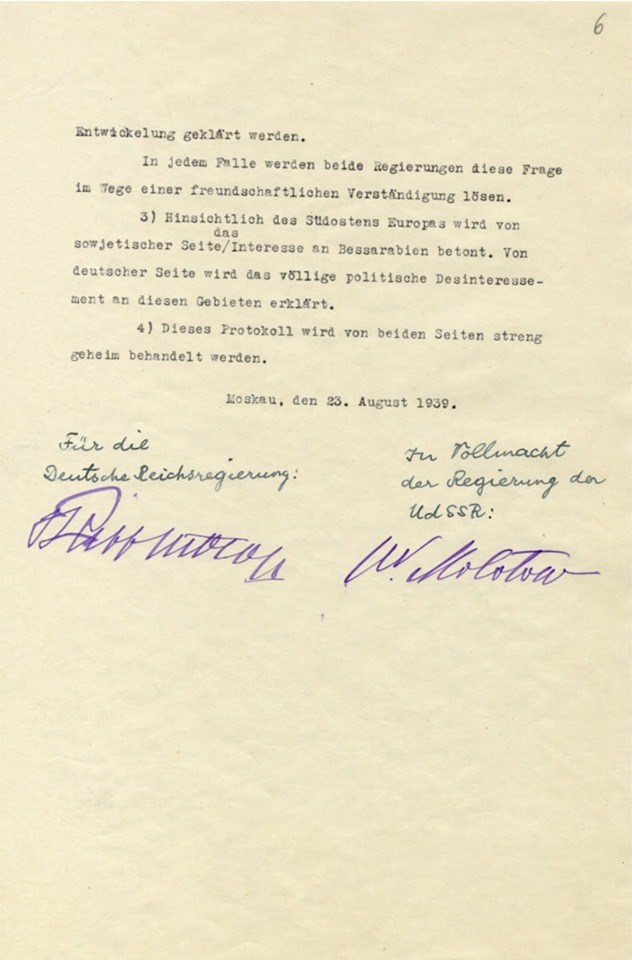

Ribbentrops and Molotovs signatures on the Secret Additional Protocol to the pact. “This protocol shall be treated by both parties as strictly secret.” The protocol was disclosed this year in Russia.

Swedish journalist Michael Winiarski writes (Dagens Nyheter, 21.8.2019) that the Russian ministry protested last year against the news agency AP for describing the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany as “former allies”. According to opinion polls every third Russian has never heard about the pact and a fifth do not believe that the pact greenlighted the Nazi German invasion of Poland.

After the end of the war, many Europeans continued for decades to suffer under totalitarian regimes. The European Commission commemorates every year a day of remembrance for the victims of all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes. This year also marked the 30 years of events in 1989 when citizens of Central and Eastern Europe broke through the Iron Curtain and accelerated its fall.

The Baltic Way demonstration took place on 23 August 1989, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Two million Baltic citizens formed a 600-kilometre human chain all the way through Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. It was a peaceful demonstration that united the three countries in their drive for freedom.

In a statement, the Commission recalled that living history is turning into written history. “We must therefore keep those memories alive to inspire and guide new generations in defending fundamental rights, the rule of law and democracy. It is what makes us who we are. A Free Europe is not a given but a choice, every day.”

EP resolution on remembrance

The conference on the pact follows a resolution adopted by the European Parliament in September on “the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe”. The resolution was supported by the major political groups, PPE, S&D, Renew Europe and ECR.

History professor Andrey Zubov (to the left) and law professor Lauri Mälksoo at the conference. © Silver Meikar

The resolution states that remembering the victims of totalitarian regimes and recognising and raising awareness of the shared European legacy of crimes committed by communist, Nazi and other dictatorships is of vital importance for the unity of Europe and its people and for building European resilience to modern external threats.

Without mentioning some of its own MEPs, it condemns the fact that extremist and xenophobic political forces in Europe are increasingly resorting to distortion of historical facts, and employ symbolism and rhetoric that echoes aspects of totalitarian propaganda, including racism, anti-Semitism and hatred towards sexual and other minorities;

It calls on the EU Member States to condemn and counteract all forms of Holocaust denial, including the trivialisation and minimisation of the crimes perpetrated by the Nazis and their collaborators, and to prevent trivialisation in political and media discourse.

The resolution also declares that European integration as a model of peace and reconciliation has been a free choice by the peoples of Europe to commit to a shared future, and that the European Union has a particular responsibility to promote and safeguard democracy, respect for human rights and the rule of law, not only within but also outside the European Union.

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times