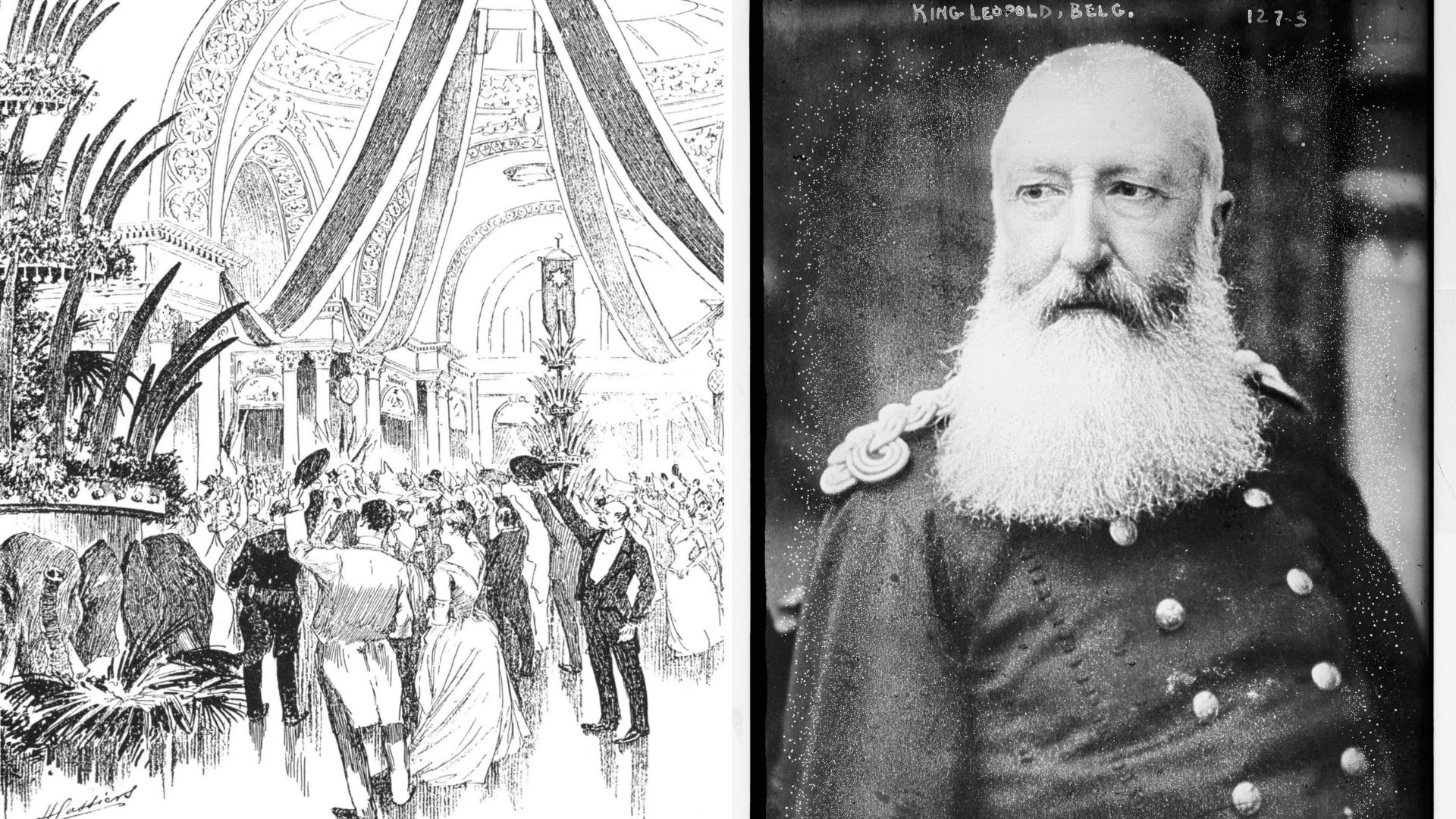

On this day, 18 November 1889, King Leopold II organised an anti-slavery conference in Brussels. Rather than being a key moment for abolitionism in Europe, it helped secure the 'Scramble for Africa'.

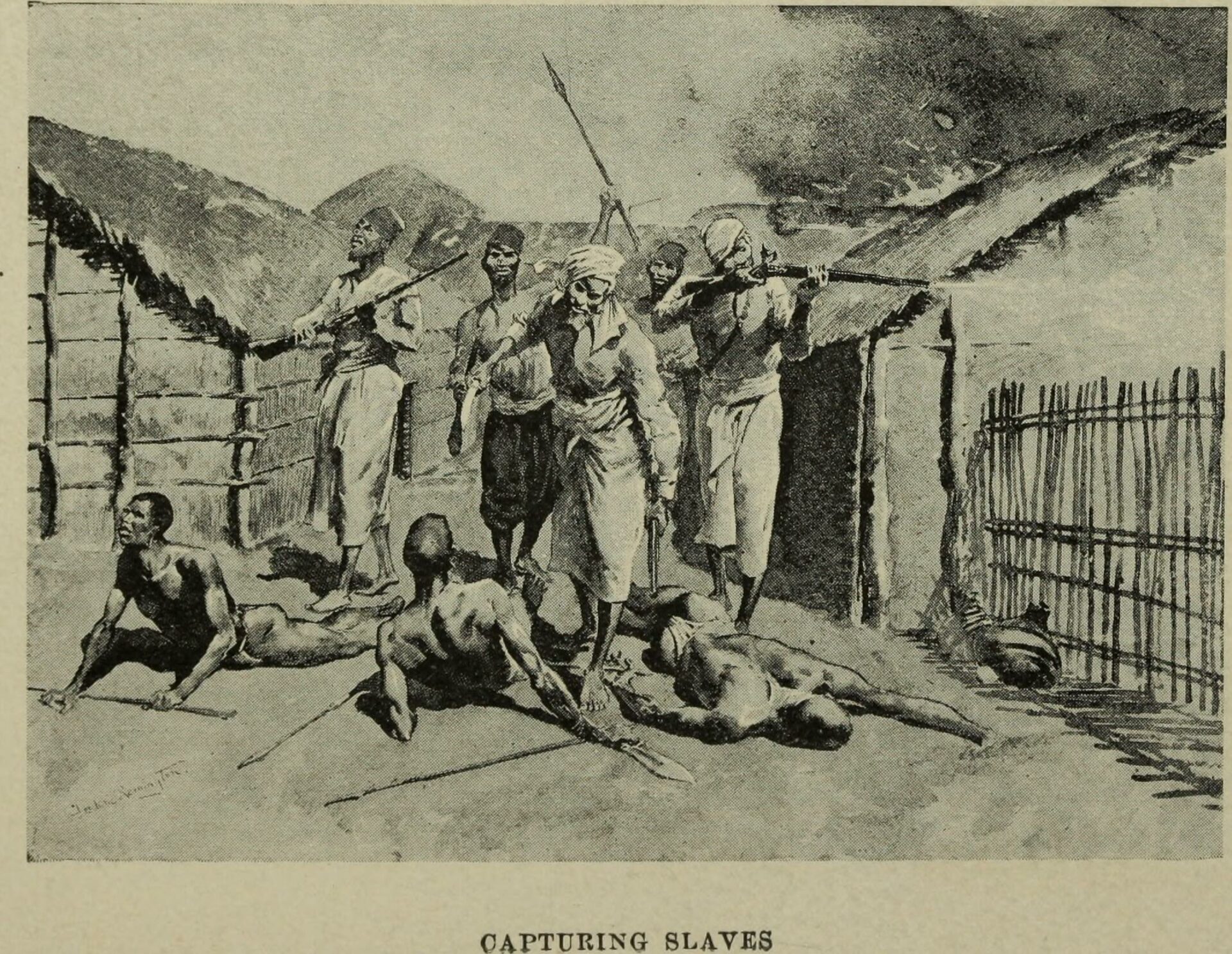

Throughout the 19th century, the anti-slave trade movement was in full swing in Europe. A consensus was growing on the human outrage of slavery and by 1889, it had been made illegal across Europe. Yet on the African continent, slave hunters and traders were still operating in central and eastern regions.

At a largely forgotten conference, 17 world powers gathered in Brussels during the winter of 1889 to embark on an eight-month congress which paved the way for the Brussels Conference Act of 1890.

While European powers achieved a ban on the slave trade in Africa, they used the conference as a pretext to reinforce colonial practices, notably in Congo, through African trade and "civilisation".

Ahead of the conference, the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society outlined some of its ideas which would be discussed: the improvement of international law to help enforce the ban and the ultimate abolition of slavery itself.

At the time, the Arab slave trade exported black slaves from the African mainland to Turkey, the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba, the coasts of Persia and Arabia, and, under a somewhat disguised form, to Madagascar, the Comoros, Réunion, and other islands.

Berlin Conference II?

The idea for a conference had come from the Anti-Slavery Society in Britain, which invited King Leopold II to organise a conference to limit slave trade on land and sea, arms trade and liquor traffic. Leopold was chosen as he was seen as "the soul of the great exploration movement and of African civilisation," L’Independence Belge reported that year.

But crucially, at the Berlin 'Scramble for Africa' conference of 1884-85, Leopold had promised to abolish the slave trade in central Africa to convince the international community to become the absolute monarch of the Independent State of Congo.

Cartoon depicting Belgian King Leopold II in the middle, German Emperor William I on the right, and a crowned bear (representing the Russian Empire on the left). Text translation: 'When will the masses awake?'

The organisation of the 1889 conference in Brussels provided the perfect ethical and humanitarian cover for Leopold II’s plans to tighten his despotic rule. He was also the only head of state representing two separate entities in the conference: Belgium and Congo.

The full list of participants: Germany, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, the Independent State of Congo, the United States of America, France, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, Persia, Portugal, Russia, Sweden and Norway, Turkey and Zanzibar.

Colonial control for anti-slavery

After much deliberation the Brussels Conference Act of 1890 was adopted, coming into force 1 April 1891. It effectively ended the Arab slave trade in Africa.

But historians have argued the agreement did not contain enforcement mechanisms to end slavery – notably forced labour – in which Europeans exploited Africans. This left the door open for colonial powers to enforce violent regimes in Africa.

The first article of the convention sets out the strategy, by saying it would place "administrative, judicial, religious and military services in the African territories under the sovereignty or protectorate of civilised nations."

This pretext was then used as a means of laying down colonial infrastructure. Delegates in Brussels agreed to roll out roads, railway lines, stations, telegraph lines, and fortify positions on the coast.

All of this would be heavily policed to secure the routes and notably restrict "the importation of firearms, at least sophisticated weapons and ammunition, throughout the territories affected by the slave trade."

The slave trade in Africa (1893)

While aimed at slave hunters and traders, this measure also restricted access to weapons for any potential rebels against European rule. There had even been a Belgian proposal to maintain arms trading as a State monopoly, with the power to resell to individuals with satisfactory guarantees.

Leopold's crusade

Through conniving political manoeuvring, Leopold II was able to establish import duty on the Congo River to be paid to him. Writing in The Times in November 1890, British Lord Wolseley posited that without it "the Congo State cannot raise the revenue it requires to carry out its glorious anti-slavery policy."

In essence, European leaders like Leopold II were using this fight to open up Africa for commerce, trade and civilisation missions (the racist political force behind colonialism). No one would benefit from this arrangement more than Leopold II, who tightened his tyrannical rule over Congo.

From 1892 to 1905 the Belgian Congo was the source of countless atrocities against Congolese people, with Leopold's officers carrying out mutilation, forced labour, rape, and looting.

Ironically, Baron Auguste Lambermont of the Belgian delegation had opened the Anti-Slavery Conference with these words: "Feelings of humanity and commiseration erupt on their own when we deliberate with our feet in the blood."

"Today in History" is a historical series brought to you by The Brussels Times, aiming to take you on a trip down memory lane for newcomers and Belgians alike, written and compiled by Ugo Realfonzo.