The mission early on January 20, 1943, was simple enough.

Jean de Selys Longchamps and fellow Belgian pilot André Blanco had orders from the Royal Air Force (RAF) to strafe an enemy-controlled rail junction near Ghent. As soon as they’ve hit the target, they’re to return to their coastal base in Kent as quickly as possible to avoid the risk of being intercepted by the Nazis occupying Belgium at the time.

They’ll be back in time for breakfast.

But De Selys has other ideas.

The mission is quickly accomplished but instead of turning back as planned with his wingman, he heads in the opposite direction – for Brussels.

For weeks, de Selys has badgered his RAF bosses to let him carry out a raid on his home city, but his efforts to persuade them fell on deaf ears.

He knows it’s risky and he’ll be in trouble, but he might never get this chance again.

Pushing his Typhoon plane to the limit, he soon sights the enormous dome of the Palais de Justice. It’s just turned 9am.

Skimming rooftops, de Selys thunders past the Royal Palace before turning down Rue de la Loi towards the Cinquantenaire. As he roars over the 30-metre-high triumphal arch, he nearly clips the bronze chariot on top of it. He later tells Raymond Lallemant, another Belgian pilot, that “the horses reared up” as he passed.

In the streets below, people cannot believe their eyes. The lone plane is flying so low they assume the pilot is in trouble. Instead, de Selys holds it level and pulls right. He doesn’t need a flight plan. He knows precisely where he’s going, turning up Avenue des Nations (now named Avenue Franklin D. Roosevelt) towards the Bois de la Cambre.

Pulling back the throttle to cut the Typhoon’s speed to 200 km/h, he turns into Avenue Émile De Mot and suddenly his target is bang in front of him: 453 Avenue Louise. The Brussels headquarters of the Gestapo, the secret police of the Nazi German occupiers.

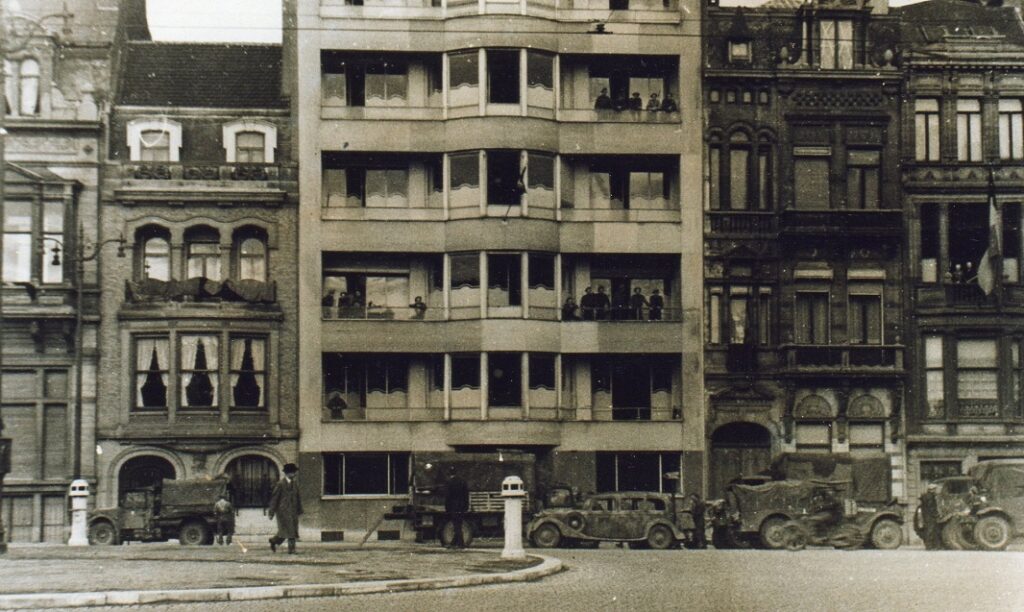

453 Ave Louise then

He punches a button and a hail of shells rain down from the plane’s four 20mm Hispano cannon. He sprays the entire façade of the 12-storey building, from top to bottom. Glass and masonry fly in all directions.

Lifting his cockpit canopy, de Selys then releases two huge Belgian and British flags, followed by dozens of small Belgian tricolours, before heading back to Britain to face the music.

His unauthorised attack leaves a scene of total chaos and claims the lives of four Germans including SS Sturmbammführer Alfred Thomas, the man responsible for sending more than 18,000 Belgian Jews from Mechelen to their deaths at Auschwitz.

The collaborationist press tries to cover up the raid, but it doesn’t take long for the public to discover that a Belgian pilot was responsible for the attack. De Selys becomes an instant national hero.

But barely seven months later, de Selys is dead, tragically killed while attempting to land at RAF Manston after a mission near Ostend.

Dispelling myths

In the 80 years since his raid on the Gestapo HQ has become the stuff of legend. Stories abound about it – some inevitably embellished or even untrue. Much less is known about de Selys himself.

That is set to change with the release of a new, meticulously researched biography, ‘Sur les traces de Jean de Selys Longchamps – Une vie au galop’, which reveals many hitherto untold aspects of his life and wartime service, as well as dispelling myths about the attack.

De Selys standing atop a Hawker Typhoon, 1942

I meet its 60-year-old author, Marc Audrit, at the Maison des Agents Parachutistes in Ixelles, a club set up by former secret agents who served with Winston Churchill’s Special Operations Executive during the war.

Audrit grew up in what he describes as “a world where World War II and patriotism were key dimensions”. His father Georges, a member of the Belgian resistance, was arrested in Liège just before the city’s liberation on September 7, 1944. “He was 17,” he says. “They sent him to Sachsenhausen, a concentration camp north of Berlin. He was there for the rest of the war until the camp was liberated by the Russians in April 1945. He was lucky to be young, otherwise, he might not have survived. But he came back as an old man. I never played football with my dad.”

Audrit and his older brother Michel – who would later join the Belgian Air Force, become its top officer and teach King Philippe to fly – would nonetheless “harass” their father with questions about the war. “I was hearing the story of Jean de Selys and his attack on the Gestapo HQ since I was a child. It’s almost my cultural landscape. I remember the first time I saw the building. It really meant something to me,” he says.

But Audrit was later astonished to discover that no biography had been written about de Selys. “It's strange when you consider the massive awareness around him and what he did. If you Google de Selys, you’ll find hundreds of results. He's the most famous Belgian military figure by far. Year after year, I hoped that I’d find the book I was waiting for. But I realised it wasn’t going to happen and I better do something about it myself. I invented a sort of artificial pressure – to get it done by the 80th anniversary of the raid this year. I was somehow pushed by an invisible hand, saying, ‘Hey, it's now or never.’”

Audrit, who divides his time between his family home in Uccle and work in the communication and advertising sector in Paris, paused his professional activities to spend two years researching and writing the book, the first he has published. “It’s been a huge endeavour. I feel like I’ve slept with Jean de Selys,” he laughs.

Audrit drew on the collections of the de Selys family: Jean had two older siblings, Monique and François (grandfather of Princess Delphine), as well as a younger brother, Edé.

As a student pilot at Odiham, 1941

De Selys’s brothers also distinguished themselves in the war and his sister was decorated for her service with the resistance. They have passed away but their children continue to treasure mementoes of their uncle’s life including a short wartime journal, photo albums and his RAF flying logbook. “Every single flight of Jean de Selys is recorded in the logbook, in his own handwriting. When you touch something like that the first time it’s emotional,” says Audrit.

But even with the family’s blessing (“They’re proud that someone took the time to finally deliver something that could be considered as the story,” he comments), Audrit underlines that he was determined to avoid a hagiography.

Dissolute youth

Audrit doesn’t gloss over de Selys’s somewhat dissolute youth. “He was a really lazy guy, mostly interested in doing nothing but riding horses and partying. But that only makes his raid even more extraordinary. Nobody in the world would have expected someone like him to become a hero.”

De Selys dropped out of school and university, working as a bank clerk for a time. His father Raymond, who was decorated by Belgium, France and Britain during World War I, encouraged his wayward son to enlist as a reserve officer in the Regiment of Guides, an illustrious cavalry unit.

When Germany invaded Belgium on May 10, 1940, De Selys was mobilised and transferred to the “groupe cycliste” of the 17th Infantry Division. As an officer, he escaped having to ride a bike and served instead with the headquarters staff. Nevertheless, he saw plenty of action during the 18-day campaign and received a citation for bravery before the capitulation.

De Selys was only 20km from the coast when Belgium surrendered on May 28. Two days later he and other Belgian officers boarded a boat in De Panne bound for Margate on the north coast of Kent. After a brief stopover in London, de Selys reached Tenby in South Wales, where Belgian military evacuees had been ordered to concentrate (see separate article).

“He discovers it’s a nightmare in Tenby,” says Audrit. “A lot of people not knowing what they're doing. With his connections, de Selys could have easily landed a job at a headquarters in London or in the Belgian Embassy, but then he hears a rumour about the Belgian army re-forming in France.”

Four days after arriving in Britain, de Selys is on a ship to Brest in Brittany with several hundred compatriots, determined not to give up the fight. But their mission fails against superior German forces. Most will spend the rest of the war in captivity.

De Selys, however, manages to get away. He reaches Montpellier and then Sète, where a cargo vessel takes him to Gibraltar. While some Belgians board ships for Britain, de Selys decides to go to Morocco instead. “He heads to the military flying school in Oujda. He has no intention of becoming a pilot – he just wants to help,” says Audrit. “But it’s a roller-coaster period. The situation feels like a disaster for him.”

Deciding to return to France, de Selys ends up in Marseille where he hears that his older brother François, who also escaped after the surrender, has been seriously injured near Pau. While out on a bike, he was hit by a truck, leaving him in a coma for 16 days. Jean rushes to be at his side.

His brother eventually recovered and returned to his family in Belgium. Jean, however, decided to stay. Many Belgians, mostly from an aristocratic background, are now living in the area. “It’s almost as if there’s no war going on. There’s this little Belgium, artificially recreated by the nobility around Pau. They all know each other and there are lots of parties. It’s a beautiful parenthesis in his life,” says Audrit.

At the same time, De Selys feels “lost” as he struggles to work out what he should do next. “I found evidence that indicates he even considered going to the Belgian Congo to rebuild there,” adds the author. “But, finally, after lots of zigs and zags, he decides to go back to Britain because it’s still fighting and there’s a chance it might overcome Germany.”

By the end of November 1940, de Selys returned to Gibraltar to find passage on a ship to Glasgow. He arrived in Scotland on December 16 and, two days later, enlisted in the Royal Air Force in London.

Breakthrough

Audrit is particularly proud to have uncovered details about de Selys’ “wanderings” after Belgium’s surrender. “There was really nothing known about this period of his life. I studied the archives and tried to connect dots, but it was all a bit of a black hole.”

A breakthrough came earlier this year when the newspaper La Libre Belgique published an article by Audrit about the planned biography. He was subsequently contacted by a reader who had a diary belonging to a relative who was in the south of France in summer 1940 and who had met de Selys there.

He was able to fill other gaps thanks to the memoirs of Albert Guérisse, alias Pat O’Leary, leader of the famous undercover network which smuggled Allied servicemen out of occupied France. “There's a beautiful picture of de Selys with Guérisse in a bombed-out building in De Panne. That’s where they meet. They’re together in Margate, in Brest, then in Sète where they embark on the cargo ship to Gibraltar.”

But perhaps the most significant discoveries in the book concern the raid on the Gestapo building itself. “There are an amazing amount of fanciful stories about it,” says Audrit. “There are mistakes, errors, even lies.”

He offers up four examples.

“It’s frequently claimed that the reason why de Selys attacked the Gestapo headquarters is that his father Raymond was arrested and tortured in the cellars. In some cases, it’s even said that he was killed by the Germans. Fake, fake, fake! Raymond was never arrested by the Germans, never tortured and died in 1966. From a storytelling point of view, the idea that the son wanted to avenge his father’s death is powerful. But it’s rubbish, unfortunately.”

Barely stopping for breath, Audrit continues: “The second big myth is that, when he attacked the building, de Selys killed an undercover MI5 agent who was wearing a German uniform. It’s claimed that in one of his pockets, they found a list containing the names of a Belgian resistance network. As a result, the entire network was arrested and executed or deported. So the ‘hero’ apparently made a huge mistake. Well, again, this is fake. None of this happened. A resistance network was discovered and disbanded – but this was five days before the raid.”

Audrit has a theory for why the story about the MI5 agent emerged. “I suspect the Germans themselves might have created this rumour. Remember, they were hugely humiliated by the raid. It would make sense for them to spread the word that they’d found the names of resistants after unmasking a spy among the victims.”

And the third myth?

The claim that de Selys was demoted by the Royal Air Force for carrying out an unauthorised mission.

“This only makes sense if you think they were really upset, but they gave him the Distinguished Flying Cross after the raid!” Audrit says. He discovered what really happened when he searched the military archives and found letters from his commander at No. 609 Squadron questioning de Selys’ ability as a flight leader. While De Selys had been promoted to oversee a flight during the summer of 1942, he was no longer a flight leader when the raid took place.

The 609 Squadron, 194, Jean de Selys Longchamps standing fifth from the left

“It was a nice surprise, a real ‘Aha!’ moment,” Audrit says. “To cut a long story short, de Selys was an exceptional pilot but a poor leader. In business nowadays, you’d say his leadership skills were questionable. As a pilot, he got better and better over time. But he was not interested at all in leading a team.”

The fourth misconception is that he was kicked out of No. 609 Squadron for disobeying orders when he carried out the raid.

Says Audrit: “De Selys asked for a green light for the attack but it never came. Having said that, he didn’t receive a formal red light either. Today we’d say he applied the popular wisdom ‘Better ask for forgiveness than permission’. But he certainly wasn’t asked to leave. He joined No. 609 Squadron in September 1941 and spent the bulk of his RAF career there. In March 1943, he decided to move to No.3 Squadron, which was headed by another Belgian, Léo de Soomer. So it wasn’t a punishment.”

It was to be a short engagement for de Selys.

The exact cause of the landing accident which resulted in his death at RAF Manston on August 16, 1943, remains a mystery.

“He was flying solo. That's partly why we don’t know exactly what happened. Was he hit by flak? Was his aircraft damaged? There was no emergency mayday call. He’d left at 1.35am and returned around three and a half hours later. As de Selys was preparing to land, the tail of his aircraft came away and the plane smashed into the ground. He was instantly killed,” says Audrit. De Selys, who was 31 at the time of his death, was laid to rest at the nearby Minster-in-Thanet cemetery.

Some 25 Typhoon planes were lost and 23 pilots killed during the war due to similar tail failures. “The designers never found any real solutions to the problem,” says Audrit. “The accident was probably half due to structural causes and half due to flak damage. But we’ll never know for sure.” By October 1945 the Typhoon was withdrawn from operational use.

Audrit is proud that he saw the project through. “I think we owe a debt to all these guys who sacrificed themselves for our freedom. We must not forget them. I'm not naive. I am pretty sure that only a small fraction of Belgium will read my book. Fine. Maybe some young minds will be among them and in 2043, when we celebrate the 100th anniversary of what de Selys did, at least someone will still be there to understand what happened.”

He also hopes the book – penned in French – will be translated into English soon. But he admits to one regret.

“It’s the only one, but it's a big one. It’s that I've been carrying the story and idea for the book for over 20 years. Had I started 20 years ago, I would have had the chance to talk to people who served with de Selys.”

But then in August, after the manuscript was complete, something extraordinary happened.

“I was in Kent at a commemoration for the 80th anniversary of de Selys’ death,” says Audrit. “I met a 98-year-old woman there and we started chatting. In 1943, she was 18. It turned out she’d spent the last evening before his death with Jean de Selys. It was the first time I’d spoken with someone who had been with him when he was alive. It was an amazing moment. I’ll never forget it.”

The dark side of Avenue Louise

The hated Gestapo and German security police, known as the Sipo-SD (Sicherheitspolizei-Sicherheitsdienst), requisitioned three buildings in Avenue Louise during the war – numbers 453, 347 and 510.

After the de Selys raid, they moved their centre of operations from 453, also known as Résidence Belvédère, to another apartment block at number 347.

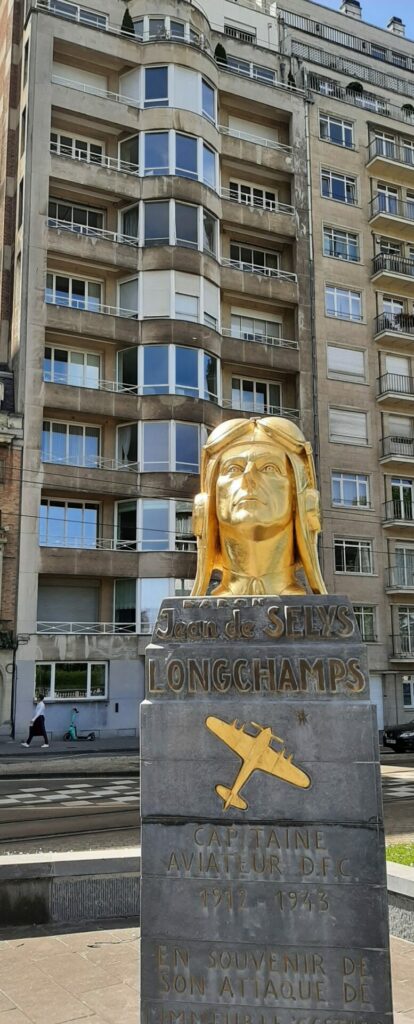

[caption id="attachment_902471" align="alignnone" width="414"] Ave Louise today, with bust of de Selys[/caption]

Ave Louise today, with bust of de Selys[/caption]

Prisoners including Jews, suspected members of the resistance and political opponents, mainly communists, were tortured in the cellars of the buildings. The prisoners left desperate inscriptions on the walls, which were subsequently painted over.

Owners and tenants in the buildings resisted moves for the basements to be conserved. However, following a report by the Royal Commission for Monuments and Sites the cellars at 453 and 347 received listed status from Brussels Capital Region in January 2016.

Another place of Nazi terror was 6 rue Traversière, occupied by the Geheime Feldpolizei (Secret Military Police). The building was later turned into a youth hostel.

Of all the buildings, the only external sign of their dark past is a plaque on the wall of 453 Avenue Louise recalling the de Selys raid.

[caption id="attachment_902470" align="alignnone" width="1024"] The plaque on the wall of 453 Ave Louise[/caption]

The plaque on the wall of 453 Ave Louise[/caption]