Livestock carriers are the most dangerous vessels in the world but are still permitted to load live animals in European ports for export to third countries, according to a new report by two NGOs.

The report, published last week by German NGO Animal Welfare Foundation (AWF) and French environmental NGO Robin des Bois, includes detailed data about the substandard state of the 64 vessels that currently are in traffic. Under current conditions, the two organisations call on the EU to stop livestock export by sea immediately.

The report was accompanied by a video showing disturbing images of loading of animals to the vessels and the conditions on-board.

As previously reported, the European Commission presented last December an animal welfare package to improve the rules in three different areas but it fell short of the more ambitious revision of the outdated legislation that it had committed to propose.

As regards live animal transport, the package included a number of new rules to better protect animals during transport. Export of live animals to non-EU countries will still be allowed under tightened rules. However, long distance travel by sea will not be limited. The new provisions are not enough to prevent the cruelty in sea transports, according to animal welfare NGOs.

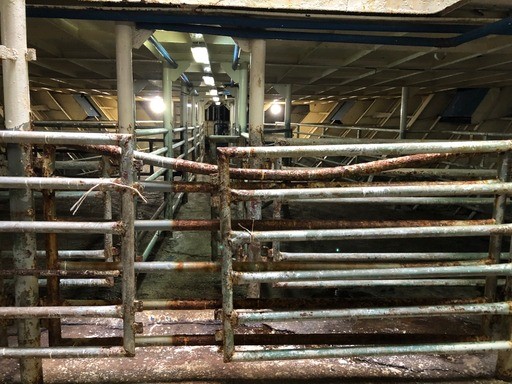

The report looks at the seaworthiness, safety, environmental compliance, and suitability for health and animal welfare of livestock carriers operating in the EU. The average livestock carrier is a 43-year-old vessel held together only “by rust and hope”. Almost all vessels were not built for carrying livestock and served as cargo ships until they were deemed not safe for their initial purpose.

Vessels under black flags allowed

Furthermore, nearly half of the EU-approved livestock carriers are flying the flag of a country listed as a ‘black flag’ by the Paris Memorandum of Understanding (an agreement between maritime authorities on port state control). This means that the vessels pose an extraordinarily high risk to maritime traffic, as well as to the lives of the animals and crew on board, and to the environment.

Loading of animals, credit: Animal Welfare Foundation

Disasters with livestock carriers are commonplace. High-risk vessels that are detained in ports due to deficiencies are normally banned to continue operating and scrapped but this seldom happens with livestock carriers. 15 out of the 17 vessels that were identified in a previous report in 2021 as high-risk vessels are still approved in the EU.

"It's been three years since the last joint report by AWF and Robin des Bois,” commented Iris Baumgärter of AWF and Charlotte Nithart of Robin des Bois. “Three years during which the suffering of animals on board of defective vessels has simply been accepted. EU legislation must finally confront the brutal reality of live animal transport by sea and take action.”

Why are vessels that were not considered seaworthy according to the previous report still in traffic? A Commission spokesperson replied that the approval of livestock vessels is a responsibility of the competent authorities in the member states, following official checks of compliance with requirements provided in a Council Regulation from 2005 on protection of animals during transport.

Vessels are approved for five years. “Despite better knowledge and information about deficiencies, the Commission and member states are not obliged to withdraw the approval or forbid the loading of animals on substandard ships sailing under black flags,” Iris Baumgärter, who contributed to the report, told The Brussels Times.

Does the Commission exercise effective supervision of the approvals and sea port controls of livestock carriers by the member states? The Commission replied that it carries out regularly audits of member states’ compliance systems to protect the welfare of animals during transport to third countries on livestock vessels.

When non-compliance with EU law is found, the Commission issues recommendations to the concerned member state and monitors corrective actions.

One of the key conclusions from the Commission own audits is that “the way in which member states carry out inspections on loading and unloading of animals in accordance with the regulation is generally not sufficient to minimise the risk to animal welfare inherent in that type of transport”.

A Commission spokesperson told The Brussels Times that the Commission takes very seriously the findings in the NGO report and referred to new rules on transport of live animals by sea that were adopted last year. According to the spokesperson, the rules have been or will be reinforced.

Inside livestock vessel, credit: Animal Welfare Foundation

Will new rules be sufficient?

A proposal for a new regulation on the protection of animals during transport was adopted by the Commission on 7 December 2023, based on experience from the implementation of the 2005 regulation, the results of the audits and other inputs. The proposal is open to comments on the “Have your say” portal until next Friday (12 April) and can be downloaded from the portal.

The Commission also adopted on 17 February 2023 a Delegated Regulation that already have entered into force as regards rules for the performance of controls to verify compliance with animal welfare requirements for the transport of animals by livestock vessels. An Implementing Regulation of the same date lays down rules on the recording and sharing of information of the controls.

This is a very technical area that requires different experts to inspect the construction and maintenance of live-stock vessels and assess if they are fit for transporting live animals, commented Iris Baumgärter. The Implementing Regulation requires expert teams for the approval of vessels but does not ban the approval of vessels under substandard flags.

“The proposal to revise the 2005 regulation is expected to exclude at least vessels under black flags from approval but it still has to pass the political process. What will happen with vessels under black flags?”

Currently, the inspections of livestock vessels are mostly done by veterinarians. A 2020 network document on livestock vessels proposed that the inspecting teams should consist of official veterinarians and maritime experts. However, the document, labelled as a guidance to the member states, was not a legally binding document but a best practice recommendation.

The Commission admits that veterinary competency alone is not sufficient to check the functioning of livestock vessels that may have an impact on the welfare of the animals being transported. This is now covered in the Implementing Regulation (article 9) and should lead to that only white flagged vessels will be approved.

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times