Lockdown measures taken across the world in response to the Covid-19 pandemic caused seismic noise across the planet to go down by 50%, according to research published in the journal Science.

The research was led by Dr. Thomas Lecocq and Dr Koen Van Noten of the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Uccle in Brussels, and involved collecting data from seismic monitoring stations across the world. In the end, the project involved 76 authors from 66 institutions in 27 countries.

The term seismic noise refers to the vibrations caused by natural movements in the Earth’s crust, known as seismic waves. These are measured by hundreds of monitoring stations across the world.

Researchers in seismology are mainly interested in seismic waves relating to earthquakes, but their calculations are polluted by what is known as ‘buzz’ – high-frequency vibrations caused by human activity on the surface of the planet, from driving cars to construction work.

Each type of buzz has its own seismic signature, and buzz is stronger in the daytime, and lighter at weekends.

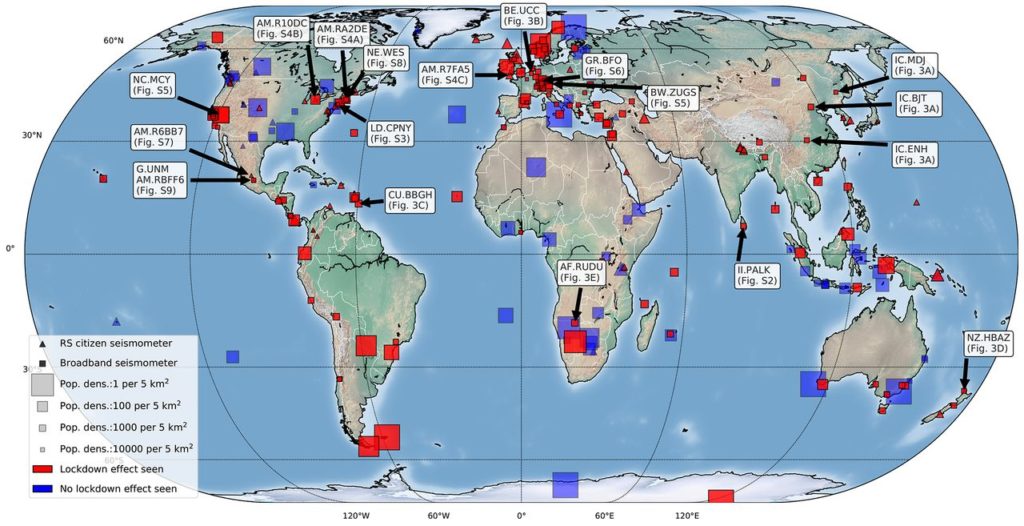

What Lecocq and Van Noten found, which the international cooperation confirmed, was that lockdown measures taken in response to the pandemic led to a substantial reduction in buzz at the 300 or so seismic monitoring stations across the world (some of which are shown on the map).

It even became possible to read the seismic data record for the period and see the waves of reduced buzz begin in China and move across the world to Italy and beyond, becoming more or less global, and matching the spread of the virus.

The resulting quiet period, the Observatory says, is “the longest and most prominent global anthropogenic seismic noise reduction on record”.

The effect, moreover, was recorded at depths of hundreds of metres, as well as in remote areas as well as urban centres.

In Brussels, meanwhile, not only was seismic buzz reduced during lockdown. Also contributing to the study was Bruxelles Environnement, the region’s environmental agency, which provided audible data gathered from microphones installed in the city. And the reduction in actual audible noise recorded during lockdown correlated with the reduction in seismic noise.

A communique from the Observatory concludes, “With growing urbanisation and increasing populations globally, more people will be living in geologically hazardous areas. Therefore it will become more important than ever to characterise the anthropogenic noise humans cause, so that seismologists can better listen to the Earth, especially in cities, and monitor the ground movements beneath our feet.”

Alan Hope

The Brussels Times