In the run-up to Congo’s independence from its Belgian colonisers in 1960, the Belgian state arranged to bring everything that was Belgian back to Europe, including children born to a black African mother and a white Belgian father.

These so-called ‘métis’ children were declared property of the Belgian state and forcibly taken from their mothers to be put on a plane to Belgium, where they often ended up in orphanages or foster families.

Métis children are the children that were born in Congo and Ruanda-Urundi under Belgian rule. They were sometimes the result of love between a colonial settler and a native woman, but more often the product of the colonisers’ abuse of power. In older official documents and newspapers, métis children were often called ‘half-bloods’, referring to only half of their blood being European, or ‘mulattos’, which has its origin in the Latin word mulus, the bastard offspring of a horse and a donkey.

Not only do both these words carry very pejorative connotations, but they also only refer to the children’s mixed skin colour. The word métis, however, carries no negative undertones and also refers to the children’s colonial background. It is the word Congolese people with a white parent or grandparent now call themselves.

Children of the sin

The exact number of métis children in Belgium is unknown. According to the Save institute in Rwanda, they hosted 124 children when they were brought to Belgium, and 881 other children were taken from Ruanda-Urundi and the region around the Kivu lake. However, some files have next to no information about what happened to them, or if they even came to Belgium in the first place. These files only exist if the children were officially registered with the Belgian colonial authorities when they were born, which usually did not happen, meaning the number of métis children is likely to be much higher.

Relations between white and black people were not only disapproved of, but often sanctioned, and one of the reasons many Belgian fathers did not acknowledge their mixed-race children. Even under colonial rule in Congo and Ruanda-Urundi, mixed-race métis children were not tolerated. Black people were made to live completely separate from their white colonisers, and ‘half-blood’ children were the visible proof of the disrupted colonial order and had to be taken out of sight.

Mothers were pressured to sign documents in a language they did not understand to give away their ‘children of the sin’ to institutions like the Witte Zusters (White Sisters) in one of the first Catholic missions in Save, Rwanda.

“When I was six years old, I was taken to the school in Save. I only have a few memories of my mother and father,” Jaak Albert, who is 67-years-old and the son of a white Belgian father and a native Tutsi woman in Rwanda, told The Brussels Times. Jaak was one of the first métis children taken to Belgium before the decolonisation.

“I was too dark-skinned to be allowed to go to one of the white schools, but because I was mixed-race, the ‘fully’ black children often bullied me. When I was seven, I was put on a plane with the other children in Save and taken to Villa Bambino, an orphanage in Belgium. I have lived with several foster families, but I finally found a nice working-class family in Antwerp where I had a nice youth. Many of us did not. I was lucky,” he added.

Once in Belgium, the children were often not recognised as official Belgian citizens, and were de facto stateless. They did not have a birth certificate, often not even a last name, and had to deal with many administrative problems later on in life.

Clean slate

“Under the pretext of the violent incidents associated with Congo's independence in 1960, all the métis children that were held in the orphanage in Save and elsewhere were collected in Usumbura (the former capital of Burundi, now called Bujumbura), with the support of the Belgian authorities. Without informing our mothers, we were flown to Belgium by plane,” reads the website of miXed2020, an association for and by métis children to help each other find family and peers.

This ‘evacuation’, which was essentially an abduction of the métis children, allowed the Belgian authorities and charities to systemically label them as orphans to be adopted or placed in foster homes, regardless of whether or not their mothers in Congo or their fathers in Belgium were still alive.

After the children had been brought to Belgium, they were placed in adoption or foster families.

“People were convinced that a new start with a clean slate would be better for the children. However, nowadays, pedagogues and psychologists agree that it is much better for adopted and placed children to have the opportunity to find out what their personal trajectory and history is. The ‘clean break’ policy that was applied by the Belgian state in the 50s and 60s is now considered traumatic,” said Sarah Heynssens, a historian at the National Archives of Belgium and the Ghent University.

“Being a person who does not know where they come from, does not know why they were not raised by their parents, and grew up with the idea that their parents abandoned them even though they did not, is a difficult challenge. The ‘clean break’ policy had a lot of negative effects on the psychological well-being of these people,” she added, as the métis children were not only left in the dark about their personal history, but their shared cultural heritage as well.

“I have looked for my biological parents my entire life,” said Albert. “However, as I officially did not have a family name, it was incredibly difficult to find any useful information,” he added. His first name, ‘Jaak’, is officially spelled the French way, ‘Jacques’, as it was given to him by the Belgian French-speaking authorities in Congo. Even though it is still spelled ‘Jacques’ on official documents, he prefers to use the Dutch spelling whenever he can.

Sorry is a start

Associations of métis children, like MiXed2020 and Métis de Belgique/Metissen van België, have been asking the Belgian state to acknowledge their suffering, and take action for reparations. “We have studied, found a job, built our lives. Some were surrounded, educated, followed up on better than others. Many, unfortunately, have suffered greatly,” their website states.

In 2017, the Belgian Catholic Church officially apologised to the métis children for the part it played in separating them from their families. It asked all catholic institutions in Belgium, Africa and Rome to make available all documents that they have regarding the colonial period which could help the métis children find their parents or ancestry in Africa.

In April 2019, the then Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel officially apologised in Parliament for the treatment of the métis children under colonial rule and in Belgium, as well. After Michel’s apologies and the admittance of blame of the Belgian state, many métis children gathered all the files they had proving their abduction, lack of official documents and subsequent difficulties they experienced, to file a lawsuit, according to Albert.

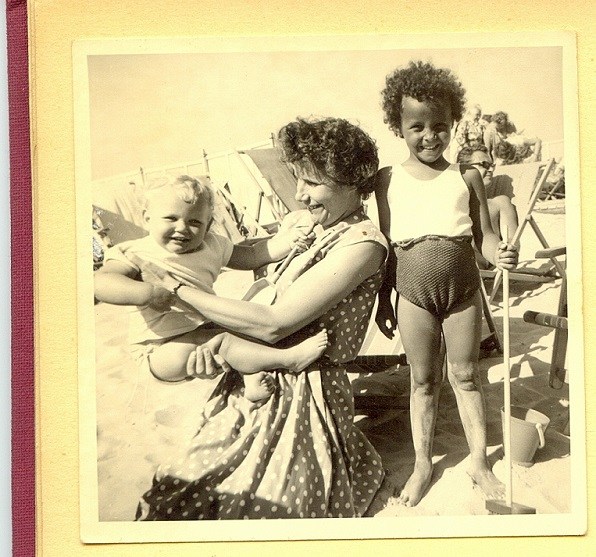

A photograph of one of the métis children with her adoptive family at the beach in Blankenberge in Belgium.

Heidi De Rudder, the Belgian daughter of a métis mother said the apologies were an important step in the process. “Sorry is not everything, but it is a start. My mother, now 70-years-old, was put on a plane from Congo to Belgium when she was ten. The Minister’s apology is important, but a little more cooperation from the government to find our families would be nice too,” she said. “Perhaps the government could make an explicit appeal to all the fathers, to make themselves known?” she added.

“A crucial collection of personal files of the métis children that were compiled by the colonial authorities in Belgian Congo and Ruanda-Urundi will be transferred in due course to the National Archives of Belgium. The files contain information about the fathers and mothers of mixed-heritage children. The intention was to evaluate whether or not the child was acknowledged by the European father. If so, the child could stay with him or his family. If not, it was forcibly taken from the mother and placed in one of the institutions like the one in Save,” Heynssens said.

However, the lists of names that exist are often not enough. The individual files of the métis children were made by colonial officers who only superficially informed themselves about the children. Many files only contain a first name, sometimes even only a nickname, according to Heynssens.

Duty

“In the Africa archives from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Brussels, I found two different files about me. The thinnest file was named ‘Jacques Albert’ and contained official documents from the public prosecutor, the village leader in Rwanda, and the Mother-Superior from the Institute for Mulattos. According to that file, my parents were unknown and I did not have a birth certificate. The name Albert, which is not actually a surname but more like a second first name, was given to me by Mother-Superior after I was baptised, right before the journey to Belgium,” said Albert.

“In the thicker file, labelled ‘Jacques’, I also found official files from the police, the public prosecutor and Mother-Superior. But there were also confidential documents like proofs of payment from my father, correspondence with the savings fund in Congo and Ruanda-Urundi, letters from my father, and the identity of both my parents,” he said. “So many pieces of the puzzle came together. All my unanswered questions were finally answered. I even discovered that I had a brother, who I met for the first time in November 2015, after not knowing he existed for 63 years,” Albert added.

“It is the government’s duty to open up these sources, make them available for research, and make them accessible for everyone who is directly involved. However, almost 60 years after the decolonisation, this has still not happened, which leaves a great part of the archives unable to be consulted,” said Heynssens.

“Hopefully our lawsuit will change something. We will know the outcome by the end of 2019. It has been almost 60 years, we have waited long enough,” Albert concluded.

By Maïthé Chini