After 100 hours of negotiations, the Special European Council reached a deal Tuesday morning on the recovery plan for Europe and the budget for 2021-2027.

EU leaders greeted the deal with relief and joy, describing it as a success for all 27 member states. Some of them vehemently opposed the amounts and the basic elements of the European Commission’s proposal. At the end, common sense prevailed and the tough negotiations ended in a compromise acceptable to all, though some programmes were cut and other decisions postponed.

Susi Dennison, director for European Power at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), told The Brussels Times that she was not expecting a deal to be reached this time around. “I underestimated the flexibility from both the frugal countries and French President Macron to get a deal.

How do you explain that the member states managed to reach a deal despite their differences of opinion before the summit?

“Everybody had to compromise – the frugal four or five on the principle and scale of borrowing to fund grants and on the governance structure, the southern states on the balance between loans and grants. EU leaders such as Macron who had hoped that budget rebates might be abolished after Brexit had also to swallow an increase in the rebate to the frugal states.”

“Even Hungary and Poland, who came off lightly on the rule of law conditionality, know that there was an explicit agreement that the German presidency would move forward with the article 7 procedure (to suspend certain rights). The Council will come back to the question of handling the rule of law, so this can only be done by kicking the can down the road.”

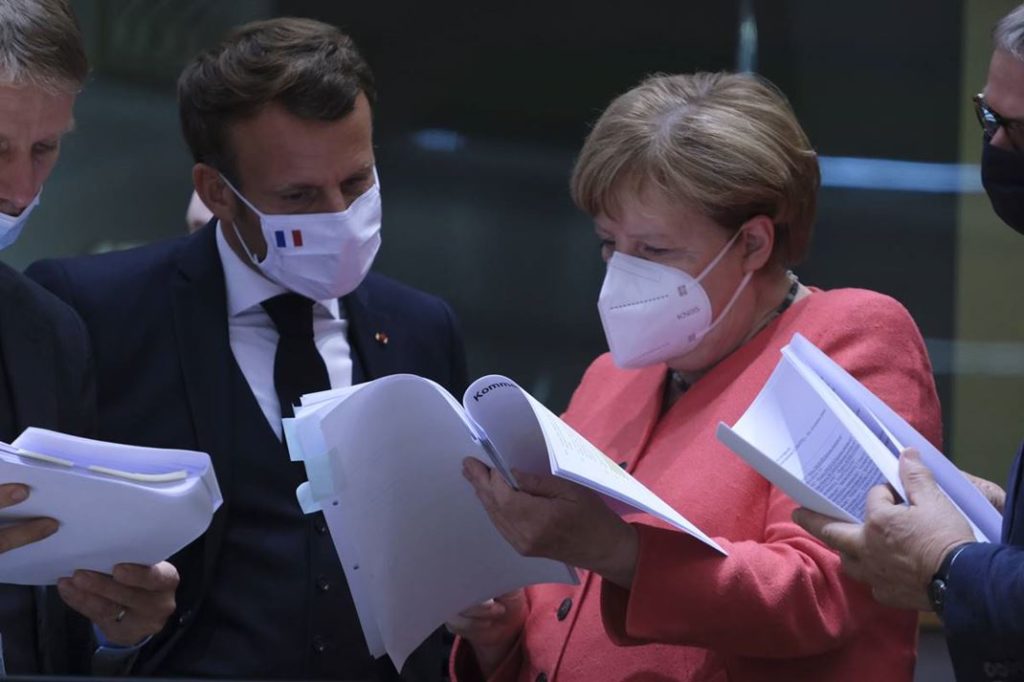

Council President Michel, with his experience of divided Belgian politics, played apparently a crucial role in bridging the gaps between the member states. “But I think that it was also critical that Macron and Merkel were working so closely together, determined to reach a deal, despite different hopes for the outcome.”

If you compare the outcome with the Commission's proposal, how close are they?

“The grant part of the recovery fund is lower than the Commission’s original proposal. The multiannual budget (MFF) is fairly close, but overall, there have been significant cuts in some key areas such as health and climate projects. It remains to be seen whether the deal will be satisfactory to the European Parliament and European voters since these areas – health and climate – are important to them.”

Satisfied Commission

How does the Commission itself interpret the outcome of the summit? A senior EU official, who talked yesterday (22 July) on the condition of anonymity, was overall satisfied with the result although it included both “light and shadows.”

The Commission is happy that the total amount of the recovery fund, €750 billion, was not touched and that the grant part, €390 billion, remained relatively “close” to what was proposed. Other positive results were that 30 % of the budget will be used to mainstream climate action and that new revenue sources will be introduced for repaying the loans that will borrowed on the capital markets.

He admitted that the Commission for the time being does not have the expertise for such financial operations but added that it has already started looking on how to build up the capacity.

On governance, the Commission fought back against those member states that wanted to introduce a right to block payments to non-reform minded countries. According to the decision, national recovery and resilience plans “shall be assessed by the Commission and approved by the Council, by qualified majority on a Commission proposal”.

Giving a single country the right to veto a decision was simply not feasible because it would not have been in line with the EU treaties, an EU official explained. Instead another procedure was adopted, the “stop-the-clock procedure” (article A19 in the decision). It allows a member state to request the European Council to refer the matter to the next Council. In the meantime, no decisions are taken.

This process shall, as a rule, not take longer than three months after the Commission has asked the Economic and Financial Committee for its opinion and after the next European Council has “exhaustively discussed the matter.” The Council will clarify the matter politically, the official explained, but the decision will be taken according to the committee method (“comitology”), applied by the Commission.

A hot potato in the Council discussions was the link between payments from the EU budget and the status of the rule of law, which is being undermined in some member states. “A regime of conditionality will be introduced,” according to the decision.

The Commission will propose measures in case of breaches for adoption by the Council by qualified majority. The Council “will revert rapidly to the matter” (article 23 in the annex).

Remaining issues

At their press conference on Tuesday morning, the EU leaders put up a brave face and stressed that the Council was committed to the importance of the “protection of the Union's financial interests” and “the respect of the rule of law” (article A24 and article 22 in the annex).

According to the official, EU leaders were themselves involved in drafting this text. The Commission is looking at the text right now and will propose what measures should be taken. He underlined the importance of article 24 in the annex, which invites the Commission to present measures to protect the EU budget against fraud and irregularities.

“It might seem a bit technical but will have a huge impact,” he said and referred to “measures to ensure the collection and comparability of information on the final beneficiaries of EU funding for the purposes of control and audit.” Tracing payments down to the “final beneficiary” is basic in the control of the structural funds but it was not explained how it will impact on the rule of law.

“You need to give us time to reflect on the exact nature of the provisions,” replied the chief spokesperson of the Commission to a question from The Brussels Times. “We are satisfied that there is this article 24 and believe that it is extremely important, together with the sentences about protecting the financial interests and the rule of law. This is a starting point for us.”

“There are a number of ways it could work out depending on where the issue is discussed – in a Council by qualified majority or at Heads of state level where unanimity is required,” Susi Dennison explained.

On the negative side, the Commission officials mentioned cuts in the financing of some of the new programmes, such as the Just Transition Facility and the health programme, EU4Health. The total funding to the facility, to help achieve the transition to climate-neutrality by 2050, was reduced by €20 billion, and EU4Health, a direct response to the pandemic, was reduced from €9.4 billion to €1.7 billion.

The EU officials downplayed the cuts, in particular the cut of the funding of the health programme, which was not explained. “We regret of course that our ambitious proposal was not followed entirely but are happy that the Council recognized the need for a new programme on health. We had nothing prior to the Council meeting, now the EU has a programme devoted to tackle the health crisis.”

The policy expert at ECFR explained that the cut was a concession to those member states, including the frugal ones, who were concerned that the programme is a step towards further EU integration. “Health isn’t a core EU competence so I suspect there was some push back against this part of the package as part of the discussion.”

Why rebates?

The Council increased the “rebates” or lump-sum corrections for Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and Sweden to compensate them for higher contributions to the EU budget after Brexit. Was it necessary to placate them for the deal?

“I think so,” she replied. “German, Swedish, Danish and French voters were not particularly favourable to the idea of sharing the financial burden within the EU. This was in no small part because – like all member states that ECFR surveyed at the height of the corona crisis– they felt that ultimately their country had had to fend for itself on the crisis.”

But unlike those in the South – who also felt alone –the frugal countries and Germany thought their national government handled the situation reasonably well. These states are still broadly in favour of more European co-operation after the crisis, like 63% of EU voters overall.

But they didn’t feel such an urgent national need for it as the southern states perhaps did – around 50% of Swedish and Danish voters, compared to 91% of Portuguese, 80% of Spaniards and 77% of Italians. The rebates agreed for the frugal states and Germany will be an important part of the narrative on why this deal works for them too.

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times