The Cyprus conflict is one of the world’s longest running international conflicts and has until now evaded a solution despite an UN-led peace process and EU support. The latest round of talks in June-July 2017 in Crans-Montana, Switzerland, between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots collapsed after the two sides were close accepting a framework for a solution presented by UN Secretary-General António Guterres. The elements were related to territory, political equality, property, equivalent treatment, and security and guarantees.

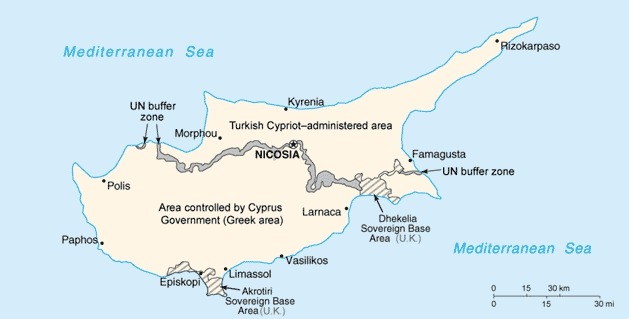

Since 1974, Cyprus has been divided into a Greek Cypriot part, the Republic of Cyprus, and a northern Turkish Cypriot part on about one-third of the island. In 1983 the northern part declared itself the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), which is only recognized by Turkey.

In his report (28 September 2017) on the talks in Crans-Montana, the UN Secretary-General wrote that the essence of a comprehensive settlement to the Cyprus problem was practically there. “It is therefore my firm belief that a historic opportunity was missed in Crans-Montana.”

How close they were a solution became clear in a recent hearing (7 November) on Cyprus in the European Parliament in Brussels organized by ALDE (Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe). For perhaps the first time in the parliament both sides were engaged in a dialogue on the so-called Guterres framework and the economic situation in the island.

Unsustainable status-quo

Spanish MEP Javier Nart, a former war correspondent turned politician in 2014 when he was elected to the parliament, moderated the discussion. He underlined the importance of listening to each-other but could not hide his disappointment with the presence of few Cypriot and other MEPs at the hearing.

“The current situation in Cyprus is far from ideal. One part (Northern Cyprus) is not a member of EU and the security of the other part (The Republic of Cyprus) is guaranteed by a trio of powers, one of which isn’t a member of EU (Turkey) and the other one (UK) is on its way of leaving EU,” he told the Brussel Times.

Javier Nart was referring to the Treaty of Guarantee of 1960 between the Republic of Cyprus, Greece, Turkey and the United Kingdom. It requires the other parties to guarantee the independence, territorial integrity and security of Cyprus.

“The Turkish community needed protection in 1974, when there was a coup attempt in Cyprus, and even before when it was discriminated but hardly today in an EU context. Turkish troops today are an anomaly and are guarding rather than protecting the Turkish community against an external threat that doesn’t exist any longer. The main guarantor today for Cyprus and the well-being of both communities is EU.”

In his view the ideal solution to the Cyprus issue would be a unified binational Cyprus, supported by the international community, but this is hardly realistic today. “The only solution is a federation of two constituent states which is far better than the situation today,” he explained and blamed the stalemate on politicians on both sides who do not dare to lead their constituencies to such a solution for the benefit of all Cyprus.

UN failure

In fact the conflict issues have been narrowed down to only a few percent of previous differences, judging by the negotiators from both sides. Alexander Downer, a former Australian foreign minister and UN envoy confirmed that the differences, after endless hours of negotiations, have been limited to about 5 %, at least as regards property and border issues.

“The failed negotiations so far were depressing although the Cyprus issue has reached a high level of maturity,” former Turkish Cypriot negotiator Özdil Nami said at the hearing.

“In Crans-Montana we failed to wrap up our negotiations and agree on how to respond to the Guterres package deal. The responses and final positions should have been given to Guterres for mediation and bridging any remaining gaps.” He did not exclude that UN had mismanaged the negotiation.

He believes in a more time-limited and result-oriented approach. “We saw that the Cyprus issue was about to be resolved in a matter of hours on the final night of the conference. We don’t need any longer months of negotiations – 3 months would be enough to prepare a new comprehensive settlement agreement.”

Andreas Mavroyiannis, his counterpart on the Greek Cypriot side, agreed that the last evening in Crans-Montana had been crucial. “We felt that it was our last chance and did put down in writing our acceptance of the Guterres framework.”

“In spite of all efforts the package approach unraveled because of Turkey’s refusal to accept the most fundamental element of the package which was the end of the guarantees,” he explained. “It refused also the idea of discussing the complete withdrawal of Turkish troops that currently occupy part of the territory of Cyprus.”

“We need to continue where we stopped. We can also get along with a new negotiating methodology with a time-horizon but without any deadline.”

The Guterres framework (see background box below) consist of six conflict issues or parameters and was apparently never presented in written form by the UN Secretary-General. The two sides wrote them down as they understood them. While they are claiming that they accepted the framework, they obviously needed to specify their positions.

Remaining issues

Are there still some important differences which are difficult to bridge?

“The issues outstanding are outlined in the Guterres framework,” replied Özdil Nami without specifying the main issues to be resolved. Once a new settlement agreement is reached, it should be voted upon in separate simultaneous referendums in both communities.

Andreas Mavroyiannis replied that the Greek Cypriot side “sticks to the idea of the package and all the elements including abolition of guarantees and withdrawal of troops. The Secretary-General needs to be convinced that if we resume talks we’ll have real chances of success where we failed last year.”

While the two sides have largely bridged their differences on five of the six parameters in the Guterres framework, they still disagree on security and guarantees. “The chapter, perhaps more than others, has been the subject of different, often conflicting, narratives and has generated seemingly irreconcilable positions,” Guterres wrote in his report.

For the time being Turkey does not seem ready to consider even a confidence-building minor withdrawal of troops. Speaking on 14 November at a ceremony marking the 35th anniversary of the establishment of TRNC, Turkish first vice president Fuat Oktay said that “Turkish Cyprus is one of the two founding and equal parts of the island and Turkey will not let Greek Cypriots ignore this fact.”

Javier Nart is clear on this point. “It’s understandable that the Turkish troops will not leave at once after a settlement but on the other hand it shouldn’t take too long time. A time horizon of 10 years during which the troops will be gradually reduced until they have been evacuated seems reasonable.”

“It could have already been done by now if both sides would have had the political will and courage to agree on a solution. But apparently there is still a lack of trust.”

A related issue is the fate of the British sovereign military bases in Cyprus as a British withdrawal from them might influence Turkey’s willingness to withdraw its troops. But according to the draft Brexit agreement, the UK will continue to keep them after a withdrawal from EU while the areas will be part of the EU customs union.

According to the EU chief spokesperson at yesterday’s press briefing in Brussels (20 November) this has been agreed with Cyprus that might have lost an opportunity to abolish the British occupation of these areas.

UN and EU roles

The peace process led by UN has reached a standstill. Is there room for upgrading EU’s role as an “active observer” to a more pro-active role as mediator? Should EU use its leverage on both sides? Not surprisingly the two sides see EUs role differently.

Özdil Nami replied that EU cannot be a mediator “since Greece and Southern Cyprus are both members of the European Union. Therefore EU cannot take an impartial stance under these circumstances.” Instead he proposes a reinforced role for UN, including arbitration as a last resort.

For the Greek Cypriot side “more EU involvement of the EU would have been ideal”. “Cyprus is a member of the EU and will continue to be a member after the settlement”, replied Andreas Mavroyiannis.

“Furthermore, the EU framework offers the best possible arrangements to most of the issues discussed in the negotiations and has been instrumental in shaping all convergences and progress achieved. It’s all about how to extend in practice the full implementation of the EU acquis throughout the island without touching upon EU primary law and without permanent derogations.”

MEP Javier Nart says to the Brussels Times that he doesn’t understand why EU cannot play a more active role in solving the conflict. “Cyprus is located in the Mediterranean Sea and is part of Europe. It’s in our own backyard. While EU is pretending that it can tell third countries how to solve their conflicts, it cannot solve an easier conflict inside the union.”

According to Kjartan Björnsson, head of the Cyprus settlement support unit of the EU, the peace process is led by UN and “owned by Cyprus” without much room for EU taking a more pro-active role. Instead he highlighted the financial aid that EU has allocated to the northern part of Cyprus – altogether above €500 million since 2006 - in funding infrastructure and supporting socio-economic development and civil society.

As regards the economy of the island representatives of the two chambers of commerce agreed that trade between the two parts will never reach its full potential without a political solution. In the meantime more can apparently be done in stimulating trade between the two parts and enabling trade between the EU and the northern part which is economically lagging behind.

| The Guterres framework for a solution of the Cyprus issue Guarantees: Current system with unilateral right of intervention by guarantee powers not sustainable and should be replaced by another system with supervision mechanism. Security: Significant reduction of foreign troops but timing and numbers remain to be agreed at the highest levels. Territory: Some adjustment of maps still required but within reach. Property: More prevalence will be given to disposed owners respectively current users depending on whether the area is subject to territorial adjustment or not. Equivalent treatment: Free movement of goods and persons with equitable treatment of Greek and Turkish nationals (some limited differences related to EU citizenship remain). Power-sharing: Rotating presidency on the basis of a 2:1 ratio (Greek-Cypriot president during two thirds of the mandate period) and positive vote from both communities when fundamental stakes for either community are involved. |

M.Apelblat

The Brussels Times