Students are showing up in front of the Royal Palace in Brussels. Their cheers are tempered by some protestors and boo’s from the public. One of the most important political prisoners in Nazi-Germany had been liberated by the US Army. Europe was freed. It’s May 7, 1945. A few hours earlier, fifty miles from Salzburg at Lake Wolfgang – deep into Austria, part of the Third Reich since the forced annexation in 1938 – two young boys and their sister must have heard about an impressive sight. An American tank crossed the road, only a few hundred meters away from the villa in Strobl, where they were held captive. One of their aides was able to escape and warn them.

When the Americans arrived, they seemed to be surprised. They had found the whereabouts of the captive royal family of Belgium, who had been deported from Brussels to Castle Hirschstein in Germany on 7 June 1944, one day after the allied landings in Normandy. The final stage of their imprisonment took place in a secret location as of 7 March 1945, where they feared for their lives.

They were found in Strobl guarded by about seventy Waffen-SS with watchdogs, surrounded by a high fence with barbed wire. Luckily, their resistance was minimal, seeing the Americans. The news that Germany had surrendered unconditionally the same day may have reached them in time. After lining up before their former captives and the American liberators, they made the Nazi salute and were quickly put on trucks and led away.

However, it would not be until 1950 that the King and his family could return to Belgium. The so-called Royal Question would dominate Belgian politics for five intense years and would shake the country to its core – and even threaten its future as a country.

Tragic beginnings

King Leopold III (1901-1983) rose to the throne on 23 February 1934 rather unexpectedly. His father, King Albert, had tragically died five days before. During one of his favourite escapist pastimes, he fatally fell in the Ardennes (Marche-les-dames), while mountaineering alone. The nation was shocked, grieving and hoping for a new exemplary royal pair to cling unto during the unstable 1930s.

Official portrait of King Leopold III and Queen Astrid, 1935. © Archives of the Royal Palace

When the King and his enigmatic Queen Astrid rose to the throne, they had to try to replace their immensely popular predecessors. Less than a year after the loss of his father, another tragedy befell the King. On 29 August 1935, the beloved and popular Queen Astrid died in a car crash on a day out in Küssnacht in Switzerland. The King was at the steering wheel and suffered only minor injuries. His wife died in his arms. Luckily, their three young children were not with them.

King Albert was widely seen as a Belgian hero after World War I (1914-1918): the King Knight. He had assumed military command – in accordance with the Belgian constitution – and chose to stay with his troops. Specifically, the Siege of Antwerp and the bloody Battle of the Yser – when his troops were entrenched for four years – gave him a prominent place in Belgian military history.

History has actually forgiven him for dismissing his Ministers of Defence and Foreign Affairs in order to maintain his course. King Albert saw his constitutional oath “to maintain the national independence and the integrity of the territory”, as a personal one. He had put aside the rule of “ministerial responsibility” and acted independently with his military staff.

King Albert’s wife Elisabeth was also idolised, as the Queen Nurse – for her efforts to assist hospitals during the war, – which boosted the morale of the troops and the Belgian people, and was also used in war propaganda. After the war, they were hailed as national heroes. Leopold saw his father’s autocratic, but highly successful, rule as an example.

A Parliamentary System in Crisis

Between 1934 and 1940, and to his dismay, Leopold saw the formation of at least nine national governments. He openly criticised political parties and politicians for the instability in the country and for selfishly pursuing a personal and narrow party agenda.

From 1936 on, out of fear for Nazi Germany, Belgium had been following and expanding a strict course of neutrality and independence, strongly supported and enacted by Leopold himself. Belgium pulled, with mutual consent, out of Franco-Belgian agreements. Could this keep the country out of an eventual war? However, it received much criticism from the French speaking part of the country. Belgium’s stance was not passive neutrality. Much effort was put into its defence system, including building four new forts east of Liège.

On 10 May 1940, German troops invaded Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxemburg and France, spearheaded by a seemingly unstoppable wave of tanks and planes. Which path would Leopold take? He must have wondered what his father would do, but did not hesitate. Leopold went to the military headquarters in Breendonk to command the Belgian army. He did this without any direct consent of his government.

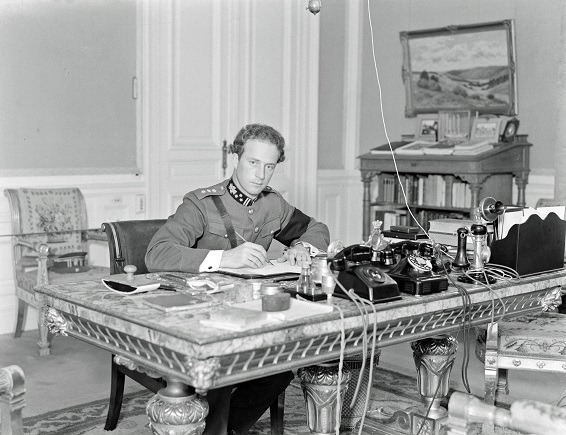

King Leopold III and Minster of Defense General Denis, 18 May 1940.

A sharp conflict with his Prime Minister Pierlot followed, when the defences were breached. The King expected Belgium to be completely crushed by Germany and refused to join the government in exile in France. By this, he violated the constitution.

He preferred to “stay with his troops and people, whatever the outcome, and share their fate.” He would not flee as other royal houses did. The Prime Minister maintained that Belgium was no longer “independent”, after having been invaded by Germany. Thus, it should morally side with the allied forces. The delegation left the King and joined the rest in exile in Limoges, France.

Royal surrender

After 18 days, on 28 May 1940, the King decided to surrender the army to prevent further bloodshed among his troops and people. Above all, on this last strip of unoccupied land, hundreds of thousands of fugitives were squeezing together. A final meeting with his Prime Minister could not change his mind; he refused to join his ministers for the later liberation of Belgium. For Leopold, the war was over.

He stayed and was captured the same day by the Germans. He was initially treated courteously, possibly helped by his German descent. His sister, Princess Marie-José, was married to the Italian crown prince – which was allied with Germany under Mussolini’s rule. He might also have thought that his relation with Italy would help play a political role in a Europe dominated by Nazi Germany.

More so, Leopold had held out for an impressive 18 days against the German aggressor and made a “wise decision” from their viewpoint. The Belgian government, exiled in France, stripped him of his constitutional powers since he was now captive and “unable to govern”. They could not appoint a regent, but decided they could rule as a body of government.

Leopold’s surrender was initially well received by his army and people; he had “prevented humanitarian disaster”. Luxembourg had already fallen after one day, the Netherlands after four. When France fell after six weeks in June 1940, the Belgian government fled to Britain.

After almost four years of privileged imprisonment in his castle in Laken, Leopold was deported to Germany on 7 June 1944, to “keep him out of allied hands”. It has even been rumoured that he insisted on this, although he and the Princess had written protest letters that they wanted to stay in Belgium.

When Belgium was liberated in September 1944, a memorandum was presented to the government. The King had prepared this text in his castle in Laken the year before, in case the country was eventually freed without his presence – possibly foreshadowing his deportation.

This so-called Political Testament sealed the King’s fate. In it, he was expecting public apologies from his ministers. He did not utter a single word about the liberation by the allied forces and the efforts of the resistance, possibly as a precaution should the text fall in German hands. He presented his authoritarian vision for a future society and even the virtues he expected of the youth: physically strong, noble, generous, and proud with a sense of social solidarity.

This prospect of a society imposed from the top must have brought back painful memories to many. He was clearly not dismissing all the undemocratic changes that had taken place under German rule or by other nations inspired by the New Order.

Controversial war role

During and after World War II, the decisions and actions of the King were overall ill received by the politicians and people of Belgium. The complex reactions depended also on the region.

The country had already, before its independence from the Netherlands in 1831, been made up of two large cultural communities. The northern part, Flanders (Vlaanderen) speaks Dutch, while the southern part Wallonia (Wallonie) is French speaking. Their differences in perception became all the more visible with the controversies surrounding Leopold, which were used by political parties and the press that had traditionally aligned for or against him.

Leopold had surrendered without the consent of his government. He had placed the Belgian policy of strict neutrality above a moral obligation to aid the allied armies or allow them to enter Belgium. He had only informed the King of Britain about his intentions three days before his surrender, but kept his intentions from the allied military command.

During the war, in November 1940, the King had personally visited Adolf Hitler in the Berghof in Berchtesgaden. After the war, this could easily be perceived as collaboration, by seemingly trying to make personal post-war agreements with the enemy. Would he be allowed to rule in a semi-autonomous state? Did he dream of a role as monarch in a bigger kingdom in the New Order?

“Your fate will be like ours” “King Leopold meets Hitler”

Leopold´s secretary noted that Hitler said that the smaller countries could later decide their own internal affairs, but that Leopold could not yet talk about independence openly. The whole story is still clouded in mystery.

Leopold had also tried to discuss the conditions of the prisoners of war and prevent a looming humanitarian disaster, for which he said he actually wanted to meet Hitler. However, he achieved rather little.

Overall, he thought that he had to protest very carefully against deportations and the suffering of his people. When he wrote to the Chairman of the Red Cross in December 1942 about the matter, he received a furious letter from Hitler in which he was threatened to be deported himself. Leopold only spoke and wrote about “prisoners of war” and “forced labourers”.

Did he include the Jewish citizens and residents in Belgium among his people? He has been criticised for not taking a clear position against anti-Semitism. Maybe he was influenced by his own anti-Semitic prejudices or of his advisors? That said, a few hundred Belgian Jews were saved after intervention by the King or the more active Queen Mother.

Although the scope of the Holocaust wouldn’t become fully known until after the war, the allied powers had already in December 1942 issued a declaration that condemned for the first time the Nazi “bestial policy of cold-blooded extermination” of the Jews and threatened to “ensure that those responsible for these crimes shall not escape retribution.” Was the King completely unaware of Nazi Germany’s war crimes and mass exterminations?

In December 1941, the Belgians were informed by Cardinal Van Roey, his most fervent supporter who also didn’t speak out against the Nazi atrocities, that the King had secretly married a commoner, Lilian Baels, almost two months earlier in a religious ceremony. The public was only informed one day after the civilian marriage. By this action, Leopold had actually broken Belgian law, since a civil marriage must precede a religious one.

It was now perceived by the broad public that the King was no longer a “lonely, suffering prisoner”. In fact, he seemed to be enjoying a lot of freedom. He was no longer selfless. “If you are so free that you can marry, why not do more for the people?” He alienated the people even further by stressing that his marriage was a strictly personal matter and that he forsook the title of queen for his wife and did not claim the throne for any of their possible offspring.

But, maybe the biggest witness against Leopold III is History itself: Germany did not win the war as Leopold had thought or hoped. In fact, one of the early allied successes in 1941 fed the hope of the Belgian people that continuing the battle was not fruitless and resulted in criticism of Leopold’s surrender.

End of the Royal Question

Since 1944, after the liberation of Belgium and the reinstating of the government, the King’s brother Charles was appointed as regent. He adhered to a strict ceremonial role.

When the King was freed, he had agreed that he would not yet return because of the political unrest and discussions concerning the role of the throne. In 1950, there was a peak in Leopoldist and anti-Leopoldist propaganda. The two blocks were each using one side of the story to blame the decisions of Leopold or the position of the government. In March, a people’s referendum took place.

Overall, 58% voted in favour of the King. However, the majority of these votes came from the Catholic Party. But more importantly, in Flanders, 78% said yes, in Brussels 48% and in Wallonia only 42%.

This would make the King acceptable to only one political party and in only one part of the country. He was no longer the “symbol of national unity”. Parliament allowed his return on 21 June 1950. He had been imprisoned in different conditions and exiled for almost 10 years. Violent and deadly protests broke out in the streets. The country seemed to be at the brink of civil war.

To preserve the monarchy, the King had no other choice but to ask Parliament, on August 11, to hand over his royal prerogatives to his oldest son, Prince Baudouin. The situation started to calm down. The next year, on 16 June 1951, he abdicated the throne and the crown prince now took his constitutional oath, as King Baudouin (1951-1993).

Leopold III signs abdication of throne on 16 June 1951 following a Belgian referendum.

Leopold moved out of the royal castle to live in Castle Argentueil in Waterloo in 1960, away from the new King, to fend off criticism of continuing influence. He kept silence and passed away in September 1983. He was laid to rest at the Royal Crypt of Laken, among past Belgian kings.

With his death, the Belgian historiography about his reign and the attendant controversies started fully. It was relived in 2001, during the anniversary of his 100th birthday, when his wife, Princess Lilian, published a book that Leopold had finished shortly before his death, containing important letters and the full text of the Political Testament.

He still did not mention the Holocaust or other persecuted minorities. Also, it was clear that he had barely changed his opinions and his abdication looked like the right thing to do. He wrote, in his typical way, that he regretted that he did not keep a minister at his side, “so there would not have been any problem.”

Uniting or Dividing Belgium

King Leopold III desired stronger rule from the top during the times of political and economic instability during his reign. It is rather ironic that his fate was ultimately decided by a direct, democratic vote in: a referendum.

The King of Belgium is historically seen as a factor of unity, even of continuity, over any crises and the coming and going of politicians. However, the war and Leopold’s actions made differences between Flanders and Wallonia painfully visible – even when he was trying to hold the country together. It must be said, however, that the line between history, anti-Leopold and anti-Belgium propaganda is sometimes very thin.

It should be noted that the King’s official title is “King of the Belgians”. The throne actually belongs to the people and is granted to the new King when swearing his constitutional oath before Parliament. Therefore, the power remains with the Belgian people to take it back, as happened with Leopold III.

Since regent Charles, King Baudouin (1951-1993) and King Albert II (1993-2013), the current King Philippe, the expectation was to act mostly ceremonially, consulting or advising freely but neither acting nor decreeing anything without the signature of a minister. It is a rule that is better followed today and closely watched in the press.

As a result of this history, from 1970 on, unitary Belgium came to an end and the process of federalisation was set in motion. There are no more national parties in Belgium. Gradually, the communities gathered more autonomy, which eventually led to the creation of the seven “governments” that run the country today.