The opening day of a landmark trial in Belgium saw a Rwandan man brought to justice for the first time for the "unspeakable" acts he allegedly committed during the brutal 1994 genocide in his country.

Fabien Neretse, a former top Rwandan official —who, at 71, is now grey-haired and walked into court assisted with a cane— stands accused of genocide, war crimes and of co-authoring 13 murders, including that of Belgian citizen Claire Beckers, her Rwandan-Tutsi husband, Isaïe Bucyana, and their 18-year-old daughter, Katia.

Neretse is also indicted with three attempted murders as well as with being responsible for an "incalculable" number of deaths for his alleged role in creating, training and financing a local branch of the Interahamwe armed militia who brutalised and massacred between 800,000 and a million Rwandans, mostly members of the Tutsi ethnic group, from 7 April to mid-July 1994.

"You will be confronted with the unspeakable, you will hear stories of horror," said Michèle Hirsch, the attorney of Becker's sister. "Genocide will be brought back into our present — the unspeakable will enter this room."

More than 25 years after the facts, Belgium is the first country to succeed in bringing Neretse before a court of justice after he fled Rwanda, where he was sentenced to life in prison in absentia, to ultimately settle in France, where he changed his name and lived for years as a political refugee.

Federal prosecutor Arnaud d'Oultremont cited witness accounts recounting how Neretse, a member of the government-backed Hutu ethnic group, exerted his influence and standing as a prominent and respected figure in his hometown of Mataba to support and buttress the Interahamwe militia in their genocidal campaigns in the village.

"Neretse is said to have been actively involved in the genocidal logic that sought the destruction and massacre of the Tutsi ethnic group," d'Oultremont said at the hearing, adding that the defendant in Mataba is said to have used a local school he founded to "actively contribute to the creation, organisation, training and armament of the young village recruits of the militia."

Related News

"The accused ordered the killing of Tutsis in the region. One witness confirmed that the militia he created had the mission of hunting out [Tutsi] enemies during the day," the federal prosecutor said, citing several witnesses as saying that the militias were effectively headquartered in the school.

Eleven of the murders he is accused of are those of his former neighbours in the capital Kigali, who were killed in a shooting which saw three people —two of them teenagers at the time— survive by playing dead among the corpses.

His other two alleged victims, Anastase Nzamwita and Joseph Mpendwazi, were killed in the vicinity of Mataba. Both are said to have been captured by local Interahamwe militia members led by Neretse, with the latter's body never found.

In his opening statements, d'Oultremont traced Neretse's ascendance to political prominence, citing his engagement with the Mataba community as a source of respect among local residents, and describing how he amassed a personal fortune and entertained close-knit connections with key political and pro-Hutu figures, particularly in Mataba.

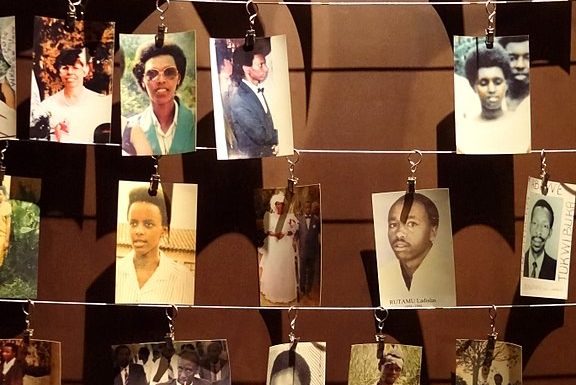

Photographs of Genocide Victims in a Genocide Memorial Centre in Kigali, Rwanda. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Hearing marred with 'diametrically opposed' stories

The first day of trial, which marks the first time a Belgian court tries a defendant accused of genocide, was marred by contrasting and at times contradictory assertions from both sides, with the defence challenging the prosecution's findings and accusations as "not credible."

Readings of conflicting witness accounts highlighted the prosecution's challenging task of proving not only Neretse's culpability, but also that his actions were motivated by a conscious intention of eradicating the Tutsi people, in a genocide which both the defence and the prosecution said was the result of ethnic animosities actively fuelled by Belgium's colonial occupation of the country.

Neretse and his house employee —a man named as Emmanuel, whose very existence is contested by the defence— are accused of denouncing the escape of his Tutsi neighbours in Kigali: the Beckers-Bucyana family and their neighbours, the Sissis and the Gakwayas.

As they attempted to escape their homes to reach a UN Blue Helmets base, the three families were stopped and summarily executed by the military and Interahamwe militias. "When the military opened fire, Claire Beckers was the first to crumble," d'Oultremont said, citing a witness.

But, an hours-long address to jurors saw Neretse's legal team slam the prosecution's accusations as vague, insufficiently precise and even contradictory.

"An innocent man appears in front of you," Neretse's lawyer Jean Flamme said in his address to the jury, telling them: "Your task will be difficult and will require the courage of not letting yourselves be influenced by national and international public opinion."

Neretse, now 71, is accused of playing a central role in an "incalculable" number of killings, including that of a Belgian-Rwandan family. Credit: Belga

Flamme issued scathing criticism of the case brought forward by the prosecution—which he called "shocking" in its lack of objectivity— saying the accounts of their witnesses were "not credible" and further accusing the court of failing to take the necessary measures to bring forth a key witness for the defence — the son of the accused.

"[Neretse's son] does not dare to come to the hearings, fearing reprisals in Kigali," Flamme said, noting that "nothing had been offered in ways of protection for this witness — fact of extreme gravity in a trial of this magnitude."

Neretse's appearance before the court on Thursday is the result of one Belgian woman's years-long quest for justice over the murder of her sister, her brother-in-law and her niece.

A complaint lodged in 1994 by Martine Beckers over the execution of her family in Kigali paved the way for Belgian prosecutors to lead a years-long investigation and build their case against Neretse, who denies all accusations made against him.

Via the principle of universal jurisdiction inscribed in Belgian law, several civil plaintiffs followed the prosecution's indictments over the slew of crimes Neretse will be made to respond to throughout the trial.

"The [Rwandan] genocide carries on to this day. And if it lasts still, it's in part because those responsible will not admit to it; almost none of them have asked for the forgiveness of the victims," a plaintiff's attorney said, adding: "The denial of genocide can be considered as a component of the crime."

"Mr. Neretse's victims have waited 25 years for this trial, it has taken years to find his trace through an assumed name in France," he added.

The trial is expected to last between four to six weeks and to rely heavily on the oral testimonies of a host of witnesses, some of which will be flown in from Rwanda.

The jury is set to listen to the testimony of Neretse on Friday, with witness accounts expected to be heard in court from next week.

Gabriela Galindo

The Brussels Times