The last person in Nabil Aniss’ family to wear the Haïk (حايك) was his grandmother, born in Morocco’s Atlas Mountains. The Moroccan Haïk is a multifunctional wool textile and a defining feature of Berber material culture. The garment could be used as a blanket, draped around the shoulders like a shawl or even rolled out on the ground as a carpet for weary limbs.

As Morocco urbanised, more and more mountain communities left their sharp-peaked villages for shiny cities and modern lives. The Haïks, too thick for the city heat and too woolly for contemporary fashion, were left behind. Today, Aniss cannot even find pictures of his grandmother wearing the Haïk, though the idea of the thick, blanket-like garment is ever present in his family’s consciousness – even more so now that Aniss has breathed new life into its memory.

Aniss moved from Morocco to Brussels to study at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB) in 2009 and stayed after falling in love with the Belgian capital. He worked in creative advertising agencies before becoming a full-time artist three years ago.

His main subject is determinism, and his art explores how we can break away from our so-called destinies. “I moved from a working-class Moroccan family into the Brussels bourgeoisie, which created a personal tension,” he says. “I wanted to understand why some people can change classes while others can’t.”

He began with physical installations and print, transitioned to abstract photography and language, and in the past year has dedicated himself to sound and film installation.

Bridging the gap

When he was invited to take part in For The Now’s Binôme, a Belgian design exchange platform, and partnered with Flemish designer An Gillis to create a physical art object that could bridge the gap between their diverse artistic and cultural backgrounds, the first challenge was just that: creating an object.

Aniss had shed his artistic interest in physical objects years ago. Gillis, on the other hand, was more grounded in the physicality of things. Though she, too, did not have an artistic background, she’d always loved the tactile nature of materials and making things with her hands. After studying and working in the field of economics, she went back to school to learn about interior architecture.

But faced with fast furniture design concepts, Gillis began asking herself some difficult questions. “We buy cheaply, we throw away, and we have no personal feeling for our objects,” she says. Out of this came a challenge: how to create objects that are imbued with value, that are treasured, that are passed on as family heirlooms?

The search for an answer led Gillis to the one thing that people continue to identify with: local history. She created objects and installations that narrate local history, personal histories – and make them think twice before throwing away.

When For The Now partnered Gillis with Aniss in the Binôme project, they were just told to create something together. “The biggest struggle was that there was no brief,” Aniss recalls.

Bridging differences was the entire point of the project – and to both Aniss and Gillis’ relief, they found common ground. “From the first time I saw him, I knew it would work,” Gillis says. Their work ethic was especially compatible. “Neither of us are free-spirit artists drinking all night,” she laughs. And soon, they landed on an idea: that which is hidden.

Haïk-barcode fusion

“The hidden” is a concept that they both related to in their own artistic journeys. Power dynamics in societies, and the connection that ties us to material objects are both things that are felt and not seen. And things that are felt are rarely given the same amount of credit as those that are seen. Thus they remain hidden.

But the idea still lacked an object – until Aniss thought of the Haïk, which had once been so important to his Berber ancestors. When he showed Gillis a picture of it, her reaction was immediate. “Yes. This is it,” she told him.

They identified a common visual element of the Haïk that was also often reflected in their own artworks: stripes. A simple pattern that is perhaps as old as design itself, and yet persists today not just as decoration, but also as a contemporary and practical tool: the barcode.

The final designs

This fusion between the Haïk and the barcode created a new artistic language to tell the story of lost material heritage and the dangers of modern throwaway culture.

The Haïk also reminded Gillis of medieval tapestries, an art that Flanders came to dominate. These textiles were handmade from wool and depicted contemporary scenes from history – a sort of ancient barcode, if you will.

So, how did Aniss and Gillis make the tapestry? They stuck to the ancient traditional material from both cultures – wool – and sourced it locally in Belgium, an endeavour that would unknowingly propel them into an industry that had also suffered from humanity’s fickle relationship to material goods.

Aniss quickly painted a deconstructed version of a barcode, but turning this visual into a Haïk-like textile woven out of Belgian wool would turn out to be much more difficult than expected, despite the hundreds of thousands of sheep that are kept in Belgium (110,115,000 as of 2020). So they turned to textile designer and Belgian wool connoisseur Céline Lambrechts.

A Vanished industry

Lambrechts was a natural mentor. Originally from the town of Lier (whose locals are nicknamed “de Schepekoppen” meaning “sheep heads”) she grew up around sheep and wool, and now is determined to revive the sector.

For a region once known as the wool capital of Europe, the fact that Belgium exported €14 million in wool in 2022 but also imported €8 million in foreign wool that same year (primarily from New Zealand, the UK and Germany) is frankly astonishing. “That’s why in our country that whole industry vanished in the last century,” Lambrechts says.

The reason for this shift? Buyers prefer softer and cheaper wool from places like New Zealand and Australia, valuing this over the ancient artisanal culture of their country, Lambrechts says. As Gillis would say, they no longer identify themselves with their material heritage.

Despite the challenge of working with a product that Belgium is no longer equipped to process, Lambrechts was committed to using local materials and being involved in every step of the creation process: from washing the wool to spinning the yarn to weaving the final product.

Lambrechts joined a small but growing community of people trying to reduce wool waste and reignite this ancient industry. While Lambrechts uses it to create textiles, some companies have tried using it as isolation material in construction, and some gardeners even experiment with wool as an alternative to mulch.

When Gillis called Lambrechts, the prospects were bleak. Most Belgian wool is treated as waste material – and the rest is processed overseas.

Gillis and her creations

But Lambrechts made some prototypes for Aniss and Gillis, and over time the artist duo found more local experts that ultimately made the creation of the Haïk possible.

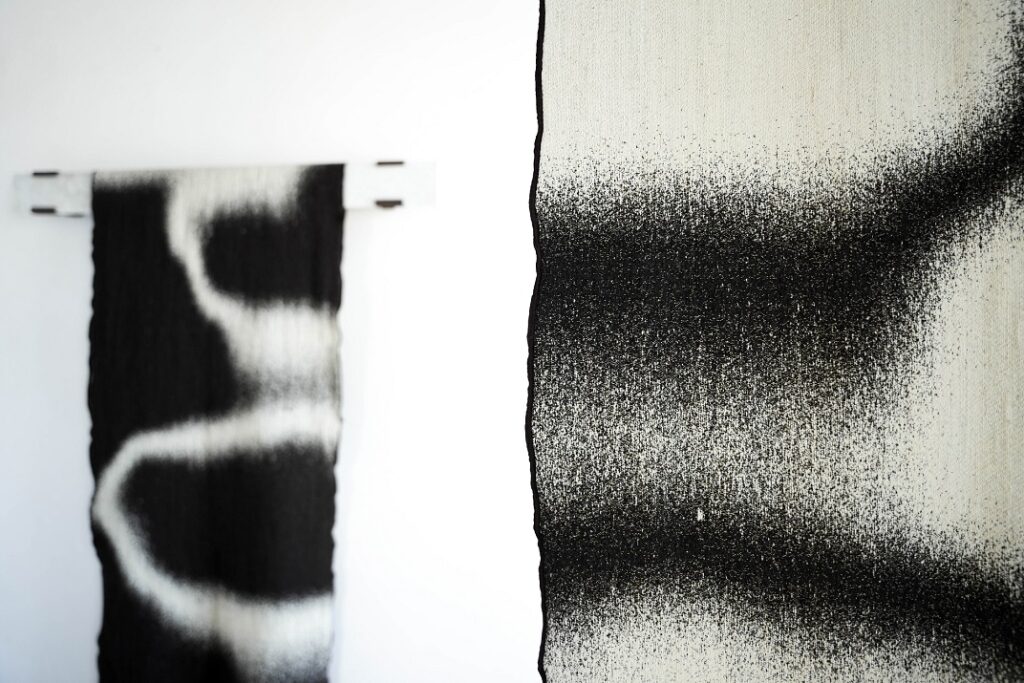

Frédérique Bagoly, owner and creator of the natural fibre spinning mill in Namur called La Filature de Hibou, sourced local wool and spun it into yarn. Then Marie-Anne van der Plaetsen from the weaving company B&T Textilia tested the yarn on their industrial machines and created the final product: two tapestries (that can be hung on a wall or worn as a garment) and a mat with a cushion, also stuffed with Belgian wool.

New language

Aniss and Gillis’ installation, first exhibited last September at Gare Maritime during Brussels Design September, underlines the clash between ancient material heritage and modern consumer habits. It also raises a question: what do we do with this impractical yet important tradition?

One possible answer is recommitting to using locally sourced materials, as Lambrechts does. Aniss and Gillis want to prove that though difficult, creating wool products from start to finish in Belgium is not impossible. They hope their work inspires designers and companies to work with local materials – to fight against a deterministic future and reconnect with their local roots, as Aniss and Gillis might say.

“That's one of the stories we wanted to tell the other designers. You can do this in Belgium, you just have to commit some effort and work with companies that have a lot of pride in what they do,” Gillies explains.

On the other hand, the artists say that the conservation of history is ultimately a museum’s responsibility, and that artists who try to take this colossal task upon themselves tend to resort to a nostalgic and often imprecise reminiscent lens.

Gillis, however, does think that artists should express collective heritage with a contemporary touch to remind people of their past and consider how to integrate that knowledge into their present. “It’s a way to keep telling our history in different ways,” she says.

But for now, they hope their work makes people question themselves. “The meaning of art is to present reality from another point of view and make people think, ‘I see what they want to say, but I never thought about it this way.’ It’s about creating a new language,” Aniss says.