Yes, I did write the headline for this article and no, it isn’t the first of April.

It is a fact that Belgium was one of the early pioneers not only of the automotive industry but also of the electric car industry long before net zero had become the imperative that it is today. Add on top of this the fact that a Belgian-designed and manufactured electric vehicle – the Jamais Contente – set the land speed record in 1899 at Yvelines near Paris, recording a top speed of a giddy 105.882 km per hour, and there is a story worth telling. At the turn of the last century Belgium with its powerful industrial base and great wealth was the epicentre of automotive innovation.

So, who were these motoring pioneers, what were the lost Belgian marques and manufacturers and what happened?

It’s a historical lesson in start-ups never quite fully reaching sustainable scale up, of Belgian ingenuity being either too far ahead of its time – the equivalent of Betamax losing out to VHS – or swept away by the competition from its larger neighbours. It is nevertheless a proud track record of entrepreneurship and innovation.

The story began in the 1880s, after German Carl Benz developed the first practical automobile and the concept was quickly copied by engineers around Europe. Belgians were quick to spot the potential of these horseless carriages. As a rich country, there was a market for the fantastically expensive, coach-built creations that began to grace the former stable blocks of the well-connected and the well-to-do.

The Jamais Contente was the creation of Belgian engineer Camille Jenatzy nicknamed Le Diable Rouge for his fiery ginger beard and love of speed. But Jenatzy was more than just a thrill-seeking speed addict. He was also a shrewd businessman who understood that the publicity he gained from breaking the land speed record would give his firm a competitive advantage over their bitter rival, the French coachbuilder Jeantaud, in the rapidly growing Parisian electric carriage market.

Poster for Jenatzy tyres

The fact that the fastest car in the world was an electric vehicle may come as something of a surprise to many, but the internal combustion engine had yet to establish its dominance. The jury was still out in a three-horse race (with no actual horses obviously...) between steam, electricity, and petrol. Like many other developments at the time – tiller steering versus steering wheels; the Levassor principle, where the engine is in front of the driver, versus rear engine – this was an age of experimentation. In terms of propulsion, on the streets of Paris and Brussels, electricity was in pole position.

Even at this early stage some of the current limitations of electric vehicles were present. While range was not an issue for a car built solely to go as fast as possible in a straight line, weight was.

The Jamais Contente sought to offset the huge weight of the lead-acid accumulator batteries needed to power it by having revolutionary partinium alloy bodywork made from a mixture of magnesium, aluminium and tungsten – another innovation that would take many years to re-emerge having lost the car bodywork battle to steel. Aerodynamic, low coefficient of drag coachwork – albeit severely compromised by the ridiculously high driving position and the fact that the streamlined torpedo bodywork sat on an old-fashioned cart-sprung chassis – was an innovation that would take a further 30 years to become mainstream.

Poster for Fabrique Nationale motorbikes

Unlike today’s electric vehicles, Jenatzy’s creation did not benefit from frictionless direct drive, but instead its twin Postel-Vinay 25kW electric motors were channelled to the rear wheels by an energy-sapping cog and chain drive. This, coupled with the tiller steering and unyielding suspension (despite the Michelin tyres) must have made the 68hp vehicle quite a handful and 100 km/h feel something like the equivalent of Mach 1. Indeed, when interviewed afterwards, Jenatzy said of the experience that it the car felt like a "projectile ricocheting along the ground.” While it may have won races, it certainly wouldn’t have won any prizes for driver comfort.

Steam, cigarette lighters and reverse gears

Not all early Belgian manufacturers opted for electric propulsion. Miesse, a Brussels manufacturer based in Rue des Goujons in Anderlecht, favoured the tried and tested technology of steam. Founded by Jules Miesse in 1874, Miesse’s early cars were powered by three-cylinder steam engines from 1896 until 1900. The chassis were made of reinforced ash hardwood and the boiler located under the bonnet.

The first Miesse petrol engine car appeared in 1900 and by 1904 the company had branched out into the motorised taxi market offering either a four-cylinder 2.0 litre or an eight-cylinder engine – the latter being an elongated version of the former. The firm also produced trucks to be exported to the Congo Free State. Miesse’s son took over the business in 1927 and decided to specialise in trucks and buses discontinuing car production. By 1929 Miesse had bought the Bollinckx works, allowing for an increase in its Junkers diesel-powered truck production to 100 per year. The firm survived for a century with the last vehicle – a bus – leaving the production line on July 12, 1974.

Miesse steam carThe list of early Belgian manufacturers is impressive but largely unfamiliar today – there were by some estimates more than 200 – a familiar picture across the industry globally at the time as former bicycle and armaments manufacturers sought to diversify into the newly emerging market.

Miesse steam carThe list of early Belgian manufacturers is impressive but largely unfamiliar today – there were by some estimates more than 200 – a familiar picture across the industry globally at the time as former bicycle and armaments manufacturers sought to diversify into the newly emerging market.

As was the case in Britain, mergers and acquisitions had radically pruned the number within a decade. Production was not concentrated in Brussels either but distributed across the country with one of the longer surviving marques, Minerva, based in Antwerp, and Imperia and Nagant in Liège.

Belgian manufacturers were not only pioneers in the field of electric propulsion but also the first with inventions like the electric cigarette lighter and the hybrid engine (Adrien Piedboeuf’s Imperia), and reverse gear (Delecroix). The Imperia factory at Nessonvaux, built in 1907 in the style of a medieval castle, even featured a one km rooftop test track years before the famous Lingotto Fiat factory in Turin or the Chrysler factory in Buenos Aires. Unlike Lingotto, Nessonvaux was not purpose-built but was a former armaments factory: the rooftop test track was added later following complaints from local residents about the factory’s tendency to road test their vehicles by driving around the town’s narrow streets at high speed.

The key early Belgian manufacturers were:

- Bovy, who produced trucks and light cars until the 1950s,

- FN, originally a weapons manufacturer (like the UK’s BSA), produced passenger cars until 1930,

- Excelsior, who lasted a similar length of time and produced sports and racing cars,

- Imperia, set up in 1904, who built sports and passenger cars until 1948,

- Nagant, another weapons manufacturer turned car manufacturer Metallurgique, focussed on the high-performance market segment until 1928,

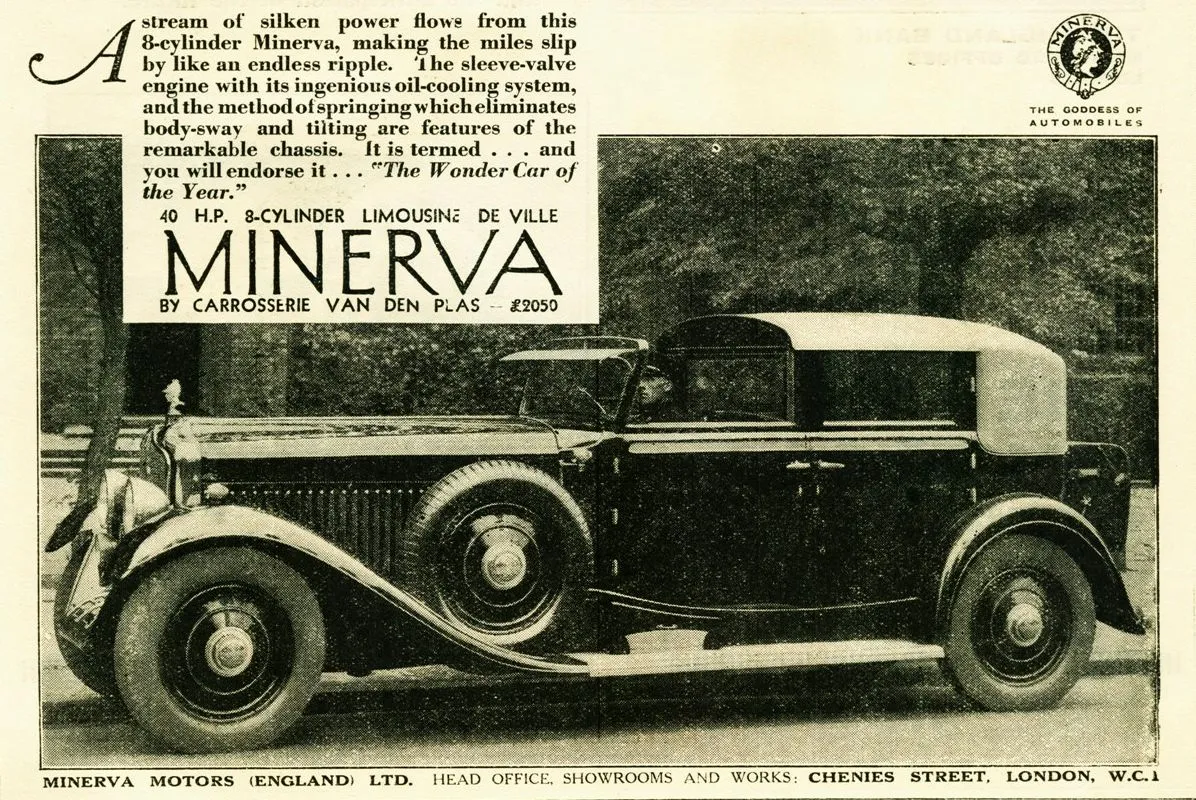

- Minerva, the ‘Belgian Rolls Royce’ and one of the longest surviving of the original Belgian pioneers,

- Vivinus, who sold German cars with Belgian coachwork,

- Delecroix, who pioneered the reverse gear,

- Pipe, a successful early race car manufacturer whose products competed in the Paris-Berlin races of the period.

Indeed, before the outbreak of World War II, Belgium had approximately 100 car manufacturers and a thriving export industry. At Autoworld, the car museum in the Cinquantenaire Park, a section dedicated to Belgium's automobile heritage displays 20 emblematic vehicles, including the Minerva, FN, Imperia, Belga Rice and Excelsior – and celebrates the inventors, industrialists, engineers, designers and even race car drivers that built Belgium’s car reputation.

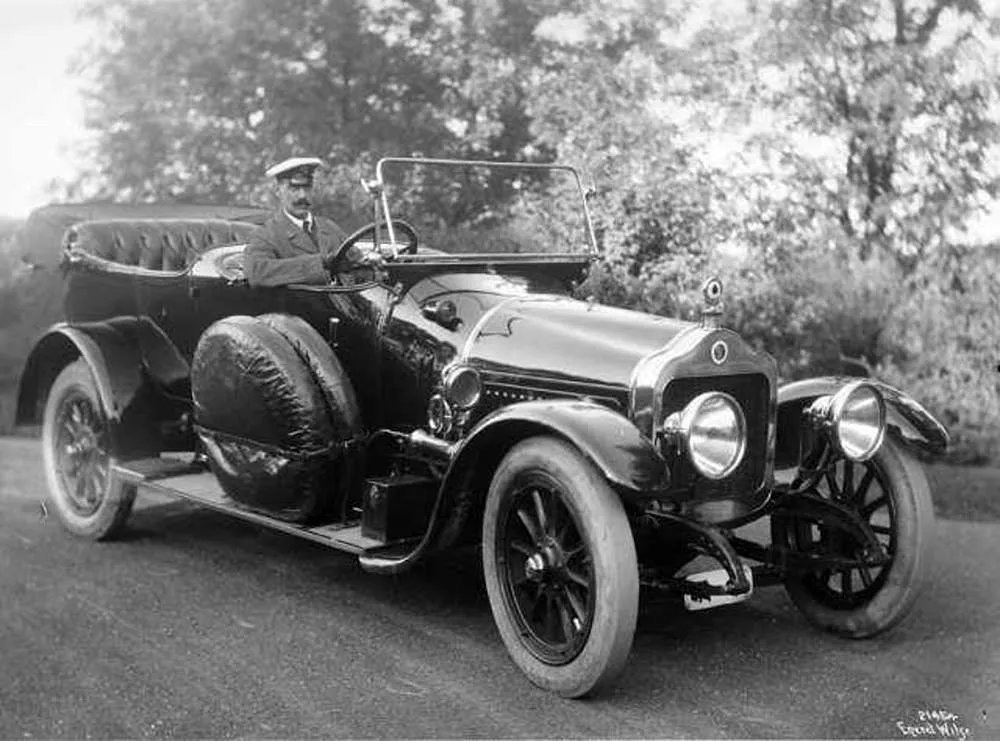

King Haakons of Norway in 1913 with a Minerva Torpedo.

Post Wall Street Crash however, US protectionism spelled the beginning of the end of a sector that produced vastly more vehicles than its domestic market could ever consume.

Consolidation was inevitable with Imperia taking over Metallurgique in 1927, Excelsior in 1929 and Nagant in 1931 before merging briefly with Minerva in 1934 only to get divorced five years later in 1939. Post-war, firms like Bovy the truck manufacturer and Brossel Freres the bus and coach builders found themselves merging before being taken over by the UK’s Leyland group.

Imperia eventually assembled Standard Vanguards in the late 1940s and 50s at its Nessonvaux factory until Standard Triumph built a new factory at Malines in Mechelen which opened in 1960 effectively putting Imperia out of business. The Malines Leyland Triumph factory was renowned for the quality of assembly (the full range from Heralds to TR4 sportscars being built there) with engines bench tested before being fitted and a legendarily good paint shop.

The British Motor Corporation meanwhile bought the factory at Seneffe in 1965 in Hainaut which had been built two years earlier by the Belgian MG main distributor. This became the main hub for British Leyland’s European operations employing 30,000 workers and running assembly lines producing over 3,000 Austin Minis, Allegros and Morris Marinas a day at its height in the mid-1970s. As Leyland Triumph was forced by the British government to merge with the insolvent British Motor Corporation in 1968, two factories were no longer required, and the smaller Malines plant eventually closed in 1975. The parlous state of the UK British Leyland, parent company led, in turn, to Seneffe’s closure in 1980.

The Imperia factory in Nessonvaux today

Luxury to workhorse

Minerva’s story is an interesting one. As with Rover in the UK, Minerva’s origins lay in the manufacture of safety bicycles and subsequently motorbikes – a promising coincidence as the two companies were to go into partnership in the early 1950s when Minerva won the contract from the Belgian army to build a version of the British Land Rover under licence.

This utilitarian, noisy and uncomfortable workhorse was a far cry from Minerva’s pre-war products which were very much at the luxury end of the market and were the transport of choice not only for the Belgian royal family but also for Hollywood stars and American industrialists.

Minerva’s first foray into internal combustion power had taken the form of motorised bicycles known as motorcyclettes: a small engine bolted onto the frame of a standard bicycle providing power to the wheels by a system of belts and pulleys. These ingenious motorbikes were the equivalent of today’s e-bikes: a relatively cheap and amazingly economical form of mass transportation. They were hugely popular far beyond Belgium’s borders – indeed the first British Triumph motorcycle was powered by a Minerva engine.

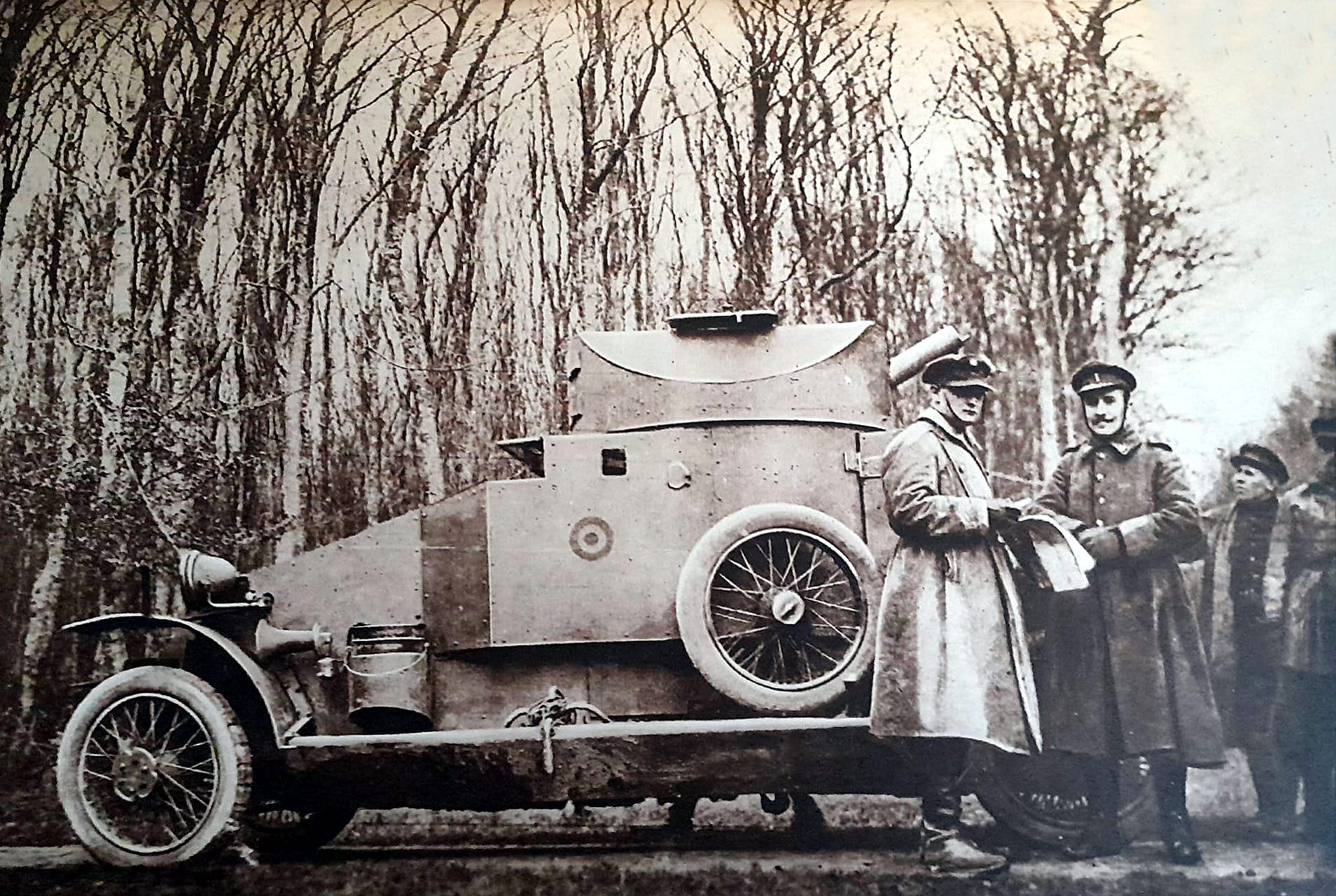

A Belgian Army armoured vehicle by Minerva

However, it was in luxury car production that Minerva excelled. Such was the quality of Minerva’s earliest offerings that before joining forces with Henry Royce in 1904, Charles Rolls was a luxury car dealer in London selling Minerva cars. The breakthrough for Minerva came when it secured the worldwide licence to produce American Charles Yale Knight’s ‘Knight’ engine. This, thanks to extra sleeving on its overhead valves, was virtually silent as well as both smooth and powerful. Engine sizes grew from straight six to straight eight cylinders and in the interwar period Minerva was a serious rival to Rolls-Royce with growing sales in the US and across Europe. This was all before the Wall Street Crash which forced its short-lived merger with Imperia.

Post-war, the Minerva Land Rover – a locally bodied (in steel rather than the UK equivalent’s Birm-a-Bright aluminium) was built under licence from Land Rover. Distinguishable to the trained eye by the sloping front wings (unlike the slab-fronted UK version) and different grille, Minerva Land Rovers not only mobilised the Belgian armed forces but also the Rijswacht. All was well until a breach of contract court case between Solihull and Antwerp – which Minerva won – soured the relationship and Land Rover decided to revoke the production licence.

Minerva’s demise soon followed in 1956 and with it seemingly the end of the Belgian pioneers. Seemingly, because even after the first pioneering wave, the Belgian motor industry continued to innovate. APAL produced sportscars using Glass Reinforced Plastic (APAL standing for Application Polyester Armé de Liege) from 1961 until as recently as 1998.

Assembling for others

The move away from the domestic pioneers towards Belgian assembly plants for foreign-owned manufacturers began in the interwar years with General Motors (Chevrolet and Cadillac) at Antwerp; Ford initially at Antwerp in the 1930s then subsequently at Genk; and Renault at Vilvoorde. Along with Leyland Triumph and the British Motor Corporation, these were mainstays of the Belgian automotive industry in the interwar and postwar periods. Not to mention the Audi Brussels assembly plant, which started out assembling Studebakers and VW Beetles in 1948, and has cranked out some eight million vehicles.

Belgian engineering skills, and high-quality production standards coupled with the country’s convenient geographical location and membership of the-then European Common Market made it an attractive choice for volume production. Ford at Genk was churning out 470,000 Sierras and Mondeos in 1994, the General Motors factory in Antwerp which became the European centre of Opel production until its closure in 2010 had originally opened on April 2, 1925, producing CKD Chevrolets and Cadillacs. This may explain why, following the demise of Minerva, the Belgian royal family opted for Cadillacs in the 1950s and 1960s as the preferred royal transport.

Grand Place when it was mainly used as a car park

So, what happened?

A process of adaptation and specialisation kept, and still keeps, the Belgian motor industry flame alight. Indeed, the Belgian automotive industry, in all of its branches, still employed 160,000 skilled workers in 2022 (over 2.6% of Belgium’s GDP). Belgium remains a centre of innovation and quality yet only has one remaining domestic car manufacturer – Gillet - as well as a bus manufacturer, Van Hool.

Gillet is a niche manufacturer based in Gembloux and founded in 1992 by Belgian racing car driver Tony Gillet. Its product, the Vertigo, is a handbuilt ultra lightweight supercar. Van Hool, the global bus and coach manufacturer, was founded in 1947 by Bernard van Hool (1902–1974) in Koningshooikt, near Lier filed for bankruptcy in April of this year and was saved a few days later when its trustees accepted a takeover bid from the Dutch company VDL (see separate article).

The Gillet Vertigo

Despite foreign manufacturers closing their factories due to global overcapacity and internal rationalisation – Renault in the 1990s, Opel in early 2010 and Ford in 2007 – the industry survives. There may be question marks over Audi in Brussels, but Volvo Cars and Volvo Trucks in Ghent are both cranking out top-of-the-range vehicles.

This is largely because the remaining assembly plants remain world class. Volvo Trucks in Ghent has an annual production of over 45,000 units. And Belgium is also a hub for sophisticated component manufacture. Ferrari and AMG high-performance transmissions are designed and produced in Zeldegem by Tremec. Automatic transmissions are built in Braine L’Alleud by AWEurope. Millions of components are manufactured by companies like VALEO, Continental and TYCO Electronics.

In addition, Belgium is the home of key research and development centres including Toyota in Zaventem and Ford in Lommel. On top of this are the customizers like Jem Design in Brakel, who are world leaders in aftermarket bodywork kits.

The success of Addax the e-truck manufacturer in Deerlijk shows clearly that today the focus has come full circle back to the zero-emission vehicles of Belgium’s automotive pioneers – they were 125 years ahead of their time.

If Jenatzy were here today, he surely would be smiling wryly. Far from being “jamais contente” he would say, “très contente.”