Until recently, Jan Fabre seemed unstoppable. An artistic force of nature, he was beloved in Belgium and seemed destined to see his creativity celebrated like the Flemish masters of centuries past. But amid a spate of sordid sexual allegations and an impending criminal trial, his carefully nurtured reputation could crumble. Fabre’s tale raises awkward questions about whether we can still appreciate his art or if it will be forever tarnished.

He is arguably Belgium’s most famous living artist. He is a multidisciplinary talent known for his provocative conceptual constructions, installations and theatrical productions that trick their eyes while pushing boundaries. His permanent public sculptures – a giant, metal beetle impaled on a giant pole in Leuven, a bronze giant turtle at the Namur citadel – were adopted as symbols of their towns. But in March, Jan Fabre will be in the dock in an Antwerp courtroom, facing up to five years in prison over allegations of violence, harassment or sexual harassment by former employees. What happened?

This is a complex story. Ahead of the trial, we should recognize that the allegations – which Fabre denies – need to withstand the legal demands of a criminal court.

But let’s start with Fabre as an artist. The 64-year-old from Antwerp has stretched his talent in many forms: painter, sculptor, writer and director. And he has never lacked controversy over his four-decade-long career.

“His works have always played with transgression and crossing borders, going to the limits, as a chance for deep insights, occasionally also like a game of ‘what can I get away with,’” says Bart De Baere, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (MUHKA).

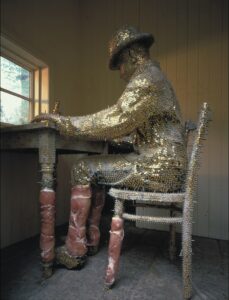

Ik, aan het dromen (Me, Dreaming), Credit: MUHKA

At his least controversial, starting in the late 1970s, Fabre used blue ballpoint pens on paper and fabric in defiance of classic art materials like paint and canvas in ‘Bic-art’ drawings, installations and several plays. For example, in 1990, Fabre covered Tivoli Castle in Mechelen with silk Bic-Art, changing something three-dimensional into two. The Gaze Within (The Hour Blue) (2011-13) Bic-art installation in the Royal Staircase of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts covers four walls, each of which displays a pair of eyes, of a woman, an owl, a butterfly and a scarab.

The blue colour refers to The Blue Hour, a concept coined by Fabre’s great grandfather, French entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre, who hugely influenced his art. It is “that magical moment between the end of night and beginning of day, the cleave of time, when all changes and all is possible,” explains MUHKA.be, which has many of Fabre’s works.

Artist provocateur

Fabre calls himself a “consilience artist” because he links principles from different disciplines like entomology and other life sciences to various forms of art. For example, his installation Heaven of Delight (2002) in the Mirror Room of the Royal Palace of Brussels includes 1.4 million emerald Thai jewel beetle shells on the ceiling and a chandelier, a project commissioned by Queen Paola of Belgium. Totem (2004) in front of Leuven’s Catholic University library displays a Thai jewel beetle skewered on a giant entomology pin. Fascinated by insects as a child, Fabre often uses them as subjects and materials in juxtapositions of life and death.

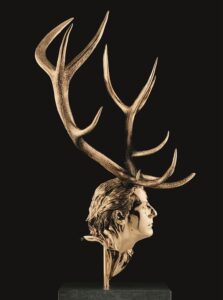

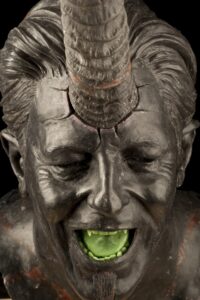

Fabre is fixated with metamorphosis, especially in self-portrait mode. In his ‘Chapters 1-18’ installation that he donated to the Royal Museum of Contemporary Art, he features 18 wax and 18 golden bronze sculptures of himself at different ages as animals. In 2008, as the first contemporary artist invited to exhibit at the Louvre in Paris, Fabre launched The Angel of Metamorphosis with a humanised snake atop tombstones, a lamb in a party hat and a peacock emerging from a casket among other animal-human combinations.

Fabre also has human-only self-portraits in bronze sculptures like The Man Who Measures the Clouds (1998) standing on a ladder, a tribute to his long-deceased twin brother, which sits atop Ghent’s Municipal Museum of Contemporary Art (SMAK), outside the ORSI Academy on the E40, and at Brussels’ airport; Searching for Utopia with Fabre riding a giant turtle on the citadel of Namur (2003) and in the coastal town of Nieuwpoort (2005); and The Man Who Bears the Cross (2015) in the Cathedral of our Lady in Antwerp, which combines the face of his late uncle.

Mur de la Montee des Anges, made with scarab beetles. Credit: MUHKA

At his most provocative, Fabre created a temporary installation at the University of Ghent in 2000 with 8,000 slices of ham wrapped in cellophane around eight neo-classical pillars. He wanted the spoiled meat to attract swarms of flies so that the pillars would “really be alive”. The colouring and gradients of the ham made the columns appear from afar to be made of red marble. (Some people protested the installation was a waste of food and defaced valuable architecture). During a 2012 performance at Antwerp City Hall, he threw live cats up a flight of stairs – an act of animal cruelty that resulted in 20,000 complaints and seven physical attacks.

But Fabre has also inflicted pain upon himself, using his own blood to create artworks every year since 1977. He has also used his tears (1980s+) and semen (1990s+) in visual arts – a throwback to early painters who mixed bodily fluids with pigments from nature – and even carved or crushed human bones into sculptures (when he dies, Fabre plans to have his brain, heart and skeleton turned into works of art).

Of all living things, the human body is Fabre’s main subject and object. “The body is like an incredible paint box, a laboratory, a battlefield,” he once said. “Everything that comes from it is very important. There is great knowledge to be found in our blood, skin, bones, sperm, and water.”

Searching for Utopia, Namur. Credit: Angelos bvba

While viewed by some as self-glorifying – “all his work really is self-centred” notes Pierre-Yves Desaive, curator of contemporary art at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels – these works are about as uncontroversial as Fabre gets. “He works with all kinds of materials – bronze, marble, extraordinary things – and finds people to help him with these materials,” Desaive says. “He likes to experiment.”

Desaive says nonetheless institutions should listen to what the public has to say and address societal issues such as #MeToo. “The worst thing we can do is act as if nothing is happening. After Fabre’s trial, my institution and others will definitely need to respond,” he says. But if Fabre is found guilty, will his art lose its value? “No, the work remains the work. But as a man, perhaps yes,” says Desaive.

Body of evidence

Fabre’s current troubles stem from his theatrical endeavours, which are much more intense. My Body, My Blood, My Landscape (1978) featured Fabre carving into his own body over several days to make blood drawings. In The Crying Body (2005), actors urinated on stage. Mount Olympus (2015) depicted the “hubris, blindness and cravings of man” in a 24-hour show with the same actors. His most recent production, The Fluid Force of Love (2021), explored freedom of sexuality and gender identity.

“He is an energetic performer who explores the limits of theatrical admissibility,” writes Hans Willemse on MUKHA.be. “Urges, desires, beauty and mortality are recurring themes, both on stage and in his visual work…Fabre fantasises, glorifies and brandishes to remind us of decay and destruction, of blood and suffering, of the animal in man and the human in the animal.”

Peter Bernaerts, managing director of Bernaerts Auctioneers in Antwerp, who sells some of Fabre’s works, says his art is about exploring the human condition. “He’s an artist that’s holding a mirror for society. He tries to show the viewer on stage this is what a human being is about: pain, exhaustion, panic, everything we don’t want to see too much,” he says.

The Gaze Within (The Blue Hour) at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels. © Angelos bvba

In art, boldness can be exhilarating, Bernaerts says. “He’s a rebel,” he says. “He’s always looking how to break conventions. There are no boundaries. Fabre makes art dangerous to look at and feel. You feel relieved and horrified at the same time.”

But Bernaerts accepts this creates issues with personal space. “He invites his players, maybe forcing them, to step over their own limits on stage. Live, it’s difficult to see. You feel committed and responsible as a viewer and embarrassed about being human,” he says.

Fabre claims he wants to address societal taboos so he can “normalise” them. “The body is the entrance to every emotion, thought and higher contemplation,” notes Angelos.be, Fabre’s visual arts website. “Fabre uses interventions on his own body to explore its fluid boundaries. This is an endless quest for the self, the shell which serves as the entrance to deeper contents. The artist’s enduring fascination with the body is also on display in the personal actions and performances, from 1976 to today.”

It is this obsession with the body that could be Fabre’s downfall. He now looks stranded on the wrong side of modern societal taboo, accused of abusing his power in exchange for sex, in a now all-too-familiar #MeToo situation.

Courts of law and public opinion

Fabre will stand trial in Antwerp on March 25 and April 1 on charges of sexual harassment and indecent assault following a three-year investigation by the Flanders Department of Culture, Youth and Media into his performing arts company, Troubleyn, which had received millions of euros in government subsidies over the years. The probe was sparked by a letter sent to the Dutch art magazine rekto:verso by 20 former performers and apprentices who alleged they “had been navigating unprofessional and inappropriate relationship practices in the workplace for decades.”

These practices allegedly included humiliation, intimidation and coerced sexual acts in exchange for money and performance time or demotion when the latter was refused. Employees were invited to "semi-secret" photography sessions and urged to take drugs to "feel more free" to meet sexual demands.

Ironically, Troubleyn.be states that it “envisions a world where diversity is celebrated and all people are respected, valued and affirmed inclusive of their sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression…no one should face stigmatisation, violence, or abuse on any grounds.”

Fabre’s accusers may have taken his advice. “We ask the artistic community to support and invest in this conversation,” wrote the mixed-gender group. “Together we will no longer support a culture of hypocrisy and denial in the name of art.”

Yet rather than stepping up and speaking out, the Belgian art community has clammed up about Fabre as the trial nears. Given this small country and the small art world within it, few in the community – from art historians to gallerists and museum/performing arts centre directors – were willing to be quoted for this story out of fear of it impacting their business or reputation.

Chapter XIV in bronze, Right: Chapter VII in wax. Credit: Angelos bvba

The theatre world has acted already, closing its doors to Fabre’s shows in 2021 in Belgium, elsewhere in Europe and the United States (his last show was performed in France in October).

Others, however, struggle to separate Fabre the artist from the individual because he focuses so much on the human body and body politics and publicly expresses values related to it. But no one contacted for this story, not even women, were willing to say so, at least not before the trial.

“Everyone is afraid of consequences if they speak out about Jan Fabre,” sculptor Luc Cauwenberghs, who built Fabre’s turtle for Nieuwpoort.

Fabre has not had any art exhibitions since early 2020. “It’s quite quiet around Jan Fabre now. He’s not making new sculptures or other works,” Cauwenberghs says. “He could come back after four to five years. But if he does, it won’t be the same. There was a moment in Belgium 20 years ago when Fabre was like a king. But not any longer.”

Cauwenberghs says the art market has moved on anyway. “Big works of Fabre were bought by banks and companies because they were costly. Now these works are worth less. Conceptual art is decreasing in importance in Belgium.”

Censorship?

Last year, the deSingel international arts centre in Antwerp returned The Man Who Measures the Clouds to Fabre after removing it for rooftop renovations. “In 1999, this work of art by Jan Fabre was placed on the roof of deSingel,” it says on deSingel.be. “For us, this work has lost its artistic relevance since then…the sculpture symbolizes a cult of self-glorification with which we as a house do not identify. The fact that the sculpture in that place in 2021 is perceived as offensive to certain people is also an argument…deSingel is a house where everyone feels welcome and recognized. We are convinced that the decision not to return the sculpture will contribute to this.”

However, SMAK, where the same sculpture has been on its roof since 1998, and several others do not agree. “We are not removing Fabre’s sculpture as a result of the allegations against him, rather, we intend to have conversations around the #MeToo movement this year to publicly deal with the topic,” says Artistic Director Philippe Van Cauteren. “Removing sculptures doesn’t address societal issues. Artwork stands on its own.”

Geert Verbeke, co-founder of the Verbeke Foundation in Kemseke, Belgium and contemporary art expert, says the art and the artist should be considered separately. “He’s very difficult. But I’m also very difficult!” he says, half-joking. “Everyone does something wrong in their life, so I won’t judge if he is convicted, nor sell his works in my collection. I believe in second chances. But for some people, the court outcome will change their perception.”

Verbeke says only time will tell if Fabre remains an influential figure after the trial. “It’s all about the work, not the person. I don’t think Fabre should disappear. His works are very good. deSingel made a choice that I will not,” he says.

Chapter VII in wax-Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. © Angelos bvba

He likens Fabre’s situation to two collage artists, Willy Kessels and Mark Emans, who collaborated with the Germans during World War II and were later shunned as artists. “It’s a shame because their works were good,” Verbeke says. “And Fabre deserves his place in the art world. There are not many artists who can cope with multiple forms. He dared to do many things. He didn’t follow others; he was very original and authentic.”

Michelle Martens, director of Nieuwpoort’s tourism office notes the allegations against Fabre have had no impact on his turtle sculpture in her town, which has been a tourist attraction since 2003. “Most people don’t know it’s his sculpture and it’s a magnificent piece of art, no matter the artist. For us, those are two different things.”

Nonetheless, she concedes that Fabre is “not a blank artist anymore” and the city council will have “carefully consider” whether to exhibit or purchase additional works by him.

Moral dilemmas

The moral dilemma is at the heart of the matter. Do we have a responsibility to address these tricky questions and speak out? How does society evolve if the issues that plague it are not openly discussed?

Fabre’s case could inspire action. It forces us to ask questions of ourselves about values and society. For instance, are we less forgiving of media personalities than artists in the face of a scandal? Take Belgian television presenter Bart De Pauw, who was found guilty in 2021 of stalking five women and “nuisance with electronic means of communication” of a sixth. He was sentenced to six months of probation for non-physical acts, while a documentary on him, The Trial That Nobody Wanted, debuted on Streamz shortly after. While De Pauw’s job was spared, there was a strong public reaction to his allegations and charges.

Totem: a Thai jewel beetle skewered on a giant entomology pin in front of Leuven's Catholic University library. Credit: Jan Crab

Perhaps that’s because such media personalities are inside our homes and seem like people we can trust, whereas artists and other professionals are at a distance whom we rarely see. Does this create a psychological distance that makes them less accountable to the court of public opinion? There are countless examples of famous cultural icons who have fallen from grace: Michael Jackson, Bill Cosby, Roman Polanski, Woody Allen, Kevin Spacey, Phil Spector and Eric Gill (whose sculpture at BBC headquarters in London was attacked in January 2022 due to his incestuous past) to name a few. But many still appreciate their artistic contributions.

The societal debate also depends on the country and culture. In the United States, painter and photographer Chuck Close was accused by six women in 2017-18 of sexual misconduct. Shortly after, he was removed from the Dean’s Council at Yale’s School of Art and his exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC was cancelled (after Close died in 2021, his neurologist said that the artist’s inappropriate sexual behaviour could have been due to frontotemporal dementia).

Market values

While Fabre has had a similar fall-out with cancelled performances and stalled exhibitions, so far there has been no correlation between the allegations and the value or sales of his art.

Moreover, ArtPrice.com, which lists results from auctions per artist, shows that between 1992 and 2021, nearly 40 percent of Fabre’s works did not sell, regardless of the 2018 allegations.

Sterenn Denys, a Belgian art advisor and dealer, says the market is still driven by money, and Fabre is a falling stock. “If private collectors speak of his work, it is more about financial values than the quality of content or messages it carries,” she says. “There is not much demand from art collectors to own a Jan Fabre. Actually, auction houses have sold very little of his work.”

Denys says the allegations against Fabre are all too frequent in the art world. “Perhaps such allegations will inspire the art market to think over its own system. Is it meritocratic or not and what moral values does it carry? Things are moving, but extremely slowly because there is a lot of resistance,” she says.

Bernaerts, the Antwerp auctioneer, says deSingel’s removal of Fabre’s sculpture, a deliberate delegitimization, poses problems for art. “We must make a distinction between artists and themselves. Otherwise, should we stop seeing the movies of Quentin Tarantino? This could be a type of censorship. An artist puts out his vision, not values, but an artist is there to question values. We have to preserve artists to know what is wrong or good in our society.”

Bernaerts says he expects the trial to confirm the accusations. “I thought immediately that he was guilty. Fabre has this reputation and a feeling of invincibility,” he says. But Bernaerts doesn’t think that will change Fabre’s legacy. “Fabre is the number three artist in Belgium after Luc Tuymans and Michaël Borremans and number one as a multidisciplinary artist. After 40 years in business, he is still talked about. He will remain relevant for years to come. No one is doing what Fabre does. He has made his mark on the world with his art.”

Fabre’s The Man Who Measures the Clouds refers to Robert Stroud, known as the Birdman of Alcatraz, a notorious prisoner and self-taught ornithologist who supposedly said after his release, “I’m going to measure the clouds.” Will Fabre do the reverse commute? If so, can – and should – we separate him from his art? That would mean measuring the man and not the clouds.