The Aegidium on the Parvis de Saint-Gilles has been boarded up for decades, but now, the Art Nouveau marvel is finally being restored.

If you wanted to see a cabaret show in Brussels in 1906 and had no issue riding up to the Parvis de Saint-Gilles, you would have headed to the dazzling Diamond Palace, which opened that year.

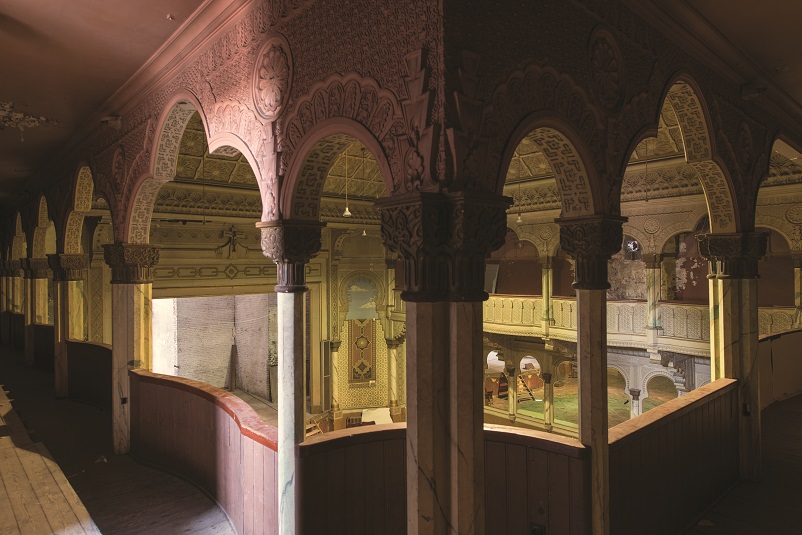

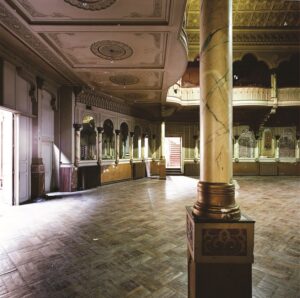

Its neoclassical, eclectic façade may have been unassuming, but venturing inside, punters would have found a magnificent Art Nouveau interior, mixed with elements drawn from the Louis XVI decorative style, such as floral garlands, putto figures and medallions. It boasted electric lighting – a novelty at the time – and was bedecked with mirrors from the arching hall entrance all the way to the sweeping staircase that leads to the vast theatre. There, Byzantine columns and Moorish arches would have sparkled under 5,600 brilliant filament light bulbs on the ceiling above the audience.

“It was also called the Diamond Palace as the mirrors work with these lights as well,” architect Francis Metzger, describing the original theatre’s luminous past. “The mirrors and the brightness give a type of fairy-like environment. It gives us an atmosphere of a party.”

That was then. The building, designed by architect Guillaume Segers, later became a dance hall, changing names to the Panthéon Palace. In 1929, local priest Gaspar Simons bought the hall and rebaptised it the Aedigium, linking it to commune itself: Saint Gilles, also known as Giles the Hermit, is Aegidius in Latin. By 1933, it once again changed vocation, becoming a cinema.

But then the theatre closed in the 1960s. Although the ground floor was briefly transformed into a day centre in 1979, it closed definitively in 1985 because of fire safety risks, plunging it into decades of darkness.

Haunted theatre

Today, the Aegidium is one of the city’s hidden Art Nouveau gems. Although the ground floor café has remained in use, the remainder of the building was hoarded off.

“The first time I saw the Aegidium I felt absolute sadness, absolute sadness,” says Metzger, who has been tasked to restore the 4,000 square-metre, heritage-listed venue. “It had been sort of camouflaged, unseen for decades. Fake ceilings covered the work, boards covered the walls, the columns were hidden as well as the original art. It was painted white. All these changes were a great loss, so when you enter for the first time you don’t see it, but you feel it. You ask yourself, ‘What happened here?’”

Visiting the Aegidium on a blustery January day, the light still shines on its past splendour. Although the colours on the walls have faded, and the velvet of the balcony chairs ripped, the energy in those rooms still reverberates somehow.

In the long hall with a curved ceiling, many of the mirrors are missing or broken, while the walls below are bare. A ‘Diamant Palace’ faded poster still clings to the brick exposed in the restoration work.

The eyes turn to the stairwell, a flowing mount of pink granite illuminated by an exceptionally large and ornate oval glass skylight held together by pieces of iron. From the ceiling hangs a large chandelier made up of flowers with crystal petals. At the top of the stairs is a lattice frame over the theatre doors, from which faded grey beige paint is peeling off.

The staircase next to the theatre entrance

And then, the theatre hall itself: columns draped with gold leaf, more marble, and Moorish stucco porticos. The original piano is still there on the bare floorboards of the stage. The empty balcony where the applause of Brussels theatregoers once echoed, is now silent.

Revival

But what happens now? The building is both a construction site and a haunted theatre. The facade, the theatre, the entry and the roof are all heritage listed which means there are complex legal obligations for the restoration. The past few years have been spent in uncovering its buried past, removing the makeshift additions added over the decades, and bringing its original features back to the fore.

“The first thing and the first difficulty when you’re an architect is to understand how the building has evolved since 1906,” Metzger says. “In those 115 years, what is original and what isn’t? Fundamentally for the work of heritage and restoring history, the only real question is ‘What constitutes architectural design?’”

The theatre is part of a bigger building on the Parvis which will be turned into an innovative creative hub by Cohabs, a co-living residential specialist, alongside Alphastone a real estate investor. It has taken eight years to get to an agreed plan for the project: the restored theatre and the heritage-listed spaces will co-exist alongside the co-living and creative areas.

The building will be cut up into different spaces including co-working, co-living, conference areas, a fablab (fabrication laboratory, a workshop offering 3D printing), a restaurant and the restored theatre.

By the time the theatre is restored over the next two years, it will be the new home of Le Public theatre, currently based in Saint-Josse. It will have three halls, two rehearsal areas and one main theatre.

But for Metzger, who also oversaw the renovations of Villa Empain, this is about bringing an Art Nouveau icon back to life. “We need a balance between what could be useful and function as a theatre today, and preserving the heritage of the design,” he says. “There is nothing like that building in Brussels’ architectural history.”