The Jewish Museum of Belgium, located in Brussels, is currently showing the exhibition ‘Moroccan Women - Between Ethics and Aesthetics’ with focus on dresses and jewelry used in the past by both Jewish and Muslim women in Morocco.

The exhibition can be described as a narrative journey through a wide range of objects from the 16th century to the present: traditional and religious objects, clothing, ornaments, talismans and jewelry, archival documents, photographs, drawings and orientalist paintings. The vernissage in December attracted a large audience of local Moroccans and young Belgian people.

“I didn’t expect such a big interest in the exhibition,” Paul Dahan, who curated the exhibition, told The Brussels Times. “It shows the fascination and interest in knowing more about a beautiful multicultural phenomenon which was shared by Jews and Muslims alike in Morocco. This culture cannot be forgotten by people with a Moroccan background living in Brussels and elsewhere.”

Paul Dahan, a psychoanalyst by profession, not only curated the exhibition but also collected all the objects in it. Since he arrived in Brussels because of its multicultural diversity, he has collected ca 3,000 objects and only some of them were exhibited this time.

“In my work, I deal with how our memory of the past influences us in our lives today,” he said, explaining his passion for collecting art objects from his homeland.

He is a member of the Council of the Moroccan Community Abroad and has long experience of organizing exhibitions about Morocco. In for example 2010, he curated an exhibition which was shown both in Brussels and Rabat about Morocco’s relations with Europe during six centuries. The exhibitions are organized under the patronage of the king of Morocco.

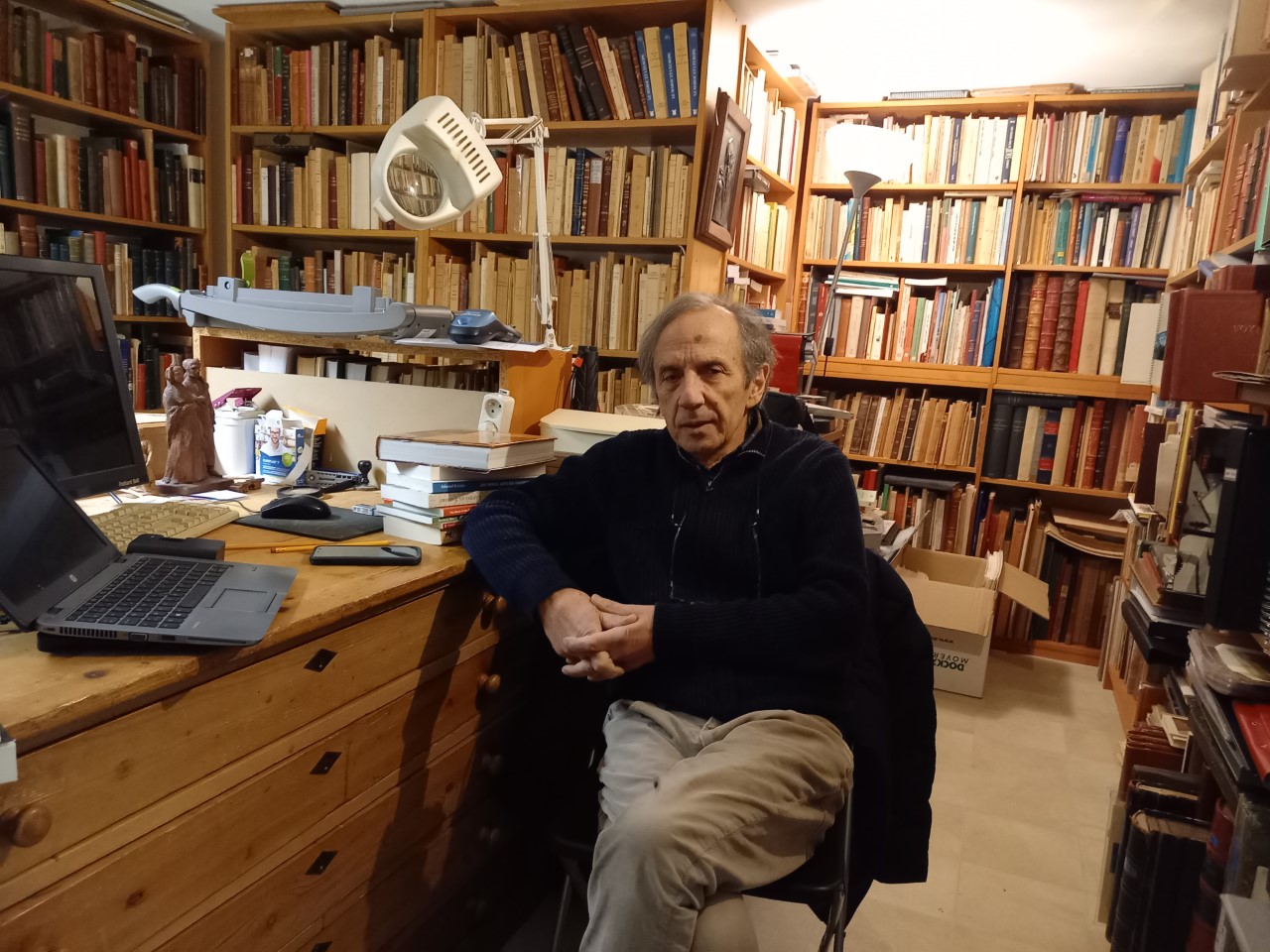

Paul Dahan in his office at the museum, credit: The Brussels Times

We met at his office in the basement of the museum, which has its own story to tell. The museum building is a former German-speaking school for girls and was used by the Nazi occupation force during WWII. Passing to his office, he showed me cells where resistance fighters and communists had been imprisoned. His office is filled with books about the history and culture of Morocco.

The objects in the exhibition, especially the women dresses, are extremely beautiful and that explains the aesthetics part of the exhibition but what has it to do with ethics?

“It’s a matter of how men perceive and are attracted to women dressed in different ways,” he explained. “If we judge women by stereotypes, or generalize about them, it becomes a moral question. But in these elaborate costumes, you hardly see the women. What attracts the eye is the costume. From that point of view, men cannot react negatively to the women wearing them.”

Do the costumes worn by Jewish and Muslim women differ?

“In principle not. The main difference is that a Jewish woman also wears a wig to cover her hair although the wig is hardly noticed because it’s covered in a head dress. A Muslim woman normally wears a veil but not necessarily everywhere in Morocco, depending on local customs.”

The majority of Moroccan Jews had arrived from Spain (‘Sepharad’ in Hebrew) and Portugal after the Catholic expulsion from those countries more than 500 years ago. It might come as a surprise that Sephardic Jewish women also were wearing wigs as this today is mostly associated with Orthodox Ashkenazi women (originating from Germany and Eastern Europe).

“In both cases, Jewish and Muslim, it was the male-dominated society which set the rules, Paul explained. “A virtuous woman had to cover her head or face not to draw the attention of men.”

There were also differences within the Jewish society in Marocco. Those who were expelled from Spain and arrived in the western-northern part of the country brought their own rich costume traditions. They used dresses that were composed of many parts while the Berber Jews in the Atlas Mountains used simpler dresses. Jewelry was an integral and expensive part of the costumes and included different symbols.

Jewish jewelers preserved ancient techniques inhered from the Andalusian period in Spain. They also invented new methods of production which spread throughout Morocco. Jewelry came in all shapes and sizes: necklaces, bracelets and large ear-rings. There were also circular brooches that were pinned to women’s clothing.

Were the dresses made at home or ordered from tailors and professional seamstresses?

“They were ordered from artisans in the market place and were mainly made by Jewish tailors and seamstresses, both for Jewish and Muslim women. It could take a year or so to produce these dresses which were made for a wedding. They were thus expensive and the parents would have to save money to afford to buy a dress for the daughter to her wedding.”

“But it could also be seen as an investment because the dress was inherited in the family for generations. The costume was not an every-day dress and only used at big events and festivals.”

Are they still used in Morocco?

“They started to disappear in Morocco as from the 1920-ies, a process which was accelerated after WWII,” Paul replied. “You can hardly find them there any longer, at least not in those parts of Morocco where the Jews settled after the expulsion from Spain.”

“Nor can they be found in Israel to where the majority of Moroccan Jews arrived after the establishment of the Jewish state in 1948. They were destitute, having left everything they owned behind them, and didn’t think of preserving their costume traditions. Possibly you can still find these costumes in Jewish communities in other parts of the world where Jews from Morocco have settled.”

There is a special room in the exhibition on tatous. Are tatous not forbidden in Judaism?

“That’s correct but they were quite common among the Berber Jews who had been living in Morocco since ancient times before the arrival of Islam. They were living a more isolated life in the mountains and influenced by the non-Jewish Berber tribes, the indigenous inhabitants in North Africa.”

The exhibition is a good example of Jewish-Moroccan cooperation and their common interest in preserving Moroccan culture. It will run until 30 April 2023.

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times