He placed tenth in the 2005 listing of the greatest Belgians for Wallonia, but how many of Georges Simenon’s compatriots are aware of just how important the writer was? In the 21st century, is he a prophet without honour in his own country?

Certainly, Simenon’s influence as a crime novelist is incalculable. Interviewing for the various books I have written on crime writers from around the world, again and again, Simenon came up as a touchstone for many of his fellow writers, including Henning Mankell in Sweden, Andrea Camilleri in Italy and John Banville in Britain.

Georges Simenon created a furore worthy of the most bed-hopping of politicians with his 1971 autobiography, in which he mentioned having sex with over 10,000 women. This jaw-dropping claim was met with scepticism: how had he written so many novels if his entire time seems to have been spent in carnal abandon? Simenon admirers were alienated by what seemed like boastfulness – but one doesn’t have to approve of all a writer’s statements to admire his work. Leaving such things aside, by the time of his death in 1989, Simenon was the most successful writer of crime fiction in a language other than English in the entire field, and he had created a writing legacy quite as substantial as many more ‘serious’ French literary figures.

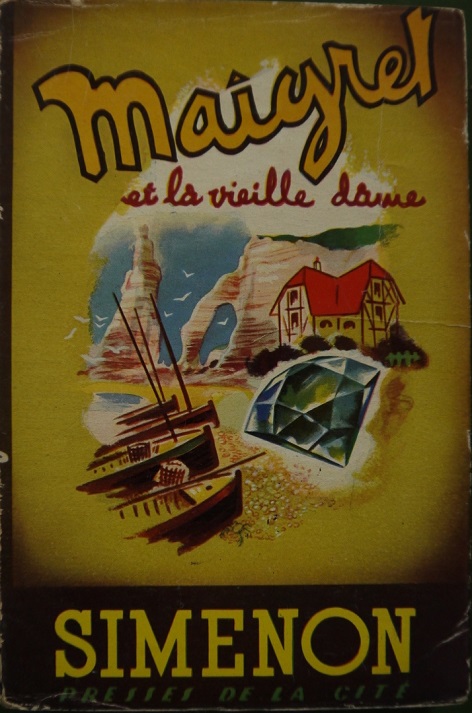

Simenon was astonishingly prolific, publishing nearly 500 books, many under pseudonyms. His most iconic creation is, of course, the pipe-smoking Inspector of Police Jules Maigret (Belgium is credited with two other world-famous detectives, Hercule Poirot and Tintin, but Maigret reigns supreme).

All the elements that made the character so beloved were carefully burnished by the author: Commissaire in the Paris police headquarters at the Quai des Orfèvres, Maigret is a much more human figure than the forbidding analytical sleuth Sherlock Holmes, and his approach to solving crimes is more dogged and painstaking than the theatrics of other literary detectives – an innovation in its day.

Simenon’s protagonist is a quietly spoken observer of human nature who uses the techniques of psychology on those he encounters (both the guilty and the innocent) – without immediate moral condemnation. Simenon gave Maigret a role in the vice squad in his early career, but sans the tongue-clucking disapproval that was the establishment view of prostitution at the time (Madame de Gaulle famously sought – without success, of course – to have all the brothels in Paris closed). Maigret, with his eternal sympathy for the victim, saw these women in a non-judgemental fashion and remained sympathetic, even in the face of dislike and distrust from the girls themselves.

One of his 75 Maigret novels

Beyond Maigret, Simenon’s standalone novels are among the most commanding in the genre – notably The Stain on The Snow, an unsparing analysis of the mind of a youthful criminal. Nobel laureate André Gide’s assessment of Simenon as “the greatest French novelist of our times” may have been hyperbolic, but as a trenchant picture of French society, Simenon’s books collectively forge a fascinating analysis.

Nihilist clique

Georges Joseph Christian Simenon was born in Liège on February 13, 1903. His father worked for an insurance company as a clerk, and his health was not good. Like Charles Dickens in England before him, Simenon had to work off his father’s debts, giving up the studies he was enjoying and toiling in a variety of dispiriting jobs (including, briefly, working in a bakery).

His first experience of writing was as a local journalist for the Gazette de Liège. It was here that he perfected the economical use of language that was to be a mainstay of his writing style, and Simenon never forgot the lessons he acquired in concision.

Even before he was out of his teenage years, Simenon had published an apprentice novel, and he became a member of an enthusiastic organisation styling themselves The Cask (La Caque). This motley group of vaguely artistic types included aspiring artists and writers, along with assorted hangers-on. A certain nihilistic approach to life was the philosophy of the group, and the transgressive pleasures of alcohol, drugs and sex were actively encouraged, with winding-down periods in which these issues – and, of course, the arts – were hotly debated. All of this offered new excitement for the young writer after his sober teenage years.

Simenon had always been attracted to women (and continued to be enthusiastically so throughout his life) and in the early 1920s he married Règine Renchon, an aspiring young artist from his hometown. The marriage, however, was not to last.

Despite the bohemian delights of Liège’s Cask group, it was of course inevitable that Simenon would travel to Paris, which he did in 1922, making a career as a journeyman writer and publishing many novels and stories under a variety of noms de plume.

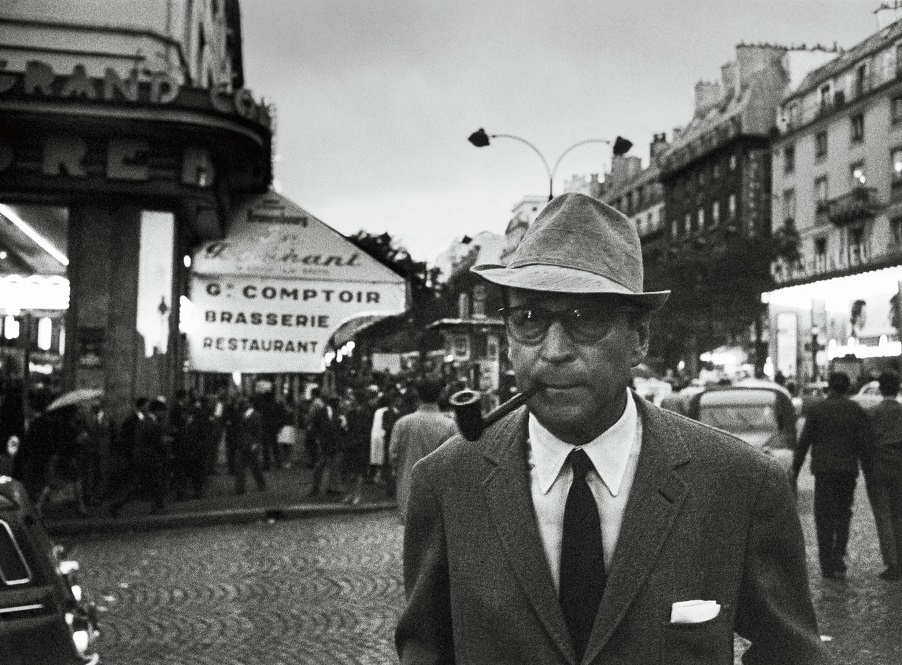

Simenon in Paris

Simenon took to the artistic life of Paris like the proverbial duck to water, submerging himself in all the many artistic delights at a time when the city was at a cultural peak, attracting émigré writers and artists from all over the world. He showed a particular predilection for the popular arts, becoming a friend of the celebrated American dancer Josephine Baker after seeing her many times in her well-known showcase La Revue Nègre. Baker was particularly famous for dancing topless, and this chimed with the note of sensuality that was to run through the writer’s life.

As well as sampling the fleshpots of the capital, along with more cerebral pursuits, Simenon became an inveterate traveller, and in the late 1920s made many journeys on the canals of France and Europe. Even as he wrote his police procedural novels with the doughty Inspector Maigret (his principal legacy to the literary world), he would say that the more experience in other countries he accrued, the better a writer he would become.

Simenon’s life was to change as the war years approached. In the late 1930s, he became Commissioner for Belgian refugees at La Rochelle, and when France fell to the Germans, he travelled to Fontenay. His wartime experiences have always been a subject of controversy. Under the occupation, he added a new string to his bow when a group of films was produced (under the Nazis) based on his writings. It was, perhaps, inevitable that he would later be branded a collaborator, a stain that would stay with him for the rest of his career.

Atlantic crossing

After the war, Simenon relocated to Canada, with a subsequent move to Arizona. North America had become his home when he began a relationship with Denyse Ouimet, and his affair with this vivacious French-Canadian would be highly significant for him, inspiring the 1946 novel Three Rooms in Manhattan. The couple married, and Simenon moved yet again, this time to Connecticut.

Towards the end of the 1940s, Simenon became convinced that he was going to die when a doctor made an incorrect diagnosis based on an X-ray. The Belgium-set novel Pedigree from 1948 (which we’ll come back to later) was written under this erroneous sentence of death, but Simenon’s time was not yet up. However, always attracted by the prospect of a new relationship, Simenon began to neglect his wife and started an affair with a servant, Teresa Sburelin, with whom he set up house (his wife Denyse ended her days in a psychiatric home.)

By then, Maigret had become as much of an institution as the author. The books create an extraordinary panoply of French society, with social criticism in there, too – Maigret is always searching for the reasons behind crime, and sympathy is as much one of his qualities as his determination to see justice done.

Whereas modern officers such as Ian Rankin’s Inspector Rebus are rebellious mavericks, eternally at odds with their superiors and battling personal issues, Maigret is a classic example of the French bourgeoisie, ensconced in a contented relationship with his wife. There is no alcoholism, but rather an appreciation of fine wines – and, of course, a cancer-defying relationship with a pipe (the sizeable pipe collection on his desk rivals Holmes’ Meerschaum pipe as a well-known detective accoutrement).

Simenon's statue in Liege

Pedigree is among the novels in which no continuing detective figure features, and it is the key to understanding Simenon both as a writer and as the product of a Belgian upbringing. One of the most powerful and the most ‘Belgian’ of his books, it is also the most autobiographical, although the author himself did not like it described in this way. The novel tells the story of the childhood in Liège of Roger Mamelin, from his birth in 1903, the same year as Simenon’s, to the end of the First World War.

Pedigree vividly evokes the experiences of growing up and all the sights and sounds of Liège. Several characters can be recognised as portraits of Simenon’s family. He stressed that it was written completely differently to his other works and noted that it was unique in his output.

Above all, while recognising that the central character has much in common with himself as a child, Simenon still wanted it to be considered a novel: “I would not even wish the label of autobiographical novel to be attached to it,” he said. To make the distinction clear, he added that, “in my novel, everything is true while nothing is accurate.”

Barry Forshaw’s Simenon: The Man, The Books, The Films is published by Oldcastle and is available from Amazon