Time has not withered Tintin. He may be fictional, he may have emerged from comic books, but he is still an inspirational adventurer for all time.

In the pantheon of comic book heroes, few can boast his enduring popularity and influence. Yes, he sometimes sported plus-four trousers and a cloth cap above his narrow quiff of blond hair, but his style is eternal. Belgium's greatest hero is a role model not just for leads in comic strips, but for those in books, movies, television and video games.

But it's not just his cultural significance that makes Tintin so enduring. It's his universal appeal. Tintin's adventures take him all over the world, from the depths of the Amazon rainforest to the icy wastelands of the Arctic. He's a hero who transcends national boundaries, and his stories are just as relevant today as they were when they were first published, almost a century ago.

Tintin’s creator was, of course, Hergé. His real name was Georges Remi: his pen name comes from the French pronunciation of his inverted initials, RG. Born in Etterbeek in 1907, he was just 21 when he conceived of Tintin, who made his debut on January 10, 1929, in Le Petit Vingtième (The Little Twentieth), the weekly youth supplement of the Belgian daily newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle (The Twentieth Century).

Like many writers, Hergé seemed to channel a wish fulfilment into his boyish, daring and globetrotting protagonist. And though he launched Tintin at such a young age, there were precursors to the intrepid adventurer.

When he was just 18, Hergé created Totor, a Belgian scout leader who finds himself caught up in far-fetched adventures in Texas. The series ran for three years in the scouting magazine Le Boy Scout Belge.

While crudely drawn, Totor includes key elements that would later define Tintin. There is the form of Totor, from the clear outline and simple face. There is a switch from captions under the panels to speech bubbles. And there is the character: Tintin’s actions and outlook owe everything to the boy scouts. Hergé himself joined at the age of 12 and would travel to scout summer camps in Italy, Switzerland, Austria and Spain, even hiking hundreds of kilometres over the Pyrenees and Dolomites.

Hergé with his creation

Hergé took inspiration from a variety of sources, including adventure novels like Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island and Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. But his venture into comic strips was spurred by the emerging medium of cinema. From the animations developed by the likes of Walt Disney in the early 1920s to the comic genius of pratfall pioneers like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, Hollywood left an indelible impression on the young Belgian artist.

Ligne claire

Hergé would join Le Vingtième Siècle initially as a clerk and then as an illustrator. This was not just a conservative, Catholic newspaper, but often fascist and antisemitic. Its editor, Abbé Norbert Wallez kept a signed photograph of Benito Mussolini, the Italian Fascist leader on his desk. When Hergé was ready to launch Tintin, he wanted to send him to America for his first adventure, following in the footsteps of Totor, but Wallez insisted that he visit the Soviet Union, where he would expose the communists for their assumed cruel gangsterism.

The early books were serialised in Le Petit Vingtième

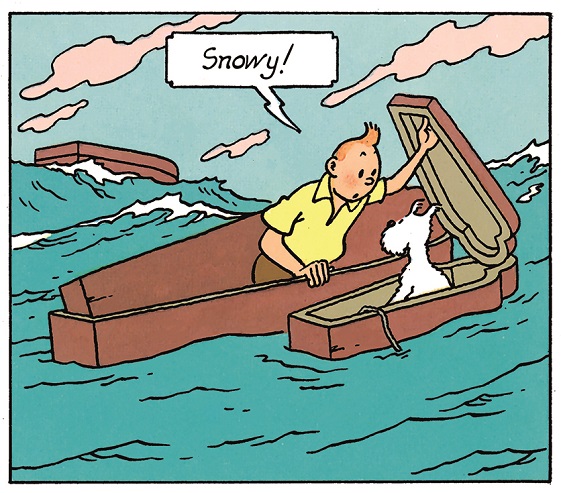

The comic strip, which would later become the book Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, was an instant success. Readers lapped up the stories of Tintin's adventures, which Hergé filled with a quick wit and rich personalities – not least, Tintin’s astute and faithful fox terrier Milou (Snowy in English).

They were illustrated in a style that Hergé pioneered called ligne claire, or clear line: simple lines of almost uniform thickness, with no shading. His technique, which created an uncluttered image with robust, universal elements, gave his work a distinct visual style and influenced cartoonists that followed, such as Asterix artist Uderzo, and the Smurfs' Peyo.

Hergé was also a master of pacing and narrative structure. He understood how to use the medium of comics to its fullest potential, creating stories that flowed seamlessly from panel to panel and page to page. His ability to craft complex plots and multi-layered characters remains a benchmark for the medium to this day.

Tintin was quickly dispatched to other hotspots of the time, from Al Capone's Chicago to Japanese-occupied China. The early books – Tintin in the Congo, Tintin in America, and Cigars of the Pharaoh – showcased Hergé’s talent for creating vivid, imaginative worlds.

Tintin and his friends travel far, encountering different cultures, languages, and customs along the way. Hergé was renowned for his meticulous research. Like Jules Verne, Hergé rarely left his desk, but he made his protagonist a world traveller, meeting cultures that his creator encountered only in books and magazines.

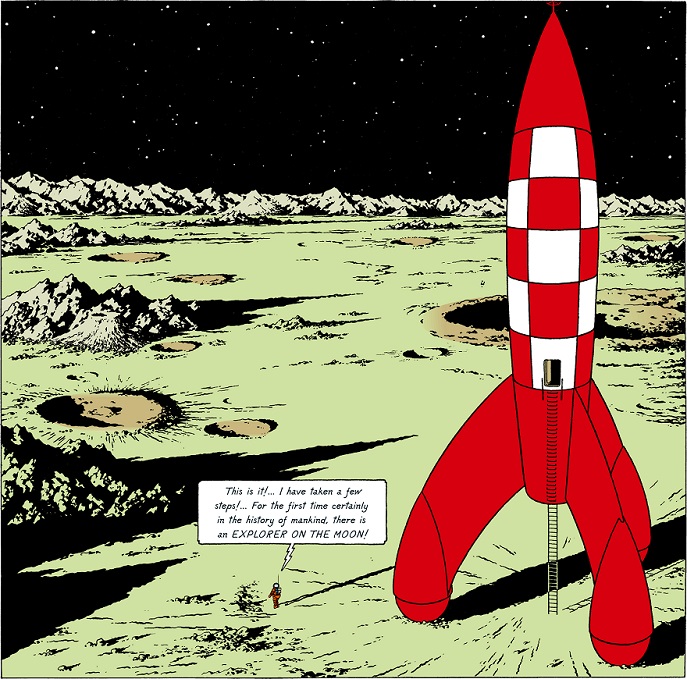

The iconic moon rocket

His dedication to accuracy was unparalleled, and he spent countless hours studying history, geography, and science to ensure that his stories were as realistic as possible. His attention to detail extended to every aspect of his work, from the clothing his characters wore to the architecture of the buildings they visited. For example, the rocket that takes Tintin to the Moon is meticulously drawn. The many vehicles Tintin uses – cars, planes, boats, trains and tanks – are exact representations of those of the time. And even scenes like the Incas in Prisoners of the Sun are taken from reliable sources like National Geographic magazine.

As for Tintin, he represents the ideal of the boyish hero: brave, resourceful, impeccably mannered and always willing to stand up for what is right. Whether he is battling evil villains, outwitting smugglers or simply exploring exotic lands, he is a figure readers can look up to and admire.

Tintin arriving at Marlinspike Hall, Haddock's family home

Hergé would launch other series too. In the 1930s, he created Quick and Flupke, about two scamps in the Marolles district of central Brussels, whose naughty nature contrasts with Tintin’s boy scout morals. He published five Jo, Zette and Jocko books about a brother, sister and pet chimpanzee. And the Hergé Studios would work for hire to produce advertisements. But it is Tintin for which Hergé remains synonymous.

Eternal and saintly

The Tintin comic strip and books would run for over half a century, but Hergé maintained that his hero was always just shy of his 18th birthday. He was notionally a reporter but never appears to have deadlines or editors. However, in the entire oeuvre, he is seen filing a report in just one frame. Still, with his seemingly limitless travel expenses, Tintin is sometimes seen as the patron saint of journalists.

Over the course of the books (Hergé would call them albums), Tintin accumulated friends. His retinue included cantankerous sailor Capitaine Haddock; eccentric egghead Professeur Tryphon Tournesol (Professor Calculus); the doltish, bowler-hatted, doppelgänger detectives, Dupont et Dupond (Thomson and Thompson); and overbearing opera diva Bianca Castafiore. And his adventures took on more elaborate themes, from drug smuggling to Cold War spying and even space travel. Tintin reached the moon 15 years before Neil Armstrong.

Scene from The Castafiore Emerald

The storytelling would evolve throughout the books. Early Tintin strips were marked by a simple, cartoonish style and a sometimes-rough humour. These stories were often episodic, with Tintin moving from one adventure to the next without much in the way of an overarching plot.

But as Hergé honed his craft the stories became more elaborate. He began to weave together longer, more complex narratives, with multiple plot threads and recurring characters. At the same time, Hergé's use of line and colour became more subtle and expressive, creating a sense of depth and atmosphere that set Tintin apart from other comic book heroes of the time. While his initial strips were black-and-white, he soon moved on to colour. And over time, he – or his studio, which he later founded – would redraw entire books (The Black Island would even be redrawn twice).

Panel from Cigars of the Pharaoh

Though exotic, the Tintin universe is also a deeply human one. The characters are complex and flawed, with their hopes, fears, and desires. Tintin himself is a stoic figure, but he is also capable of moments of vulnerability and doubt.

Caricatures and redemption

For all their popularity, the Tintin stories are not without controversy. Some critics have accused Hergé of racism and cultural insensitivity, pointing to elements of the early stories, such as the caricatured depictions of African tribespeople in Tintin in the Congo (although this book is particularly popular in Africa).

The hardline politics of Le Vingtième Siècle and Wallez would rub off on early Tintin adventures. In The Shooting Star, for example, the main villain is a greed-driven, big-nosed Jewish businessman (he would be changed in later editions). They rubbed off on Hergé too. He drew the cover for a 1930s political pamphlet for Léon Degrelle, leader of the Belgian fascists. Degrelle claimed he was the inspiration for Tintin, but Hergé virulently denied this.

Hergé was later arrested for being a wartime collaborator as he had continued to draw cartoons for the Le Soir newspaper, which was controlled by the Nazi occupiers during the Second World War. He spent a night in prison, but his file was eventually closed without legal action. Still, rumours and insinuations followed him for the rest of his life, and he had frequent bouts of depression.

It wasn't until later in his career that Hergé began to acknowledge and address some of the problems in his earlier work. He was contrite about Tintin in The Congo, which was never published in English during his lifetime. In later books, Tintin is found fighting both communists and capitalists and by the 1970s he had replaced his cloth cap and plus fours with blue jeans and yoga.

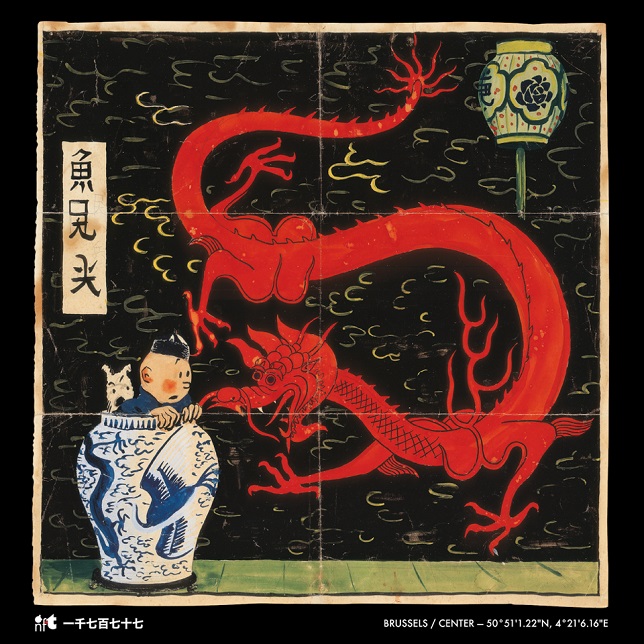

Hergé's unused picture from The Bleu Lotus

Hergé's favourite story was the 1960 Tintin in Tibet, which tells of Tintin's search for a Chinese boy, Chang (based on one of Hergé's closest friends), whose plane crashes in the Himalayas. In 2006, the Dalai Lama himself awarded a 'Truth of Light' award to the Hergé Foundation, which runs the late author's estate, as a gesture of thanks.

Hergé would also help nurture the comic arts. In 1946, he launched a magazine, the Journal de Tintin, which would compete with Spirou as a showcase for emerging comic strips, as well as for serialising Tintin stories.

Afterlife

Hergé died in 1983 shortly after starting a new book - Tintin and Alph-Art, about a conspiracy involving modern art and a religious cult. It is unclear where the plot would go as Hergé had only sketched a few pages – and he expressly said the Tintin series would end with his passing.

The initial years after Hergé’s death saw the Tintin organisation struggle to adjust, but it eventually found its way. The books were adapted into a successful animated television series in the 1990s. And when it came to merchandising, the Tintin brand would be pitched at the high end of the market, with only a limited number of tie-in products sold at a few stores, like the Tintin shop next to the Grand Place. Today, the Hergé Foundation even winces at describing Tintin as a comic strip, suggesting it is something more artful and distinct.

Still, as Tintin approaches his centenary, his popularity shows no sign of waning. His 23 completed books published between 1929 and 1976 are thought to have sold more than 250 million copies worldwide (the Hergé Foundation refuses to reveal exact figures). Nor is the Tintin industry about to rest on its laurels, as it prepares to update its offerings for the next generation.

The first big step took place in 2007 when the €20 million Hergé Museum opened in Louvain-La-Neuve, some 32 km southeast of Brussels. Financed by Hergé's second wife Fanny, it is a stunning piece of architecture: its sleek concrete, steel and glass evoke the forms of an ocean liner, deliberately echoing Tintin's many maritime exploits.

The Hergé Museum, Louvain-la-Neuve

In 2011, Tinseltown took on Tintin: Hollywood royalty Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson teamed up for The Adventures of Tintin, a computer-animated movie that mixes parts of the books with new elements. The film was the culmination of a decades-long mission for Spielberg, who first bought an option to film the character just before Hergé’s death (elements of Tintin can be nonetheless seen in Spielberg’s Indiana Jones films).

In recent years, there have been Tintin musicals, travelling exhibitions (including a recent immersive experience), colourised versions of the first black-and-white strips, new English translations (blistering barnacles and thundering typhoons are mercifully retained), and apps to provide a digital version of the books.

Belgium is also increasingly recognising Tintin as one of its greatest icons: he features on Belgian passports, his image is painted on Brussels Airlines planes, and a six-metre version of his Moon rocket stands in the departure lounge of Brussels Airport.

Last year, the Hergé Foundation changed its internal arrangements, creating Tintinimaginatio to run its licensing. The name reflects its ambition to venture further into digital, and earlier this year it announced a scheme for a non-fungible token (NFT).

The first NFT is an unused Hergé picture for the cover of the 1936 book The Blue Lotus, depicting Tintin and Snowy peeking out of a Ming-style vase and facing a menacing red Chinese dragon. The original picture was sold for a record €3.2 million at an auction in 2021, despite pleas from the Hergé Foundation that it had been stolen from the archives and should never have been put on the market. The NFT is thus partly a bid to reclaim the ownership of the image. It is also part of a broader effort to keep the Tintin brand fresh as the comic book era enters a new phase.

Time will tell whether these digital devices succeed. However, Tintin’s overall sway still seems strong. People continue to buy his books, with parents still reading them to their children, as their parents once did. His popularity has endured for almost a century, a testament to the lasting appeal of Hergé's storytelling and artistic vision. The world of comics would not be the same without him, and we are all the richer for having met this remarkable boy reporter and his intrepid creator