When I started out, no one wanted to do a comic strip that took place in Brussels. Artists did not want their characters to fit into a typically Brussels or Belgian universe, because most of the readers were French. The references had to be either Parisian or French in general. Belgian characteristics would be removed from the stories.

While Hergé's Quick and Flupke was a rare comic strip for a Belgian audience, his better-known Tintin albums made almost no reference to Belgium or Brussels. There are of course small details. When you look closely at the Tintin books you can see some are set in Brussels.

Similarly, Belgian artist Edgar P Jacobs set two Blake and Mortimer stories in Paris and one in London, but none in Brussels.

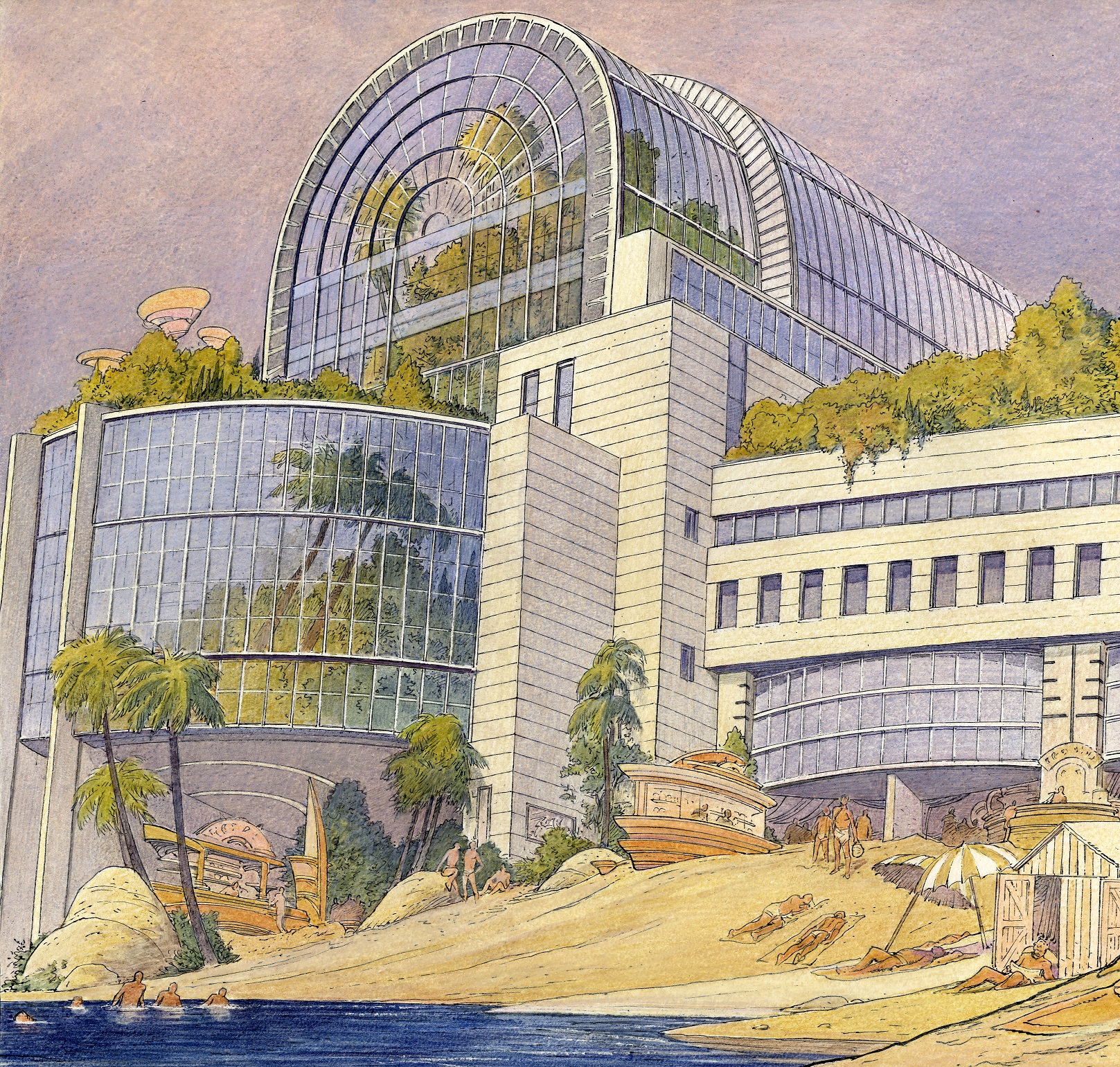

So when I suggested doing an album in Brussels, I was told, "You're crazy, you're going to cut yourself off from the French public." But today, Brüsel is our bestselling book.

I grew up in Woluwé-Saint-Lambert, close to Stockel, in what is now the ex-pat area. When I was 21, I settled in the heart of the capital. It is a contradictory city. It doesn't quite belong to Belgium. The Flemings don't like it, nor do the Walloons much either. And sometimes, even the people of Brussels don't seem to like it – although that is starting to change.

But it is a city that belongs to everyone, and that's what I like. It has character. People have a paradoxical love/hate relationship with Brussels, but this is also an opportunity.

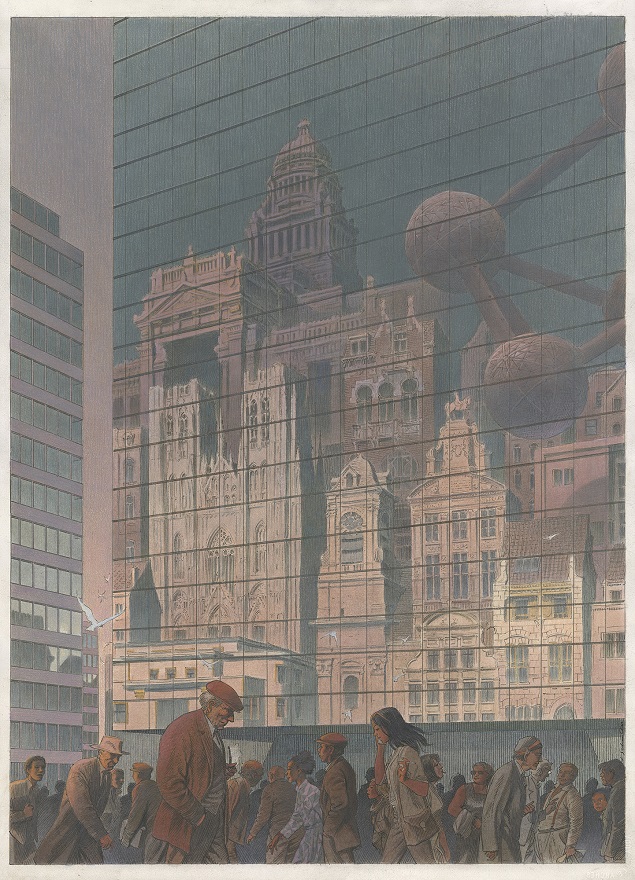

The city’s character is partly built on its Europeanness. We don't talk enough about its multicultural side, which makes it particularly conducive to the arts and to artists. Brussels is at the crossroads of languages and communities – and a melting pot for comic strips. It's a city marked by cultures, by trains and planes that don't stop, and by people passing through.

The city's transient nature means it does not always command respect – but that has advantages too. It is caught between powerful currents, which gives it vibrancy. We do not hear the deafening noise of national culture, as you do in Paris, where it's French culture, or in London, where it's English culture. Brussels looks at what is around, picking up ideas from different corners.

Atlantic influence

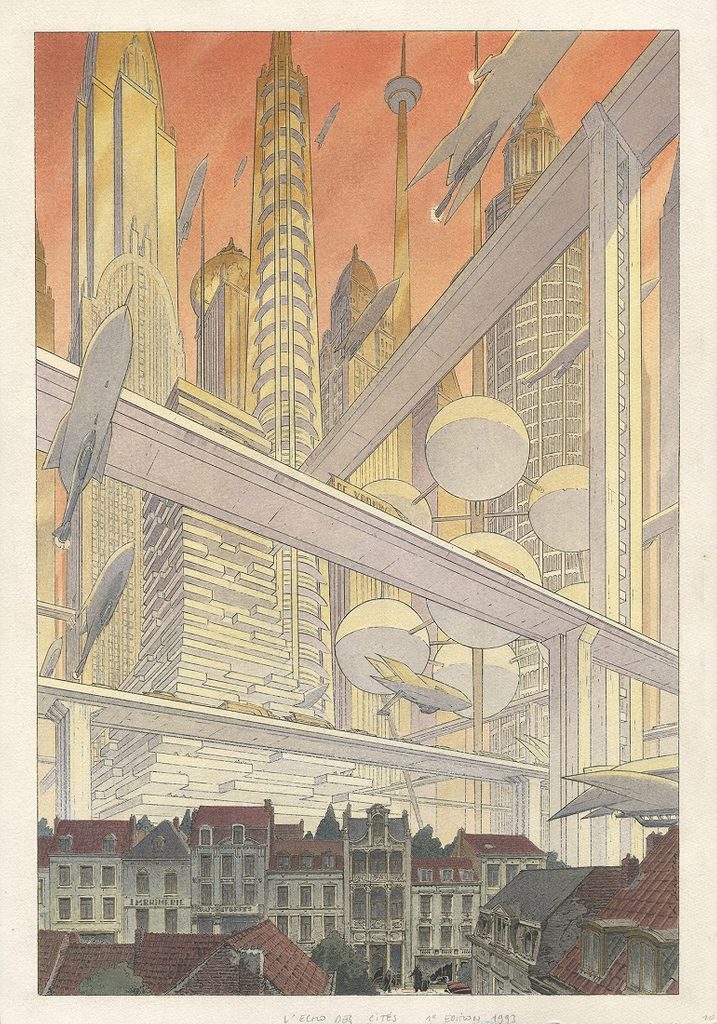

Of course, the contrast with French comic strips is not the only way that we are distinct. The big reference point is America, with Disney, and then later Batman, Superman and the Marvel comics. Before that, there were great American cartoonists and animators like Winsor McCay, Milton Caniff and Hal Foster.

When we talk about comic strip traditions, for me, the Americans are the ones who built the bomb. That's where it was created because their newspapers published these authors at scale and in colour, authentically rendering the language of comics.

We followed. I recently gave my partner an original edition of Little Sammy Sneeze, a masterpiece by Windsor McKay, published in France in 1905, which is a very beautiful book. It seems so modern: the beautiful cover, the lines, the speech bubbles, everything. The American authors had a real vision. We only came later.

What are the defining characteristics and traits of Belgian comics? In the golden age, the authors that I admire – Hergé, Franquin and Jacobs – flourished here in large part thanks to publishers. We needed publishers like Dupuis, Casterman and later Lombard. They had a real vision of what they could do. They encouraged authors to put their souls into their comics. Hergé puts his life into it: that's all he thought about. He didn't have children, and neither did Jacobs. There is force, spirit, a generosity in their work which is almost unbelievable.

Of course, there is humour. Humour is integral to the Brussels identity, especially irony. Belgians know that as a small, fragile country, we can't afford to be arrogant. We know our position is precarious. That sense of peril affects our outlook.

And there is also a fantastical side. This is in our country's imaginative roots, which comes across in painting, literature and comics. For example, the likes of Suske and Wiske in Flanders are connected to the more bizarre imagery of Bruegel.

And finally, there is ambition: grand – but also grounded – aspirations. Not taking yourself too seriously but taking your job seriously.

Schools for scoundrels

Alas, Belgian comics are no longer the force they once were. We had an amazing run. Before the war there was Hergé, and then after the war, when we made masterpieces for a decade, when everyone came here, including Goscinny and Uderzo, the creators of Asterix. We had an exceptional moment: that rare time when a country or a city shines.

But afterwards, it slowly went downhill. While there is still some great art in Belgium, the concentration of authors of genius has shrunk. The Tintin and Spirou magazines lost some of their strength. The centre of gravity moved to Paris, Italy, and Spain – not to mention Japan, where manga exploded. Comic strips today are global.

And the sector is going through a very difficult period. It's tough for young people who start today to live from drawing and writing comics. We are overproducing, and it is weakening the profession. When I started in the early 1980s, there were around 300 new releases a year. Now the number is around 5,500 – but the readership has not grown along with the titles. It is overloaded, and it is harder for good authors and artists to emerge.

The books also only stay a short time in bookstores: there is a very fast turnover which also hurts the trade. It's why I stopped. I can't spend three years on a comic book anymore – it doesn't work.

There are still many students who come here from around the world to study at places like the Institut Saint-Luc, which was the first daytime comic book school in Brussels. I passed through the school, like a lot of my friends who became professionals. And comics are a great teacher for young artists to learn to tell, draw, and layout effectively. It's a very good launchpad to go into video games or animation. So, I'm not too worried about talented people who advance their careers through comics.

I feel proud looking back at the history of Belgian comics. We don't talk enough about pride: it's a somewhat forgotten feeling. I looked at the issue of pride in my book, La Douce, about train drivers and engineers. I thought it was important to restore pride to all those who worked in the railway industry.

We forget that pride helps build the desire to live and to do a job. It helps me to know that I had authors like Jacobs, Hergé and Franquin as 'fathers', whom I admire just as much today as I did when I started. When I made the Le Dernier Pharaon in 2019, as a special Blake and Mortimer album, it was a tribute to Jacobs. There is a sense of pride in knowing that I am part of this family.

The golden age of Belgian – and in particular Brussels - comic strips may have passed, but the authors and artists who helped put us on the map are still inspiring.