In November 1792, ships laden with priceless art left the Habsburg Netherlands in a hurry. At the same time, the art collectors – Maria-Christina of Habsburg and Albert Casimir of Sachsen-Teschen – were fleeing Brussels in a carriage headed for Vienna. Since 1780, they had ruled the Habsburg Netherlands, or Austrian Netherlands – a terrain comprising most of modern-day Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands.

Why was this illustrious couple hitting the road? Because French revolutionary troops were busy defeating Habsburg troops 80km down the road at Jemappes. And though fortunes were briefly reversed at the Battle of Neerwinden in 1793, the Hapsburg troops were comprehensively pushed out in 1794 by the returning French army.

The French seized control of the territory, effectively ending the Hapsburg rule from Vienna. But the Parisian overlords were initially unsure what to do with their newly-conquered land (as well as the Habsburg Netherlands, they also took the Prince-Bishopric of Liège). Some felt an independent Belgian republic should be set up, in line with the revolutionary mantra of liberty. But in 1795, they decided instead to annex the whole area into the French Republic.

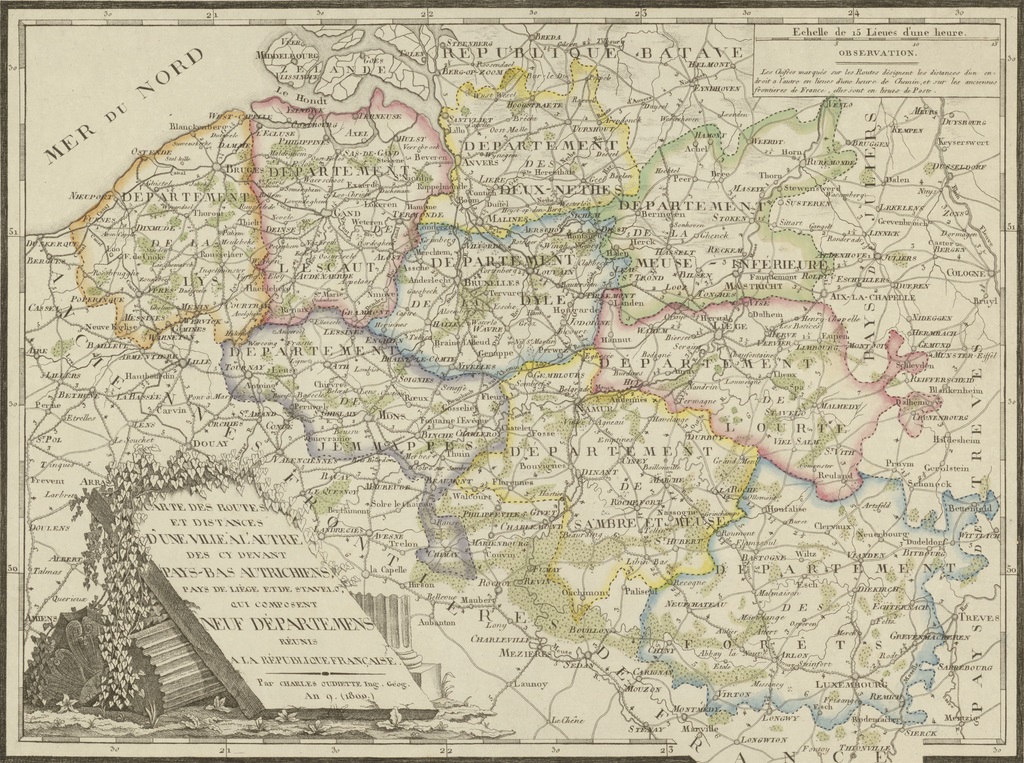

Ancient 1,000-year-old entities, such as the County of Flanders, Duchy of Brabant, and County of Hainaut, ceased to exist as the land was reorganised into ‘United Departments’. Institutions that had run the land since the Middle Ages, ranging from courts of justice to the office of bailiff, vanished – along with old borders – into thin French air. Even the University of Leuven, founded in 1425, closed its doors.

Department names excluded old-school references like Flanders, Brabant, Namur or Hainaut, and acquired shiny new monikers such as Leie and Dijle (the latter claimed Brussels as its capital). This new chapter was embraced by some supporters of revolutionary ideals, and opposed by others who felt their traditions undermined.

Map of the Nine Departments by Charles Oudiette, 1880

The Catholic Church was also made painfully aware of the new master in town. Priests refusing to swear allegiance to the new regime were prosecuted, abbeys were dissolved, and French authorities declared various buildings national property, often resulting in the destruction or public sale of entire churches. The ancient St. Donatian’s Cathedral of Bruges was expropriated and stripped, and its parts sold to the highest bidder, from stained glass and bells to funeral monuments. Gradually schools too, traditionally church-run, became state-owned.

These impositions were already being met with grumbles by locals when the French legislator, the so-called Council of Five Hundred, went even further, enforcing compulsory military service.

Pockets of resistance were formed, mainly from poorer communities. Town halls were sacked, civil registries destroyed, and many others attempted to hide from the draft. Isolated incidents cohered into a widespread revolt known as the Peasants’ War, which involved failed attempts to retake cities like Mechelen.

Episode from the Peasants' War by Theophile Lybaert

By December 1798 it was all over with the rebel army defeated at Hasselt. Some 1,000 people reportedly died and brutal repression followed. Around 200 people were executed and many more were arrested and shipped off. The French held firm grip on the land now.

Bonaparte in Brussels

It used to be said that when it rains in Paris, it drizzles in Brussels, a line referring to the sway that French politics held in Belgium. In 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte seized control of France, creating the French Consulate. He saw lots of potential in the lowlands and paid several visits to what were known as the Nine Departments. Antwerp was said to be “a loaded gun” aimed at Britain, and Napoleon ordered massive works to expand its port. The Bonaparte Dock remains to this day.

A year before taking power, Napoleon and his wife had visited Brussels, taking in the Manneken Pis and a performance at the Monnaie Theatre. Around 1,000 guests squeezed into Brussels Town Hall for his return in 1804.

During one trip the Simons family, providers of carriages to European royalty, offered some wheels as a gift. Impressed by the quality he ordered a dozen more, of which one wound up on Waterloo battlefield in 1815. Another favoured Belgian knick-knack was a zinc-lined bath from a Liège inventor.

With an eye for real estate, Napoleon spotted the old Schoonenberg Castle near Brussels, commissioned in the 1780s by the Habsburg rulers. Abandoned since its occupants fled, Napoleon bought it in 1804 for 500,000 francs. A massive revamp recreated a royal – and later imperial – residence. He stayed there twice, before gifting it in 1812 to Josephine de Beauharnais, although his ex-wife never made it there.

The same digs – now the Royal Castle of Laeken – have been the Belgian royal residence since 1831. Guests can still sit on the same chairs commissioned by Napoleon.

The Emperor also took a pied-à-terre in Antwerp but never stayed in the Meir-side mansion that he transformed into a grand palace.

Napoleon’s lasting legacy is the Napoleonic Code, still the core of Belgium’s civil legislation. But other trappings of power were less durable. After the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, Napoleon’s hold began to crumble, and in 1814 he was forced to abdicate and exiled to the island of Elba.

He returned in 1815, but his 100 days back in power ended in a final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo. Some 4,000 Belgians fought in the French army in the battle, against the same number on the allied side.

After Waterloo, the great powers decreed that today’s Belgium, the former Austrian Netherlands, would became part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. The short-lived French era was over, superseded by an even shorter Dutch one – the Belgian Revolution would take place in 1830. But the wheels of history kept turning. Victor-Napoleon Bonaparte would later marry Belgian Princess Clementine, daughter of King Leopold II.

Though the French era only lasted two decades, it had a profound impact on Belgium. Many provincial and local borders date to then, while the government was transformed by French principles.

And Belgium would not be Belgium if there was no sugar involved: a popular sour sweet was created in 1912 and named after Napoleon. The Bonbon Napoleon or Napoleon Canon is now very much part of Belgian culture.