This Prins family’s ties to jazz are a quintessentially Brussels story: their intergenerational involvement in the music both mirrors and nurtures the genre’s links to the city. Family members would not have met, would not have fallen in love and would not have created their music businesses if not for jazz – and the world of Belgian jazz would be poorer without their contribution.

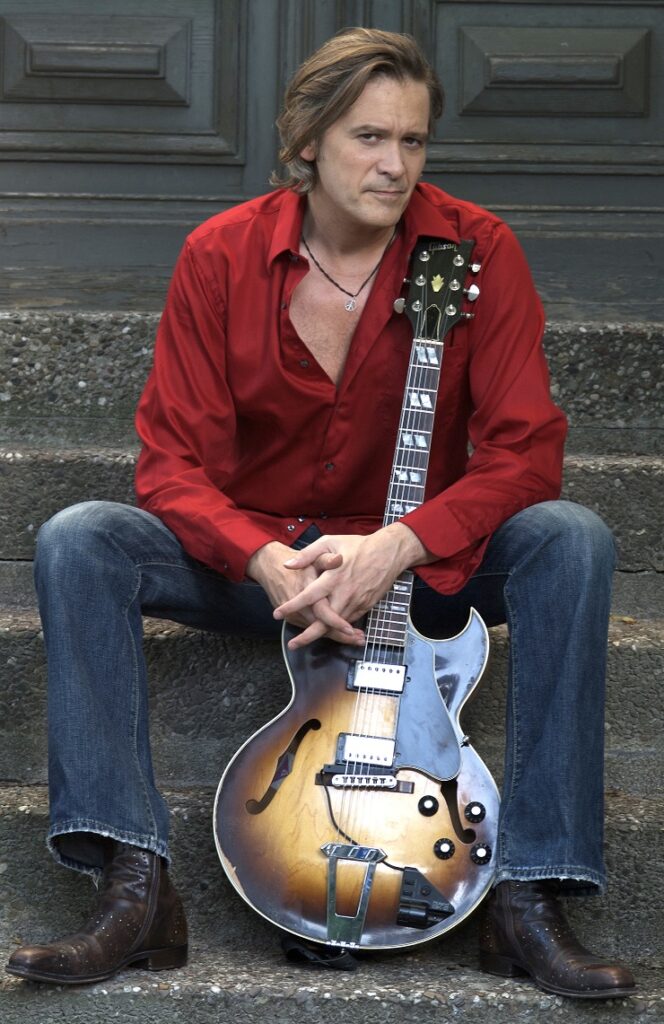

The current head of the family is Jeanfrançois Prins, 56, a musician, composer, and the director of GAM Records, an independent record company that specialises in jazz. He is the third generation of the family that has produced and promoted jazz in Brussels since the 1940s.

Brussels has been a jazz mecca almost since the sounds first emerged in New Orleans in the late 19th century. Different threads wove together to create the city’s jazz tapestry.

The saxophone was invented in Belgium and the first internationally acclaimed European jazz musician was a Belgian Romani named Django Reinhardt. Impresario Léopold Lenders, known as Pol, opened a half dozen jazz clubs over the years that headlined the biggest names in American jazz and blues.

Jeanfrançois Prins lists another factor. “Belgium is in the centre of Europe and has been invaded by everyone and their cousins for thousands of years,” he says. “We have influences from everywhere. We are a melting pot here, a little bit like the US where jazz was created. We perhaps have a more organic understanding of what it means to come from different backgrounds and try to create a federating language.”

He also points to Belgian lawyer Robert Goffin, whose 1932 book, Aux Frontières du Jazz, was the first to treat jazz seriously as an art form. “He was a fascinating guy who was a lawyer for lost causes and a close personal friend of Louis Armstrong,” Prins says.

Jeanfrançois Prins

Prins adds that Belgium was the first country, even before the US to appreciate that jazz was not just entertainment, but an art form and an invitation to musicians. Many American musicians who enlisted in the US armed forces or signed up during both world wars found themselves in Belgium, and they were warmly welcomed after the hostilities ended. They played their music and “people were immediately in love with the freedom that that music represented,” Prins says.

Brussels still boasts venerable but vibrant jazz venues and hosts festivals all year round: Brussels Jazz Festival, Brussels Jazz Weekend, Marni Jazz Festival, Saint-Jazz Festival, River Jazz Festival and Jazz Jette June, to name just a few.

Family affair

Prins’s grandfather, Ward Prins, was an amateur musician and a record producer, working with both big bands and unknown local talents, nurturing young musicians and organising concerts, and even playing a role in the Belgian Resistance, hiding people in his home and his record store during the occupation.. “He had a real love for jazz and a real understanding for that music,” Prins says.

“In 1942 he recorded what became famous recordings of Django Rheinhardt with the Stan Brenders Big Band. He also recorded the only recordings that Django did on the violin.” As a Romani, or ‘manouche’, Rheinhardt had to be wary of the Gestapo during the occupation. “He was caught, but thank God, he was arrested by German officers who were big fans of his music and released him, twice!” Prins says.

Django Rheinhardt

Prins’s father, Jeanpierre Prins. practically grew up in the studio meeting the musicians and learning how to produce music but when he was 16, he had to start earning a living by any means possible because his father died young, soon after going bankrupt. So the elder Prins started working in a record factory. “He was actually physically making the records, putting the matter onto the master and transforming it into a disc and then carrying the boxes and doing everything, putting the covers on, everything. Our family has really covered every aspect of the record business,” says Jeanfrançois.

Jeanpierre Prins, who died four years ago, eventually became a salesperson and then manager of record stores and met his future wife Annemarie when she came in to pick up a record order. She began working in one of the stores after which she started her store, the Music Inn in Uccle which became internationally renowned for the breadth of its offers of jazz and classical music.

Jeanfrançois Prins and his mother

“You could go in and sing any kind of melody and she would recognise it immediately,” Jeanfrançois says. “She would tell you ‘Oh yeah that’s the second movement of Brahms’ third symphony” and then she would propose four or five different versions that you could choose from. That was really her passion. She loved all kinds of music: hers was the first store in Belgium to have records by Dire Straits or Pink Floyd as well as original traditional music from India, from Africa, from Brazil, from everywhere.”

Frustrated by a lack of exposure for upcoming musicians, Annemarie created her own record label in 1991, which is how GAM Records came about. Now 85, she still comes to Jeanfrançois’s Belgian concerts.

Transatlantic links

Jeanfrançois became the label’s musical director, despite not playing an instrument until he was almost 20. However, he had spent four years studying music theory at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels and later graduated as a sound engineer. He has also taught jazz guitar at both the Universität der Kunst Berlin and the Jazz Institut Berlin.

At the same time, Jeanfrançois began dividing his time between Brussels and New York. He has continued recording, and his upcoming album, “Blue Note Mode”, was recorded in the Rudy Van Gelder studio in New Jersey where jazz giants of the 1950s to 70s would lay down tracks. “New York was always extremely important for me, my favourite scene, and the place where my two mentors Toots Thielemans and Lee Konitz lived,” he says. “I spent all my free time in New York, recording and producing there.” He has just recorded a new album there, which GAM Records has released.

Since moving back to Brussels in 2016, Jeanfrançois has reinvigorated the record label and made it even more eclectic, going beyond its origins in jazz and classical music. “For instance, I was approached by a pianist from France who plays music for documentary films, a lot of it underwater. It’s like new age music with classical sounds and jazz sounds but with a lot of space, meditative kind of stuff,” he says. “So, I started this ‘Beyond’ category. There’s a lot of other stuff that should be heard more, that is neither/nor, that kind of fits in between or is very different.”