While Belgium is one of the few remaining countries where turning up to vote is compulsory, around 10% of the population still stays at home during elections. But why does this obligation exist in the first place, and what would happen if it were abolished?

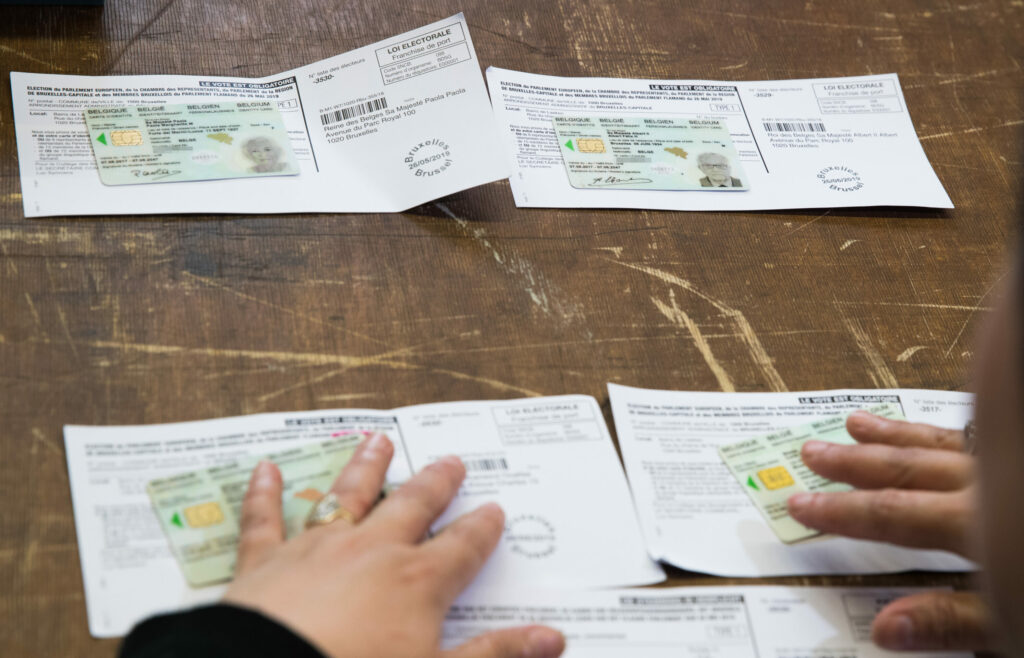

In Belgium, there is technically no compulsory voting, but there is compulsory attendance. In practice, this means that adults are obliged to go to the polling station on election day with their registration letter and identity card, but whether they cast a valid, invalid or blank vote is up to them.

In 2019, more than one million Belgians (nearly 10% of the country's population) refused to vote and did so either by not showing up at all or by casting a blank vote or an invalid one. Officially, people who do not go to vote risk a penalty of €40 up to €80, but in practice, people seldom get fined.

"I have never voted in my life. Whether it was the Christian democrats, the socialists or the Flemish nationalists who won the elections, nothing significant has changed over the past 40 years," one Belgian citizen (59) told The Brussels Times. "As if my vote is going to make a difference."

Credit: Belga / Hatim Kaghat

Despite the obligation to attend the elections, he has never received a reprimand or warning, or even so much as an acknowledgement from the authorities that his absence was registered.

"I know many people who don't go to vote. I don't understand why they make it mandatory. When all these different parties have to find a coalition agreement, everything gets watered down. It does not matter who heads the government, they do what they want anyway."

This year, a new political party called "Blanco" is running in the Federal elections aiming to capture this popular dissatisfaction. Aiming to embody the "protest vote", the party wants to be an option for those who do not see themselves represented by the current parties, and have refused to vote in previous elections – either by casting a blank or invalid vote, or by not showing up at all.

Their one and only campaigning point is to add an amendment to the Belgian constitution allowing empty seats in the Federal Parliament, which would represent the hundreds of thousands of people who did not vote for one of the parties on the ballot.

How did obligatory voting come about?

For the first several decades of Belgium's existence, voting operated on a tax-based system, whereby only men hailing from a certain financial bracket had the right to cast a ballot.

This changed in 1893 with the introduction of suffrage for men aged 25 and over. The system would still be considered unfair today as some men had more votes than others based on financial and other criteria (not to mention that women still didn’t have suffrage).

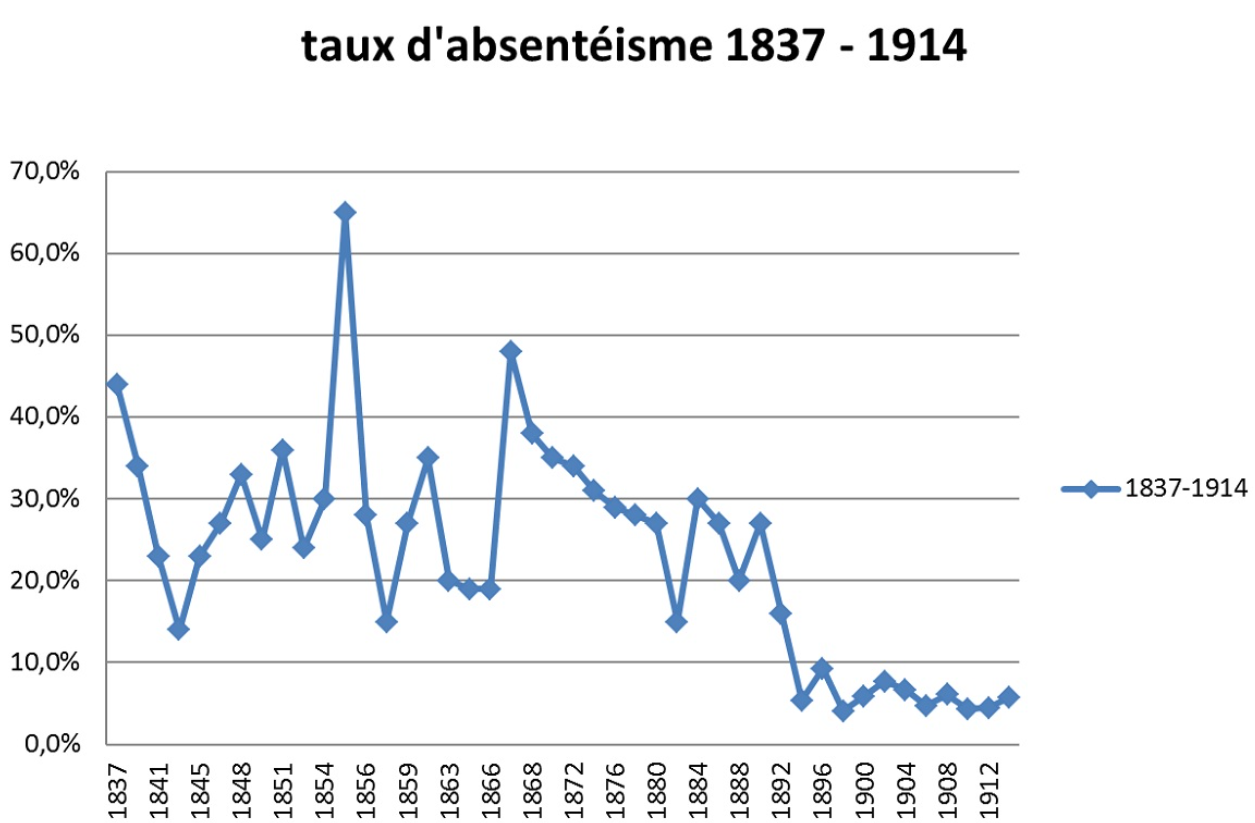

Nevertheless, the evolving system gave way to a new political party: the Belgian Labour Party (POB). Fearing its new opponent, the dominant Catholic Party introduced obligatory voting as a way to retain its privileged voter base, whose attendance had been waning steadily for quite some time.

Rate of absenteeism before and after the introduction of obligatory voting. Credit: the Senate

The introduction of obligatory voting was therefore more for strategic gain than it was for democratic values. The Catholic Party managed to enjoy a political majority until the outbreak of World War One in 1914.

This historical opportunism is reminiscent of the debate surrounding obligatory voting today, with parties likely to benefit from relaxed rules campaigning for its abolition.

What if voting was no longer compulsory?

For the first time in the Belgian system, people in Flanders will no longer be required to attend local elections in October – a decision that numerous political experts warned against, even calling it a "historic mistake" which would lead to many people with a less favourable socioeconomic position to not vote.

According to the results of the 'De Stemming', an opinion poll conducted by De Standaard and VRT in cooperation with the VUB and UAntwerp universities, 30% of surveyed Flemish people indicated that they would "definitely not" or "probably not" vote in the local elections in October – making a significant decline in turnout a real possibility.

For the regional, federal and European elections in June, turning up to vote remains mandatory. However, should Belgium decide to abolish compulsory attendance for the federal elections, around one in five people would "never" vote again, they indicated.

Belgium's former King Albert II and Queen Paola identity card taken to vote in Laeken, Sunday 26 May 2019. Credit: Belga/Benoit Doppagne

This group is largest among the Flemish far-right Vlaams Belang voters: 20% would never again vote for the Federal Parliament and 25% would no longer do so for the European Parliament. At the same time, Vlaams Belang also has a higher-than-average group (54%) that would "always" continue to vote faithfully.

Most doubters are on the left: the Belgian Workers Party PVDA-PTB (13%) and the Flemish socialists Vooruit (13%) would have the most to lose from an abolition of compulsory attendance. For the conservative nationalists N-VA (9%), liberal Open VLD (9%) and Groen (8%), doing away with the obligation would be somewhat less dramatic.

The Flemish Christian Democrats (CD&V), however, can seemingly sleep soundly: barely 1% of its voters indicated that they would "never" vote in the federal elections again, while as many as 66% would "always" continue to vote. Apart from CD&V, Vlaams Belang and Vooruit (57%), just under half of voters for all parties indicated that they would "always" continue to vote.

Capturing political dissatisfaction

The most striking observation remains the large difference in voting behaviour between people with different incomes: of the low-income group, 22% would never vote in the federal elections again, compared to 13% of the high-income group.

Conversely, 57% of high-income earners would always vote, compared to just 33% of low-income earners. "And that is also the main reason why very few political scientists think the abolition of compulsory attendance is a good idea," said researcher Stefaan Walgrave (UAntwerpen).

The researchers also found that even people who do not plan to vote or do not yet know whether they will vote, "are not as dissatisfied as Vlaams Belang voters." The same goes for first-time voters (the young people who will soon vote for the first time): they are more satisfied than the voters of Vlaams Belang.

"It is very clear that Vlaams Belang, more than any other party, captures political dissatisfaction," Walgrave said. "With that party, the rejection of the political system is virtually absolute and universal. At the moment, it is difficult to imagine that the Vlaams Belang electorate would be charmed by one of the other parties."