On this day, 8 August 1956, an accident at the Bois du Cazier coal mine in Marcinelle, Charleroi, triggered a devastating fire that took the lives of 262 miners, leaving only 13 survivors. More than half of the victims were Italian.

67 years ago to the day, 975 metres below the surface of the earth, a worker initiated the hoisting mechanism of a coal elevator. A wagon that should have been pushed out of the elevator cage became stuck. The cage nevertheless began to rise through the mine, and the wagon that was left sticking out damaged an oil pipe, two high-voltage electrical cables and a compressed-air pipe.

A fire ignited, further fuelled by the wooden infrastructure, then rampaged throughout the rest of the mine. The coal extraction shaft, where the fire started, was also the only passageway for air intake into the mine. A poisonous cloud of smoke and carbon monoxide immediately infiltrated the ventilation system and poured into the galleries.

Soon after, seven workers, including the one who involuntarily started the fire, reached the surface. The billowing smoke immediately attracted attention, and crowds of curious onlookers and then terrified family members gathered to see what was happening.

Emergency services were quickly dispatched and many rescue missions attempted to reach the hundreds of miners still trapped within the burning mine. Six more men were rescued. The efforts continued for two weeks, during which families watched with anguish through the gates of the property. It was not until 23 August that emergency service workers were able to reach the lowest levels of the mine, at over one thousand metres in depth.

The communication sent back to the surface was in Italian, and tragically short: "Tutti cadaveri" – all corpses.

A crowd gathers outside the gates of the coal mine at Marcinelle on 8 August 1956. Credit: Belga Photo Archives

The ‘Men-for-coal’ agreement

The bodies of 262 miners were recovered weeks after the fire, and more than half were Italian miners. The origin of the immense population of Italian miners in Belgium can be traced back to the 'men-for-coal' agreement signed by Belgium and Italy in 1946.

During the Second World War and under German occupation, Polish and Russian prisoners were sent to work in the mines, and after Belgium was liberated, they were replaced with German prisoners. This was, all things considered, a convenient business model for the mines’ patrons, since prisoners were not paid.

But with the end of the war, all prisoners were repatriated, and Belgium needed to look elsewhere for a mining workforce. Belgians themselves were strongly unionised and aware of the horrific working conditions for miners. These mines could not count on the local population to fill their ranks, so Belgium looked outwards.

In Italy, there was political and social turmoil in the immediate post-war period, as well as rampant unemployment.

“Italy was very happy to get rid of young Italians looking for jobs that weren’t available, especially if they were anarchists, socialists, or communists,” explained Anne Morelli, Belgian-Italian historian and honorary professor at the Free University of Brussels (VUB). Italy also stood to gain economically from the exodus of men to Belgium, because they would be sending money to the families that had remained in Italy.

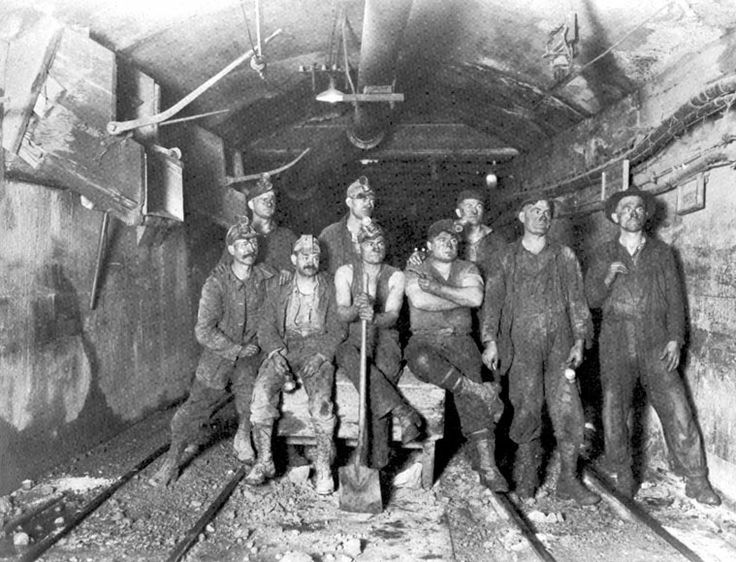

Italian miners working in Charleroi, 1950s.

And so Belgium and Italy signed the so-called "men-for-coal" agreement that facilitated the northbound immigration of thousands of Italian men in exchange for two to three million tonnes of Belgian coal a year at preferential rates.

Needless to say, the working and living conditions for Italian immigrants and their families were horrific.

“My father worked for 15 years straight in the mines, and then slowly fell ill. He grew weaker, and began to lose his breath. His health continued to decline throughout the seventies, and he had to frequently go to the hospital. At home he had an oxygen tank,” says Lorena Noé, daughter of an Italian miner and now head of the Marchigiana del Limburgo association since 2003, a cultural organisation that keeps the memory of Italian immigrants and miners in Belgium alive.

“My father worked for 15 years straight in the mines, and then slowly fell ill. He grew weaker, and began to lose his breath. His health continued to decline throughout the seventies, and he had to frequently go to the hospital. At home he had an oxygen tank,” says Lorena Noé, daughter of an Italian miner and now head of the Marchigiana del Limburgo association since 2003, a cultural organisation that keeps the memory of Italian immigrants and miners in Belgium alive.

“For us children it wasn’t easy hearing him cough all night, and it destroyed us to see that he couldn’t breathe,” she added. Noé’s father died at 60.

Funeral for the victims of the Marcinelle tragedy. Credit: Belga Photo Archives

The ‘comfortable’ concept of catastrophe

“People call the Marcinelle tragedy a catastrophe, which would make it like an earthquake or a volcanic eruption, meaning that there was nothing to do about it,” said Professor Morelli. “But Marcinelle was not a catastrophe because it was a foreshadowed disaster. There were safety regulations, but since the mine was about to be closed, the inspectors ignored them.”

It is well known that the electrical cables were dangerously close to oil pipes, and many of the miners were young and undertrained. The young man who triggered the fires at Marcinelle apparently regularly confused the signals of the carts.

“It was going to happen at some point,” the professor said. A book she edited called Retour sur Marcinelle also dispels the myth that the tragedy would lead to important changes in Belgian labour legislation for the health and safety of workers.

Colleagues of the victims at the funerals. Credit: Belga Photo Archives

The truth was that workers’ rights still had a long way to go. Illnesses like silicosis, for example, which is caused by years of inhaling silica dust, were not immediately recognised as an occupational disease despite how frequently it afflicted miners.

Even in the sixties, the working conditions for miners remained

Today, we remember the miners whose suffering culminated at 8:10 am on 8 August 1956, and those who continued to fight for their rights and memory in the aftermath of the tragedy.

"Today in History" is a new historical series brought to you by The Brussels Times, aiming to take you on a trip down memory lane for newcomers and Belgians alike. This entry was written by Margherita Bassi.