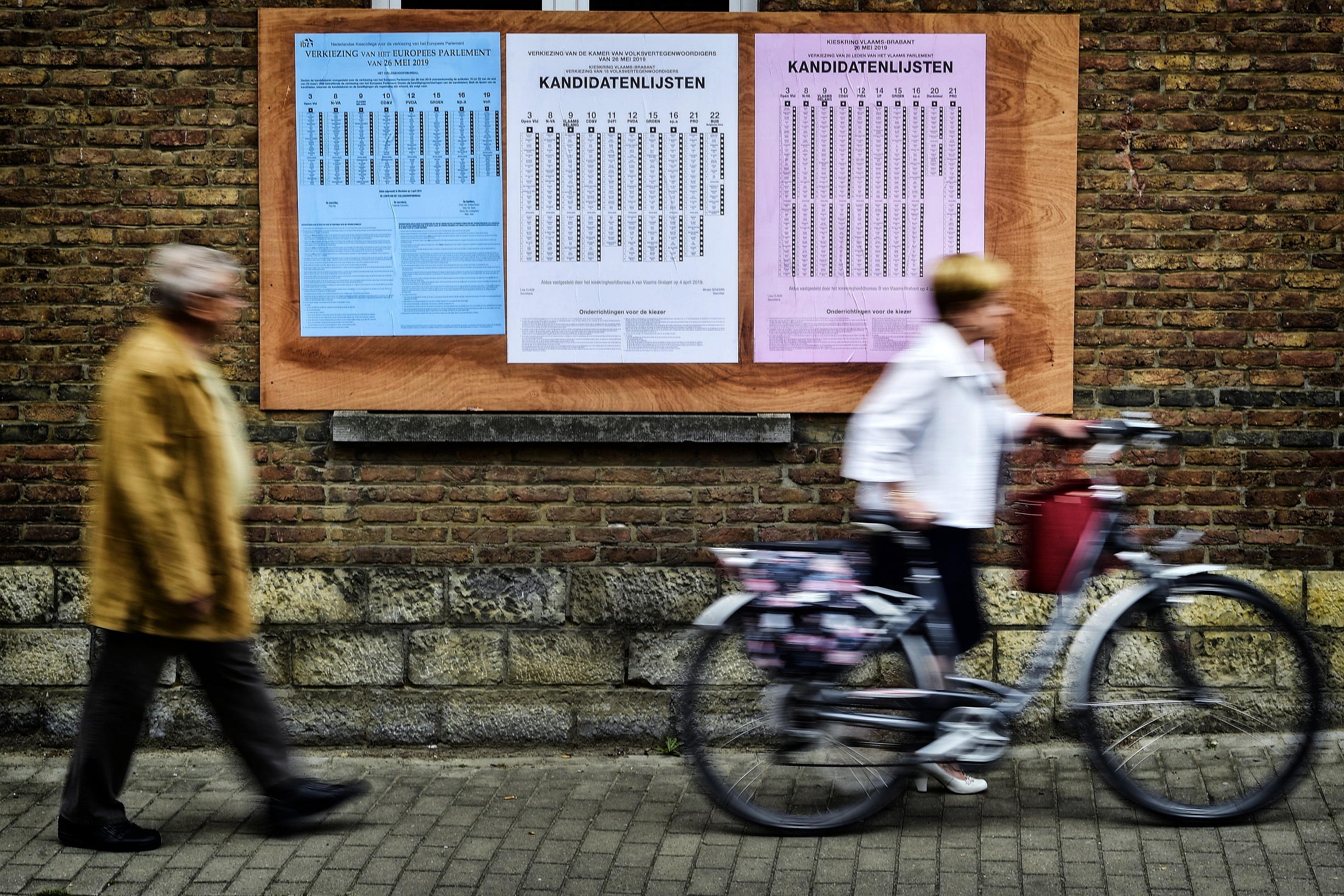

On June 9, Belgians will head to local schools and government buildings across the country to cast their vote in federal and regional elections, as well as European elections. And they’ll head back a few months later, along with thousands of eligible non-Belgians, to vote in local municipal elections.

They’re not the only ones to vote in 2024. This year, an estimated four billion people, roughly one-half of the world’s population, are voting in new governments across 70 countries. It’s predicted to be a testing year that could lead to a seismic shift in global politics.

The US elections on November 5 are likely to be the most dramatic that anyone has seen in a long time. But the European Parliament elections in early June could produce a nasty shock if, as most polls are predicting, extreme right-wing candidates gain more seats.

You might think that the Belgian elections are small fry compared to India, the US or the EU. It’s hard to imagine that the 150 MPs who sit down on the green leather benches in the Belgian Chamber of Representatives will have much of a say in what happens in Ukraine or Gaza or climate change talks.

And you might be particularly cynical if you don’t have a vote at all on June 9. Even if you do have a vote, it could strike you as a pointless exercise that won’t change anything. Many people complain that Belgium's political structure is too complicated. There are too many parliaments, too many politicians and too many different government departments.

There are in fact seven different parliaments. There’s the federal parliament facing the royal park in Brussels, the Flemish parliament in a street behind the federal parliament, the Wallonia parliament on the banks of the Meuse in Namur, the German region parliament in Eupen, the Brussels parliament just up the hill from the Manneken Pis and the French Community parliament opposite the royal park in Brussels.

You might well wonder what exactly you are voting for. The federal election will decide the seats in the federal parliament, along with the prime minister. The oldest parliament in Belgium decides how much tax you’re going to pay, how to fix the trains, and whether Belgium should appease a possible returning President Donald Trump by boosting its contribution to the NATO budget to 2% of GDP.

The regional elections involve issues that are closer to everyday life, like road construction, cycle lanes, air quality, school construction, rubbish collection and the environment. And the 581 municipalities get down to the gritty local issues, like policing, cleaning the streets, urban planning and the local economy.

Given the complexity, Belgians often have only a vague idea of the people who run the country. Not many would be able to name the speaker of the Flemish parliament (Liesbeth Homans), the president of the German parliament (Karl-Heinz Lambertz), the Walloon mobility minister (Philippe Henry) or the federal defence minister (Ludivine Dedonder). Just fix the potholes, you might want to shout.

Opening voting

When Belgium declared its independence in 1830, its founding fathers created a model constitution that defended basic human rights. But it took years of struggle to extend the vote to every Belgian. In the beginning, the vote was granted to a tiny minority of property-owning men, 46,000 out of a population of four million. The idea at the time was that you had to have a vested interest in the country (and be male) to vote correctly.

By the 1890s, as the workers’ movement grew in strength, the vote was extended to every male over the age of 25. After the First World War, a handful of women were allowed to vote – mainly those whose husbands had died in the fighting, or women who had fought in the resistance. But it wasn’t until 1948 that all Belgian women were put on the electoral register.

The struggle to extend the vote has continued in recent years with a campaign to allow non-Belgians to vote in municipal elections. This right was finally granted to EU citizens in 1999, although non-EU citizens must live in the local commune for six years to qualify. Ironically, given the long struggle to get the vote extended, only a small percentage of EU citizens choose to exercise the right (just 17% in the most recent election).

Voting booths, Ghent

Everyone agrees that Belgian elections are complicated. But maybe they are fair. The seats are allocated according to a method developed in 1899 by the Ghent University law professor Victor D’Hondt. He is not honoured anywhere with a statue, or a street name, but he created a formula of proportional representation that aims to match the number of seats to the share of votes.

The D’Hondt method has been copied by democracies across the world, including the Netherlands, Spain, Portugal, Japan and Argentina. It’s also the system used by many EU countries when they count up the votes in the European Parliament elections.

Compulsory voting is another Belgian peculiarity that deters many foreigners from registering to vote. It is based on the idea that parliament should reflect the will of the entire country. The result is a high turnout on polling day, a few spoiled ballot papers (around 7%), and a similar number who refuse to vote.

Language barriers

The next layer of complexity is due to language. The choice of parties is based on language, rather than policies. When you step into a polling booth in Flanders, you can only vote for Dutch-speaking parties, while over in Wallonia, the only parties that come up on the touch screen are French-speaking. Meanwhile, in bilingual Brussels, you have to choose the language list before casting a vote.

Polling station in Bastogne, Wallonia

This means the country has two different political systems. The French-speaking socialists of PS are normally more robustly leftist than the Dutch-speaking socialists of Vooruit. And the French-speaking liberal party MR doesn’t share the same values as the Flemish liberals of Open VLD. It means a voter in Antwerp doesn’t have the same choice as a voter in Liège. Critics say they might as well be living in different countries.

The Belgian system also allows voters to choose a preferred candidate from the party’s list. Normally, the party lists candidates in the order of importance within the party, so the first candidate on the list – normally the most popular – has the highest chance of becoming a member of parliament. However, the voters can influence the outcome if enough people express a preference for a particular candidate.

Then there’s the time it takes to form a government. Years, sometimes. Following elections in 2010, Belgium limped on without a government for 541 days, a world record in government formation. The same problem returned after the 2019 elections: they managed to cut down the time spent talking to 493 days.

As the 2010-11 negotiations dragged on, some women refused to have sex until the government was formed, while men refused to shave. And on the day when Belgium broke the world record (held up until then by Iraq), stallholders handed out free frites and beer. It was seen as absurd, not existential.

Observers from other countries, like the United States and Britain, are astonished that it can take so long. But the Belgian response is often relaxed. The slow formation in 2010 and 2019 only affected the federal government, people point out. The other six Belgian governments continued to function smoothly, so there was hardly any disruption. The only policy areas that were blocked were signing off a budget (so the country escaped austerity) and declaring war.

Different priorities

The big issues affecting voters this time round are likely to be migration (in Flanders) and the cost of living (in Wallonia and Brussels). With migration the key issue in Flanders, the anti-migrant Vlaams Belang (VB) is expected to emerge as the largest party. Meanwhile, voters in Wallonia who are struggling to pay the bills are set to vote in large numbers for the far-left coalition PVDA/PTB.

The formation of a Flemish government is expected to be more complicated this time because of VB gaining ground. In a poll carried out 100 days before the election, VB was on 28% of the Flemish vote, while the ruling party N-VA had slipped to 18%.

But forming a government means winning a majority of seats in the Flemish parliament which is only possible through a coalition. Most Flemish parties refuse to work with the far-right, apart from the centre-right N-VA. But even if the two right-wing parties joined forces, they would likely still fall below the 51% threshold needed to govern.

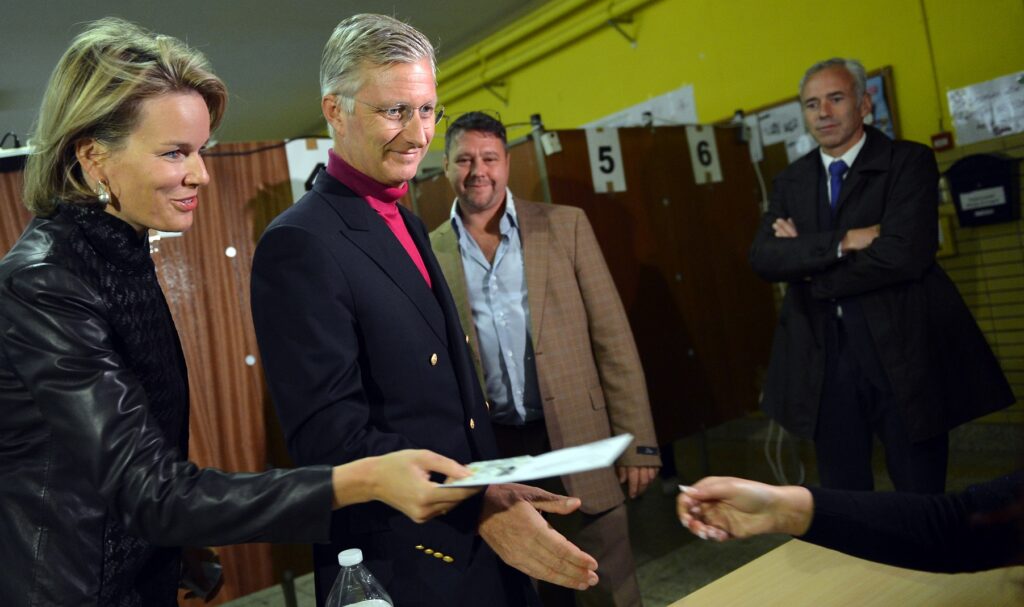

King and Queen of Belgium casting their votes in a previous election

Problems are looming at the federal level as well if VB emerges as the largest Flemish party. Under the rules, there has to be at least one Flemish and one Walloon party in government. The biggest Flemish party would be the obvious choice but none of the French-speaking parties would agree to join a government with VB. No pasarán. And so, we could face another long wait before a government is formed.

The same situation has emerged up north in the Netherlands. In the Dutch election last November, the far-right PVV party of Geert Wilders, came first, winning 37 seats. But Wilders struggled to find coalition partners to secure a majority in the 150-seat parliament: by mid-March, he abandoned his bid to become Dutch prime minister, complaining that the system was “unfair”.

The Belgian parties are already working on possible deals to boost their strength when it comes to forming a government. In Brussels, the Flemish liberals Open VLD are joining the French-speaking MR to present a common front. “We want to be unbeatable,” announced MR chief Georges-Louis Bouchez. Other parties are coming up with similar deals, which would leave the Flemish nationalists out in the cold, as there is no partner party on the other side of the language border.

Yes, it’s complicated in Belgium. Sometimes it works fine. Other times, it’s a mess. The recent rise in drug-related violence in Brussels showed how the many layers of government often fail to act decisively, as the mayor of Saint-Gilles commune (hit by a spate of shootings) blamed the minister-president of Brussels Region, who then argued it was the federal government that had to act.

You might end up feeling helpless. Will your compulsory visit to a polling booth make any difference? And yet sometimes a small country can be a global leader, and send a strong message. The federal government may have done that when it updated the criminal code recently to include the new crime of ecocide. When this law enters into force in 2026, Belgium will be the first country in the EU to make it an international crime to cause massive destruction of ecosystems.

The optimistic conclusion might be that a vote in Belgium does matter. But first, there has to be a government. And Belgium is unfortunately a world leader in slow democracy.