Belgium's monarchy are a familiar sight in national media and carry out many functions in the public eye. But what about the rest of Belgium's elite? Who are the nobles and what is their part in a fragmented country? And why are there two distinct types of aristocracy?

"Nobility" brings to mind stately manors, castles and elite balls (known as rallyes in Belgium). But Belgium's bourgeoisie is much more integrated into society than we might think, numbering around 35,000.

As in other European countries, nobility in Belgium is centuries-old. But the 1830 revolution through which Belgium gained its independence left a defining mark on the aristocracy, which remained intact – albeit in a different and diminished form, having lost its privileges and guaranteed representation in the États généraux (general assembly).

After gaining independence from the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Belgian revolutionaries debated whether or not to keep the aristocratic system established by William I. But a large majority were in favour of keeping it.

"What is most striking about this historical development is that the nobility still exists today," the President of the Nobility Council, Paul Janssens, told The Brussels Times. For the most part Europe’s elite disappeared during the 19th century, though Janssens points to England and post-Franco Spain (where nobility was re-established) as the exceptions. Germany and Austria both later abolished nobility after the First World War.

"As the power of royalty diminished in Europe, ennoblement – the King's power to appoint new nobles – also disappeared." Belgium is extraordinary in this respect.

The Nobility Association on Avenue Franklin Roosevelt in Brussels. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Janssens is a historian and has volunteered as a member of the Nobility Council for 40 years, which he considers "a political and institutional part of Belgium's cultural heritage."

The Nobility Department undertakes two main roles: firstly, it ensures that nobles receive the documents to which they are entitled (lettres de noblesse). This includes drawing up a diploma for new nobles, with their merits and achievements and a new coat of arms. This is presented by the King at the end of the year.

Secondly, it recognises (former) nobility. In 1830, almost all nobles lost their status following the revolution. The Council therefore had to recover their status and verify requests. "Today there are still cases, but increasingly fewer because most families have had their nobility recognised."

The select elite

Belgium sets itself apart from other countries with its "new" and "old" aristocracies: the pre-revolution hereditary nobles of the Ancien Régime and the modern-day nobles appointed each year by the King.

In 1830, the revolutionary republican liberals favoured maintaining the nobility, which they claimed didn't come with the same privileges of the Ancien Régime and prioritised legal equality of all citizens. Indeed, article 113 of the Belgian Constitution states: "The King may confer titles of nobility, without ever having the power to attach privileges to them."

Moreover, policy changes regarding nobility in 2018 ensured that new nobles were no longer granted hereditary titles but a personal title instead. "These have no influence in their companies or in national politics," Janssens stressed.

Queen Mathilde and King Philippe of Belgium and Marieke Vervoort pictured during the ceremony dedicated to people who received a nobility title in November 2013 at the Royal Palace in Brussels. Credit: Belga / Laurie Dieffembacq

Every year, the King selects around ten people to become members of the Belgian nobility. These are often already elites who have a prestigious career in business or in culture, or who have held important political positions. On this year's National Day, singer and rapper Stromae received the Order of the Crown for his artistic contributions.

But despite the revolutionaries' resolve to strip the titles of any privileges, "the modern nobility is obviously reminiscent of the Ancien Régime... When you talk about a baron, a count, a prince, a marquis – these were all titles that referred to the old, unequal, hierarchical society as it existed before the Revolution," Janssens says.

So what place do these aristocratic titles have in modern-day Belgian society? Can they fit into the egalitarian and progressive society which Belgium aspires to be?

United from the top?

For Janssens, the aristocracy lives on due to the particularities of Belgian society and political developments. "Belgium is a very complicated country with two cultural communities. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries there have been tensions between these two communities. This led to various revisions of the Constitution in an attempt to achieve a political balance."

The practice of ennoblement might therefore be seen as a response to the political situation of a divided country. Janssens explains that it can serve as an instrument to strengthen the cohesion of the country, since it concerns people in both the French-speaking community as well as the Flemish community. They all accept a property title from the King, so they are effectively publicly proclaiming their attachment to the unity of Belgium, since the King is the embodiment of Belgium and the unity of the country."

Janssens admits that the titles have a pre-Revolutionary association but stresses that they have been stripped of their former hierarchy. "All that's left is the word, the symbol, the reminder. For two centuries, the Belgian nobility has been on an equal footing with the rest of Belgian society; it is nothing more than an honorary distinction."

A world unto its own?

About two thirds of the country's nobles live in the Brussels-Capital Region and the periphery, after a mass exodus from Flanders and Wallonia after the radical language laws of the 1930s. Modern-day nobles are increasingly bilingual or sometimes even trilingual – much like the rest of the population.

Belgium has some 35,000 nobles today and their number has risen year on year for two centuries. This is not because the King makes new appointments but rather due to a high birth rate. While Belgium's birth rate is now around 1.5 children per year per couple; for nobles it is around three children.

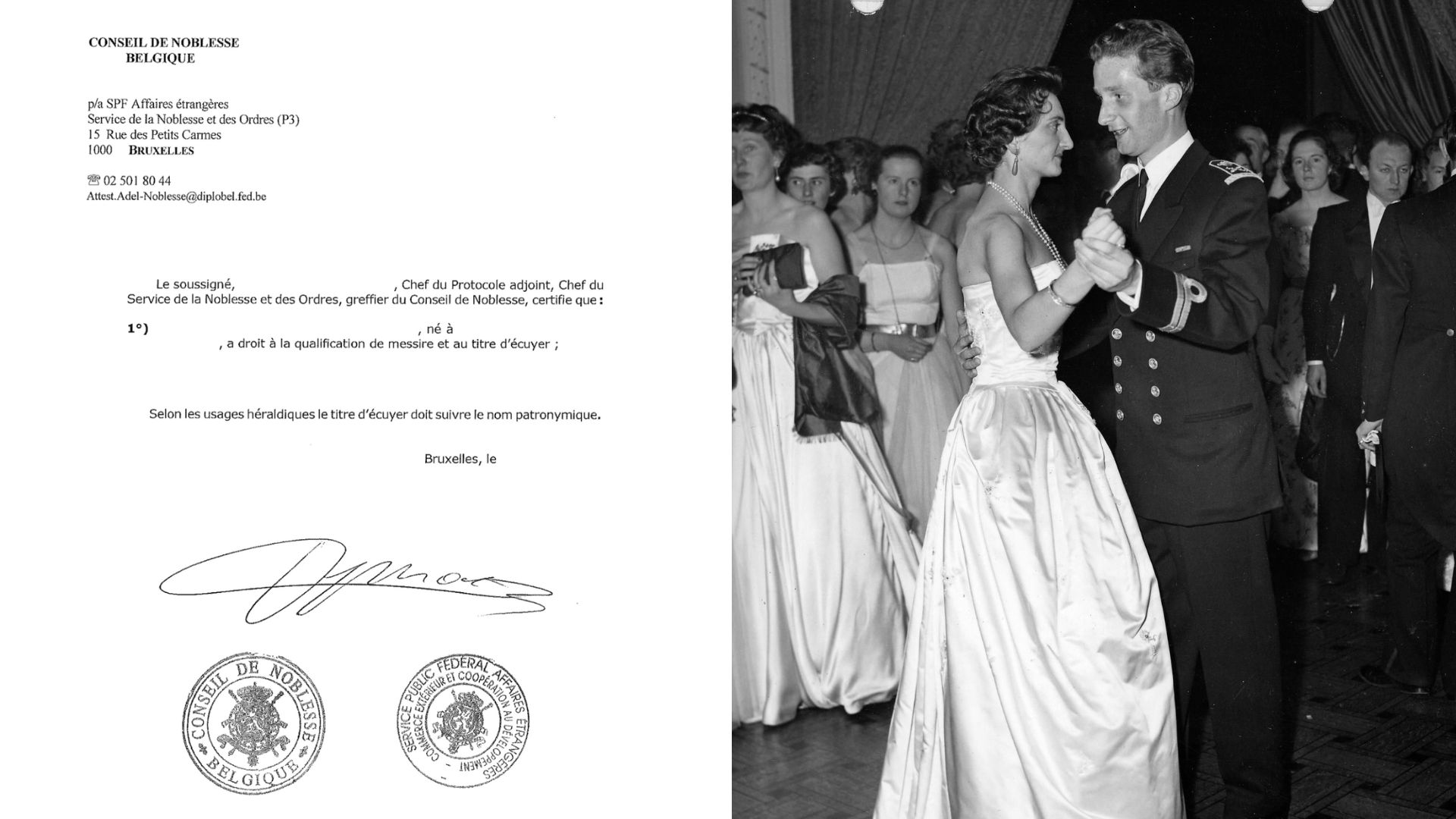

L-R: Certificate of Belgian nobility, issued by the Nobility Council, and Prince Albert dances with Princess Salva de Mérode at the Nobility Ball. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Belga Archives

Contrary to popular belief, the selective soirées known as rallyes are not exclusively for nobles. For the most part, dinners, receptions and conferences organised by nobles welcome "outsiders" as this presents valuable networking opportunities. Janssens says that about half of nobles marry each other whilst the other half does not.

"There are no events that gather thousands of nobles – that doesn't exist. It's an association on paper that may have many members but many never meet."

And although nobility in Belgium does not come with wealth, over half (56%) of the total wealth of Belgium's 500 richest families belongs to nobles, L’Echo reports. "This is partly because many of the new noble titles are bestowed upon wealthy entrepreneurs," Janssens clarified.

But the distribution of wealth in this group has changed dramatically since 1830. The hierarchy of income and wealth within the nobility today is fairly similar to the rest of Belgium. It is, in some ways, a microcosm of Belgian society.

Musicians from group Scala Stijn and Steven Kolacny pose with journalist Annemie Struyf during a ceremony dedicated to people who received a badge of honour in November 2012, at the Royal Castle of Laeken. Credit: Belga / Benoit Doppagne