A recent book explores the massive, often amusing, presence of French in the English vocabulary. It thereby provides one explanation for why Francophones find English so much easier to learn than Dutch. But it is not the main one.

Philosopher Philippe Van Parijs reflects on current debates in Brussels, Belgium and Europe.

“English does not exist. It is French badly pronounced”

La langue anglaise n’existe pas. C’est du français mal prononcé. So says the provocative title of a recent book by the French linguist Bernard Cerquiglini (Gallimard, 2024). No, this is not yet another bitter diatribe against the dominance of English. If the book is in any way polemical it is in so far as it castigates the obsession with linguistic purity to be found among some of the author’s compatriots.

Why panic if French borrows a few hundred or even thousand words from English when English has imported far more from French? According to an estimate quoted in the book, 29% of the English lexicon has French origins, 29% Latin origins, 26% Germanic origins, and 16% comes from other languages.

Asserting on that basis that English is a Romance language or, as the title of Cerquilini’s book suggests, that it is just a dialect of French is somewhat over the top. But that English has been deeply contaminated by French – itself a dialect of Latin misshaped by innumerable cumulative mistakes – is beyond question.

But did this contamination prevent English from thriving? On the contrary, it enabled the old Anglo-Saxon language to give birth to modern English, instead of remaining “a second Dutch”. And it equipped the newly born language with the words it needed to refer to emerging realities. Until at least World War II, Cerquiglini writes, the lexical flow from French to English exceeded the flow from English to French. Since then, it is French that has benefitted most from the cross-Channel traffic. This is how languages help each other. Why complain?

Queen Mathilde of Belgium attends a language learning course at Bruxelles Formation, the francophone government agency for professional training, April 2024. Credit: Belga

After a word had migrated from French to English, its meaning often changed and its pronunciation always did. Hence Cerquiglini’s characterization of English as “badly pronounced French”. The bulk of his book consists in tracing the French origin — sometimes evident but often unsuspected — of contemporary English words.

The import occurred sometimes via the version of French spoken in Normandy at the time of the Norman conquest and by the English aristocracy in the 11th and 12th centuries; sometimes directly from Parisian French when it was Europe’s most prestigious language between the 16th and the 18th century; and above all via the anglo-français that was used mainly for legal and administrative purposes up to the end of the 14th century, after French had ceased to be anyone’s mother tongue in the British Isles.

An entertaining inventory

This leads to an often instructive, surprising and entertaining inventory. For example, English places words of Germanic origin and one of French origin side by side, with closely related but distinct meanings. The culinary examples are familiar: “pig” and “pork”, “sheep” and “mutton”, etc. But there are many more, such as “buy” and “purchase”, “build” and “construct”, “feed” and “nourish”, “end” and “finish”, “forgive” and “pardon”, “seek” and “search”, “meet” and “encounter”, “house” and “mansion”, “holy” and “sacred”, etc.

Many words saw their meaning more deeply altered than others. “Travail”, for example, became “travel”, “journée” became “journey”, “grappe” became “grape”, and both “prune” and “raisin” dried on the way from French to English. The French heritage also frequently combined with Germanic roots to form hybrid words such as “beautiful” and “countless”.

Particularly striking are the cases in which French words generated two distinct English words at different times. Just as “Guillaume” became “William”, “gardien” became “warden” and “garantie” became “warrant” via the Norman variant of French. But the same words were borrowed once again centuries later directly from the Parisian version of French to produce “guardian” and “guarantee”.

There is also the far more frequent ping-pong phenomenon. Many words that English imported from French return to French as anglicisms. “Budget”, “ticket”, “sport”, “tennis”, “penalty”, “scout”, “panel”, “stress”, “cheque”, “pickpocket” and “toast”, are all English words that have a remote French origin but were welcomed back more recently by native speakers of French, often completely unaware of their French pedigree.

Incidentally, I particularly like “pedigree”, which comes from “pied de grue” poorly pronounced: genealogical trees used to be drawn in the form of a crane's foot. I also liked “flirt”, which I thought came from “conter fleurette”, but a footnote in Cerquiglini’s book tells me that this is a bad example, as the English word “flirt” was already used in a related sense in the 16th century, while the earliest occurrence of “conter fleurette” in French dates from the 17th. Too bad.

CERAN in Brussels offers language training lunches to improve people's foreign language skills. Credit: Belga

Common grammar as well as common vocabulary?

Belgians who read Cerquiglini’s book may be tempted to believe that it explains why Francophones find it so much easier to learn English than to learn Dutch. Both English and Dutch borrowed generously from French and Latin, but English far more so than Dutch. There are therefore far more words in English than in Dutch that Francophones do not need to learn because they are simply French words, however weirdly pronounced.

But there may well be another factor that explains even better why Francophones find it easier to speak English than to speak Dutch. It is also a matter of linguistic proximity, yet this time syntactic, not lexical. Many aspects of the syntax are similar in all three Indo-European languages. But some are common to English and Dutch, while not being shared by French, and are therefore equally difficult for a Francophone to learn in both English and Dutch.

For example, the formation of the future tense, which requires an auxiliary in English (“I shall go”) and in Dutch (“ik zal gaan”), but not in French (“j’irai”), or the position of the adjective, which must necessarily precede the noun in English (“a beautiful city”) and in Dutch (“een mooie stad”), but is only sometimes allowed to do so in French (“une belle ville”, but “une ville magnifique”).

There are also some features that are shared by French and Dutch, but not by English, and should therefore make Dutch pro tanto easier for a Francophone to learn. Most obvious is the structure of interrogative and negative sentences, which require an auxiliary in English but not in French and Dutch: “Does he often go to Paris?” versus “Va-t-il souvent à Paris?” and “Gaat hij vaak naar Parijs?”; “He does not often go to Paris” versus “Il ne va pas souvent à Paris” and “Hij gaat niet vaak naar Parijs”.

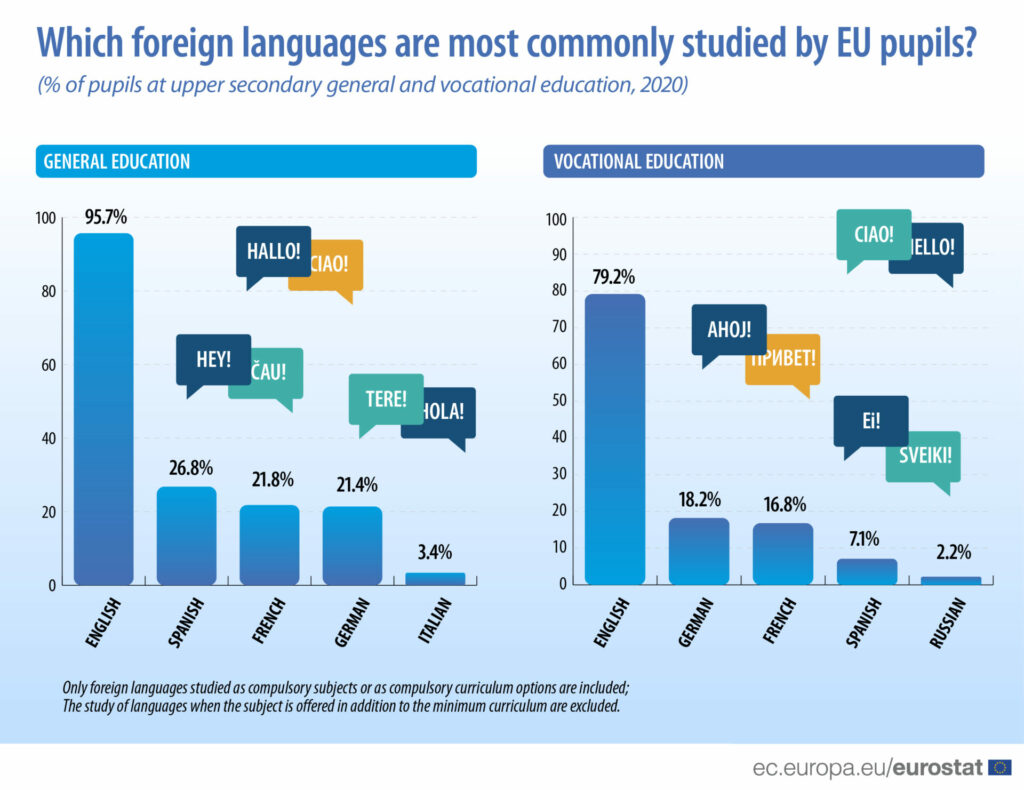

Foreign languages spoken in the EU. Credit: Eurostat

However, there are very salient rules about the position of the verb that Francophones find particularly hard to apply spontaneously when speaking Dutch, while having no analogous difficulty when speaking English because the rules that govern the position of the verb are essentially the same in French and in English. Firstly, when a main clause starts with a complement, the verb must precede the subject in Dutch (as it must in all other Germanic languages), whereas in English, as in French, the respective positions of the subject and the verb are not affected by the position of the complement: “Elke week ga ik naar Parijs” versus “Chaque semaine, je vais à Paris” and “Every week, I go to Paris”.

Secondly, in a subordinate clause, the verb is generally required to follow the complement in Dutch (as well as in German and in Frisian, but not in Scandinavia’s Germanic languages), whereas in English, as in French, the word order is the same in a subordinate clause as it is in a main clause: “Ik geloof dat hij elke week naar Parijs gaat” versus “Je crois qu’il va à Paris chaque semaine” or “I believe that he goes to Paris every week”. These two differences matter greatly. When speaking Dutch, Francophones tend to struggle far more with positioning their verbs than with finding their words and pronouncing them.

When crossing the channel in the 5th century AD, the Anglo-Saxons presumably positioned their verbs in roughly the same way as does today’s Frisian — the living language generally regarded as closest to that of the Germanic invaders. From the evidence available, it seems that these rules persisted in Old English, the version of English that preceded the Norman Conquest. Their subsequent replacement can therefore plausibly be conjectured to reflect another influence of French. I was surprised not to see this question discussed in Cerquilini’s book. Showing that French shaped not only the lexicon of today’s English but also its syntax would strengthen the claim that English is just French badly pronounced.

Bernard Cerquiglini's book. Credit: Gallimard

Why French and Dutch native speakers find English easier to learn

Establishing the lexical and syntactic proximity between French and English helps us understand why French native speakers learn English more easily than Dutch. But if French and English are so close to one another, why is it that native Dutch speakers learn English so much more easily than French? Leuven University researchers have shown that pupils in Flemish schools knew on average more English words than French words at the beginning of the first year of secondary school, after they had had at least three years of French and before starting to have English lessons.

One explanation is that while only 27% of the English words may be of Germanic origin, most of the most common words are among them. For instance, if you are used to “Hij werkt en zingt in het huis”, it is easier to learn “He works and sings in the house” than “Il travaille et chante dans la maison”. In support of this, the million-word Brown University corpus of written American English did not identify a single word of Romance origin among the 100 most frequently used words.

Thus, English is lexically and syntactically closer to both French and Dutch than they are to one another. It is located, linguistically speaking, between them and combines features from both. This greater linguistic proximity is no doubt one reason why both French- and Dutch-speaking Belgians find it easier to learn English than the other national language. But it is not the main one.

Exposure and attitude are even more important. Whether in-person or online, whether for business or for fun, most Belgians have more daily contact with English than with the other national language. Partly for this reason, they also have a more positive image of it. As a result, while national bilingualism tends to decline, competence in English keeps growing. And more and more young Belgians who do not have the same native language communicate with one another in that badly contaminated Germanic language, in that terribly pronounced dialect of French. Distressing?