“You know, I have 16,000 negatives of Belgium between 1970 and 1985. I wanted to share all these incredible images of the evolution of a country - it would have been silly to keep them in an attic.”

Brussels-born photographer Alexandre Laurent inherited from his father thousands of negatives and a passion for taking birds-eye photos of Belgium from a plane. He was born in Berchem Sainte-Agathe in 1964 to French parents. His father, also a photographer, moved to Brussels in 1958 to do a photography internship with the Associated Press.

With 1958 being the year of the World Expo in Brussels, the city had just undergone a vast architectural face-lift, with the constructions of tunnels, new main roads and demolishing the old.

“My father set up his own business and came up with the ingenious idea of proposing to the media of the time, mainly the newspaper Le Soir, the idea of a press photo seen from the sky,” Alexandre told The Brussels Times. “He photographed all the major works (roads, ports, civil engineering and others) of the 70s and 80s that I have carefully kept.”

Belgian-French photographer Alexandre Laurent in action.

Alexandre’s father would bring him on these flights as his assistant, where he could also earn some pocket money. “As a kid I followed him everywhere during my weekends and holidays and he passed on to me his passion for photography and aviation,” he continued.

Exhilarated from his childhood experiences, Alexandre left school at 17 and started as an apprentice with his father, before setting up his own photography and graphic design business. In 2007, he got back in touch with his father's pilot, Pierre Schoemans, to organise another flight. His idea was to publish a book showing “the evolution of a city, my beloved Brussels.”

And his beloved city has indeed changed. His intergenerational project acts as a testament to these changes, most notably the scar of “Brusselization” still marking the city’s skin today.

Demolition of Brussels' covered market on 26 April 1963. Credit: Belga Archives

Brusselization is a pejorative term in architecture, defined as a "haphazard urban development and redevelopment," associated with “careless introduction of modern high-rise buildings into gentrified neighbourhoods.”

A phenomenon that has its roots in the ambitious urban project which began in the Belgian capital during the 1960s. It speaks of a time when the laissez-faire attitude of town planners allowed the sprouting of ugly high-rise buildings in juxtaposition with the city’s quaint 19th century charm.

In its aftermath, the Belgian capital was left with mismatching buildings, built with indifference to its surroundings which underpin a lack of vision for the city as a whole. It is associated with the demolishing of historic buildings and architectural gems. Famous cases include Victor Horta’s Maison du Peuple, which caused an international outcry when it was demolished in 1965. Today, the Sablon tower sits in its wake as an eyesore looming over Rue Haute.

Maison du Peuple-Volkhuis, demolished in 1967. Credit: Horta Museum

This is just one example of the changing face of the city. Wanting to follow in his father’s footsteps, Alexandre documented how the city changed through the art of aerial photography. Two sets of photos of similar locations, one taken by his father in 1970 and another by him in 2010, serve as a testimonial to the monumental urban changes the city has witnessed.

After three years of “various adventures” with Belgian aviation authorities and Zaventem Airport, Laurent self-published his book 40 Years in the Skies over Brussels. He kindly sent us some of his favourite shots, dated both from 1970 and 2010, and we studied some of the key differences.

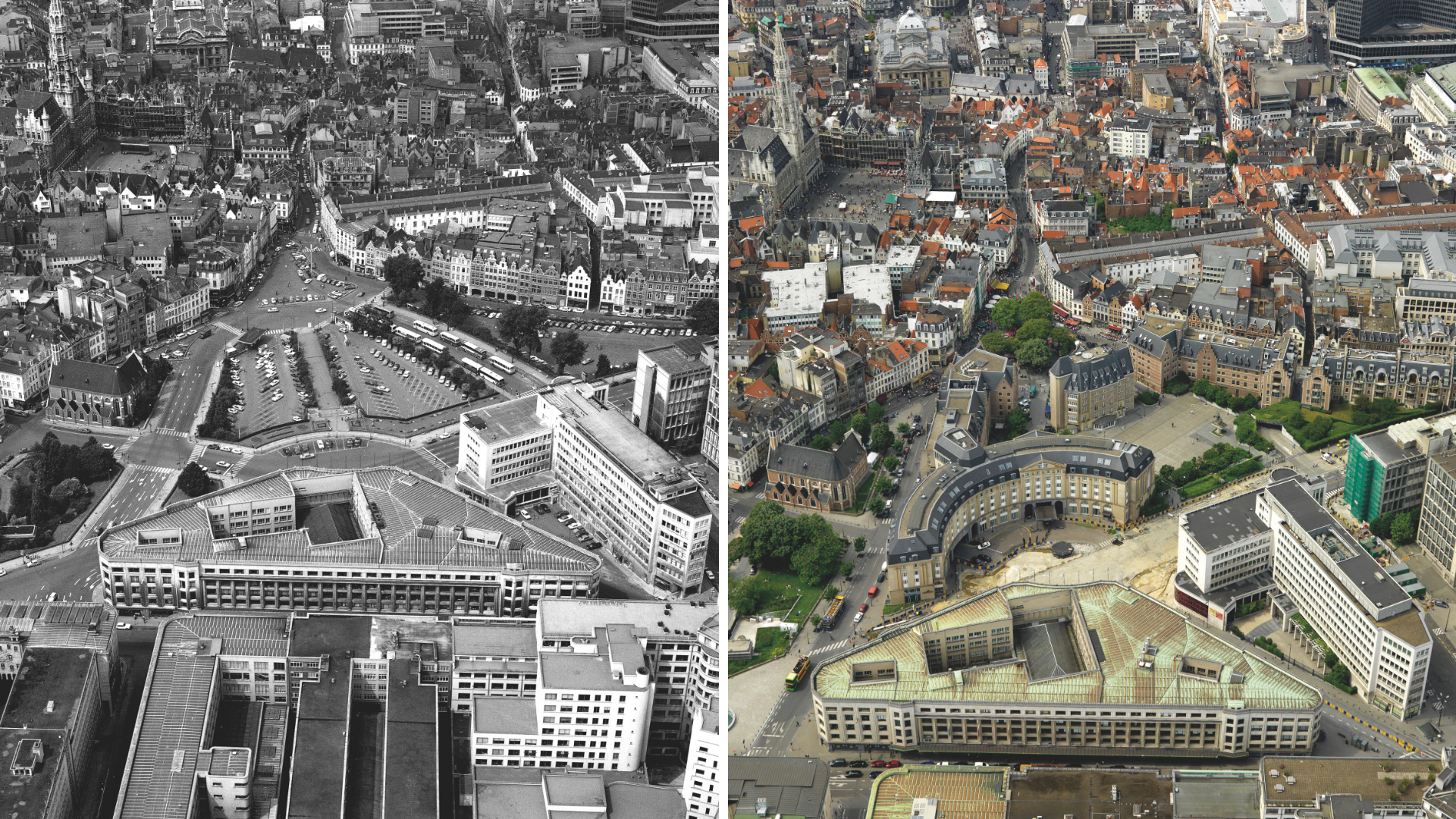

In the city centre

The first, glaring, thing we noticed in the 1970 series: a coach parked in the middle of the Grand Place. It is parked alone, but sharing the square with some scattered market stalls. The differing lives of the Grand Place can be seen in just one photo: a marketplace and then a car park.

Brussels-Central station area in 1970 (left) and 2010 (right). Courtesy of Alexandre Laurent

Just a few years later in 1972, Brussels banned cars in the square, to the fury of local business owners. It opened the way for the square to become the popular tourist attraction of today – which we can already see in the 2010 photo.

In both photo series, we see Horta’s famous Brussels-Central station in the foreground. A visible difference in 1970, is that the station was surrounded by a large car park and petrol station. Belgium’s defunct national airline, Sabena, had its headquarters based next door to the left. The empty car park was eventually removed to make the journey from the central station to the Grand Place more pleasant for visitors.

A closer look at how the view around the station looked in 1975. Here, drivers are demonstrating and blocking the roads so that few people could reach the Central Station of Brussels and Sabena headquarters. Credit: Belga Archives

Today and in 2010, many buildings surround the entrance on what is known today is the Carrefour de l’Europe (which houses an actual Carrefour supermarket). They were built in the 1980s, today they house commercial businesses such as Hilton hotel, a Carrefour supermarket and a Brewdog pub.

The statue of Don Quixote/Sancho Panza and the Place d’Espagne also did not exist in 1970. One theory suggests the statue was put there in the 1990s to recognise Brussels as the place where Miguel de Cervantes' literary classic was first published outside the Iberian peninsula in the 1600s.

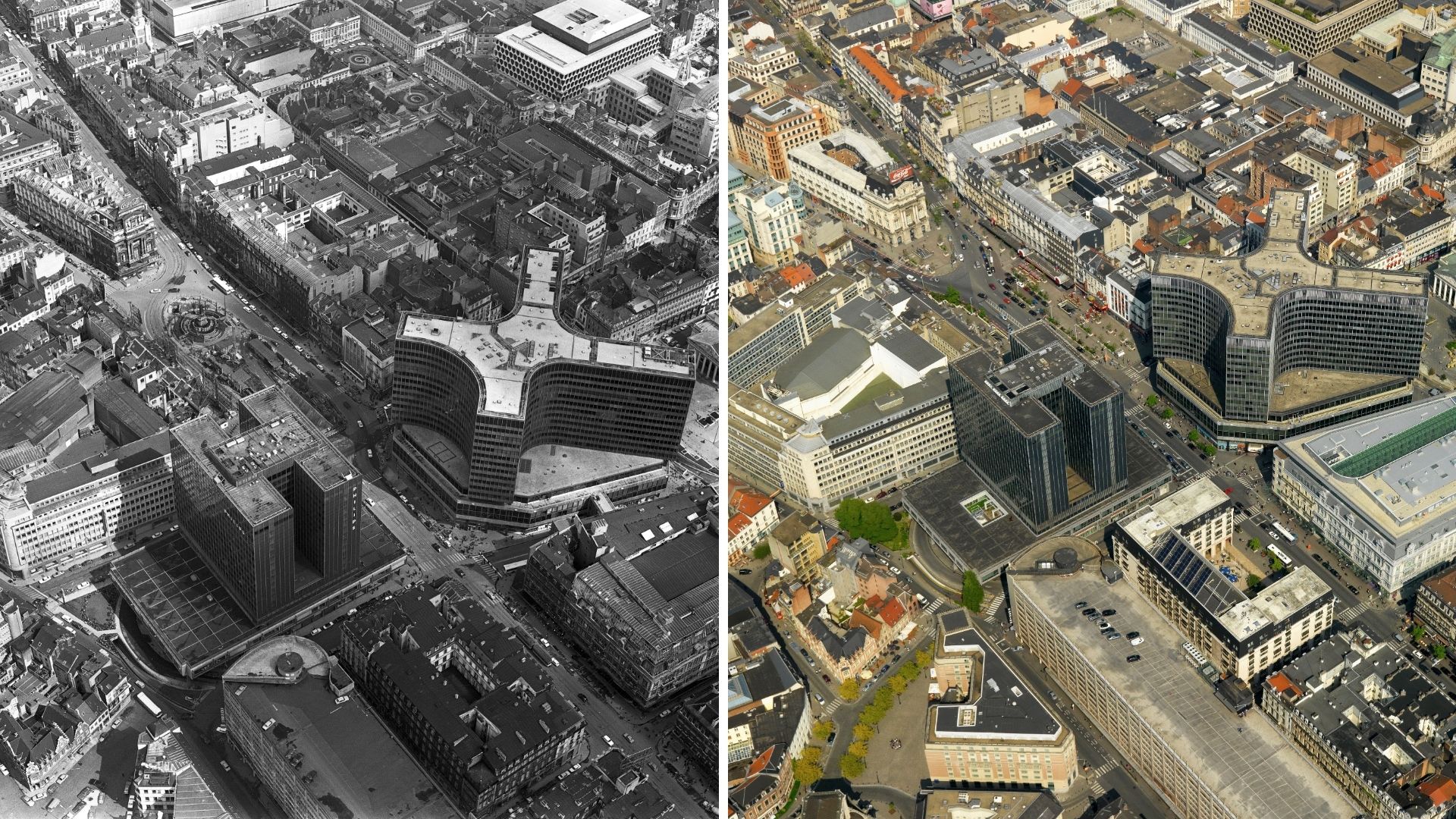

Area in Brussels around Place de Brouckere in 1970 (left) and 2010 (right). Courtesy of Alexandre Laurent

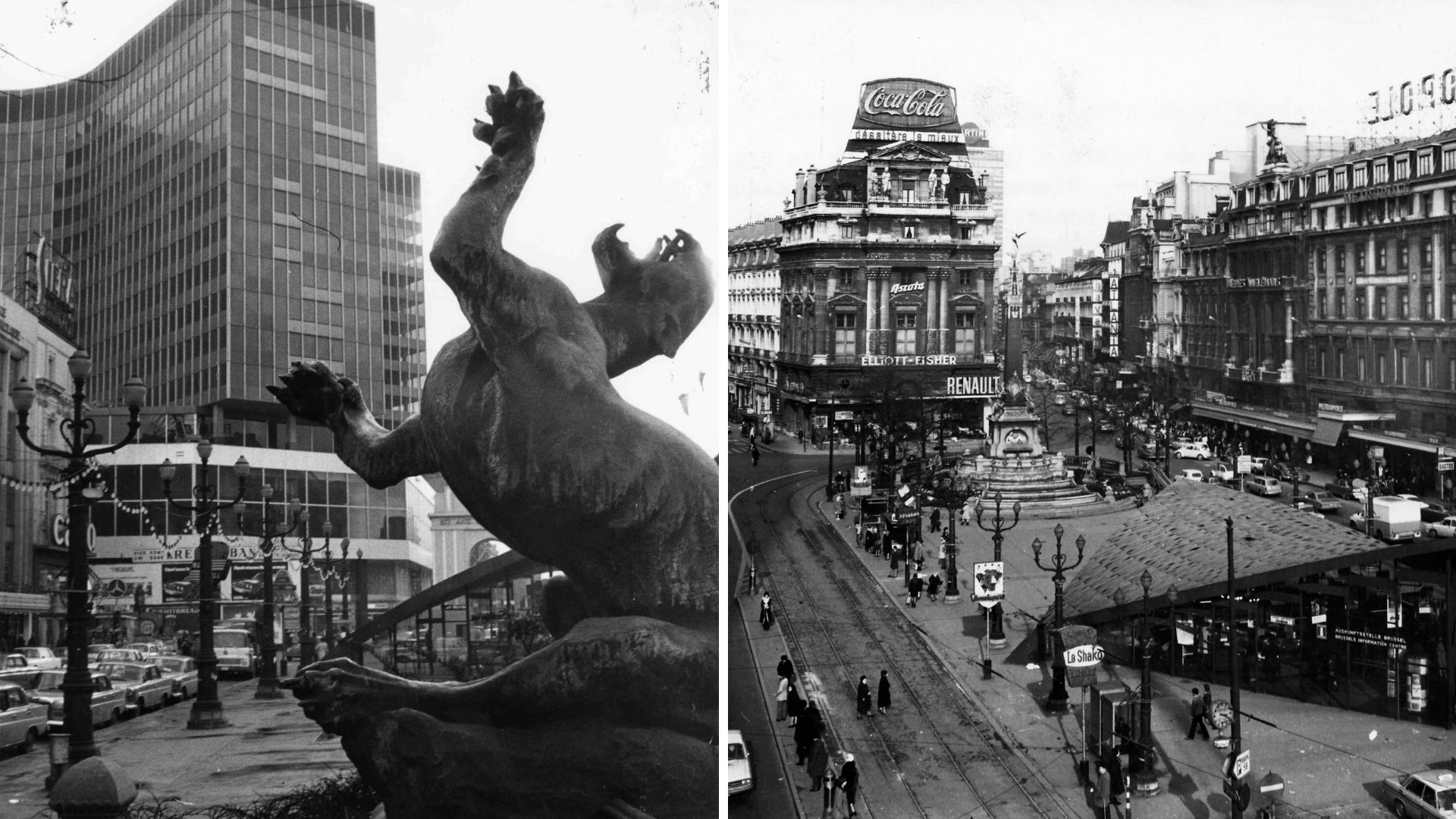

Further up the road towards we find the iconic Place de Brouckere. The timeless Coca-Cola advertising sign is visible in both decades. In 1970, the square resembled its interwar glory years: more neon advertising signs and a now-vanished tramline cutting in front of a now-disappeared fountain.

The fountain, in tribute of former Brussels mayor Jules Anspach, was dismantled due to Metro works (and also to allow traffic to flow better). It was partly rebuilt in a reduced form in the Marché aux Poissons in Saint-Catherine in 1982. Either way, both photos will look unrecognisable to recently arrived Brussels residents who today enjoy the pedestrianisation of Bourse and the Boulevard Anspach (and its many e-scooters).

On the left, the Anspach fountain, which today can be found in Sainte-Catherine. On the right, the square in 1970. Credit: Belga Archives

European Quarter

Another seismic event in these 40 years was the growth of the European Union institutions in the city. In Alexandre’s photos, we see first-hand how the development of the EU completely changed what was once known as the Leopold Quarter. Today, it is known as the European Quarter. The arrival of the monolith construction of the European Parliament in 1990s, brought about considerable cosmetic change to the area, visible in the 2010 photo.

The European Quarter (formerly known as Leopold Quarter) area in 1970 (left) and 2010 (right). Courtesy of Alexandre Laurent

In 1970, Place Luxembourg was known for its Leopold Quarter train station (later renamed to Brussels-Luxembourg), which still sits below the Parliament. The only existing building from this period is the small Station Europe which sits between the square and the EU institution, which used to be part of the old train station. Plux, as it's colloquially referred to today, still appears to have its famous bars but its large terraces were taken up in 1970 by… parking spaces.

Picture dated 1 May 1991 is a sight of the Leopold Quarter railway station of Brussels. The station was later renamed Brussels-Luxembourg railway station. Work on the new EP building was about to commence. Credit: Belga Archives

From the angle 0f the photograph, Alexandre allows us to see how the Parliament’s esplanade follows the same curved route of the train line. The Parliament’s thousands of conference rooms and offices are all built over the 8 open air platforms of the former Brussels-Luxembourg station. It was, like the Senne river, pushed underground. In 2010, many of the neighbourhood’s old houses (seen in the 1970 photo) have been replaced by modern blocks of flats – assuming to house the growing population of EU migrants working in the institutions.

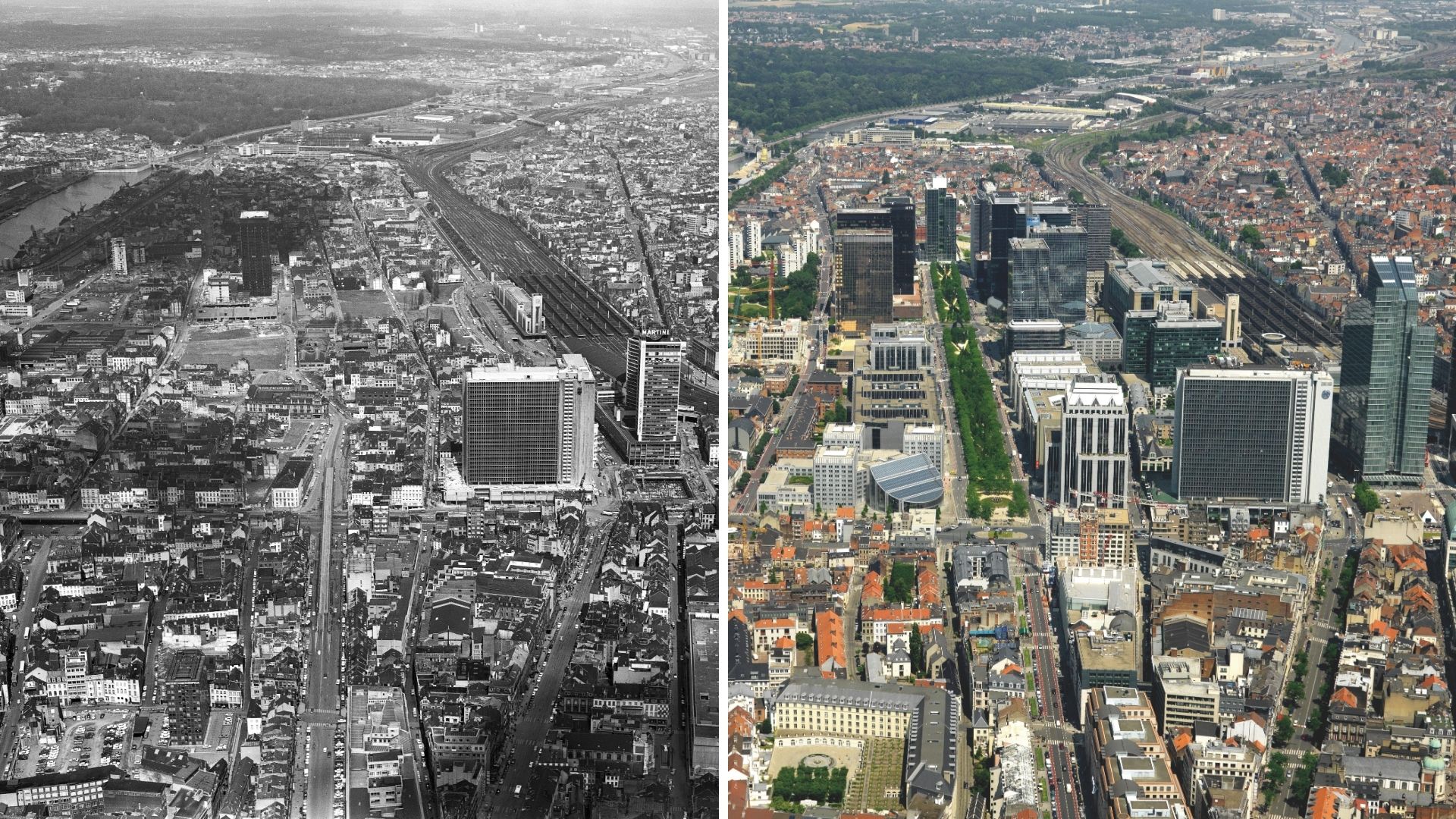

Brusselization in the north

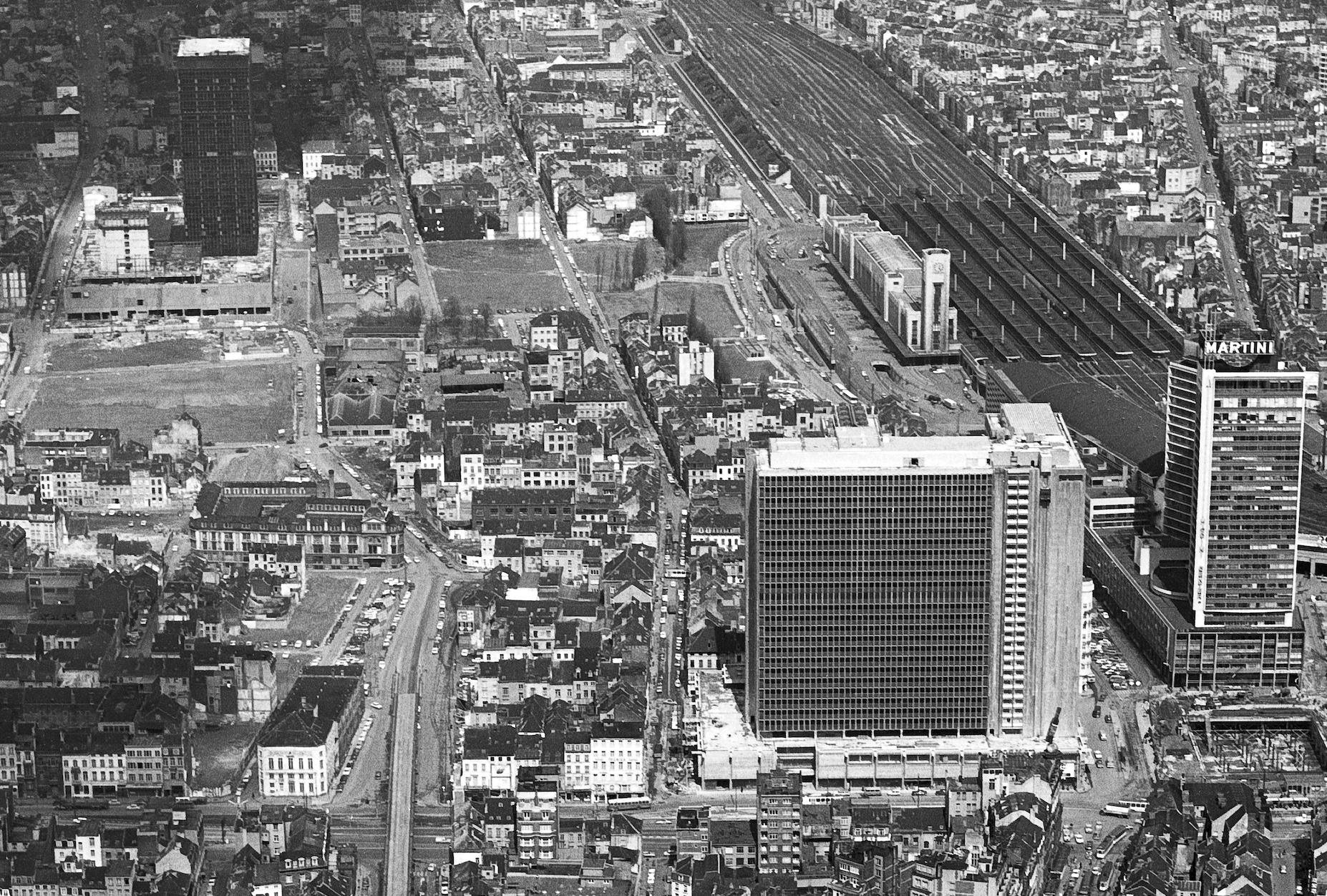

As our eyes travel to the north of the city, we enter into the stronghold of Brusselization. The vapid and vacant business district around Brussels-North station is this era’s piece de resistance. Back in the 1960s, the order of the day was to “modernise” the Belgian capital to make it into New York’s European rival. This was done by throwing up large Manhattan-style office buildings to usher in a new area of capital, with skyscrapers shooting up like financial stocks across the historic city.

The Northern Quarter area in 1970 (left) and 2010 (right). Courtesy of Alexandre Laurent

The first building that catches our eyes in the 1970 photo is the emblematic Martini Tower on the Place Rogier, also known as the Rogier Centre. It was decorated with a giant Martini advertisement logo, which earned it its name. The 1958 tower was a much-loved symbol of the city, housing restaurants, exhibition spaces, two theatres, luxury flats and a fancy terrace bar. Conversely, this was a key part of the urban renewal plan called the Manhattan Plan – the doctrine which laid the foundations for the Brusselization rebrand of the Northern Quarter which began in the 1960s.

However, the scheme was half completed and broke down due to corruption. The tower was demolished in 2001, and replaced by the new Rogier tower, visible in the 2010 photo. An important feature of the Place Rogier photo (1970) is the ongoing construction of the Brussels Metro, visible by the below-surface level construction work happening under the tower. Brussels was in the middle of building its public underground system which would help dislodge the car’s dominance in the city.

The Martini tower at the Brussels Rogier square. The tower was constructed in 1961 and demolished in 2002. Credit: Belga Archives

When looking past the Martini tower, we notice a distinct lack of glass-windowed skyscrapers which now encircle the Northern Quarter. Strikingly, Brussels-North station stands alone, isolated. The area around it appears to have been razed in order to prepare for the Manhattan plans's towers and office, which by 2010 photo have been built and are still there today.

Alexandre’s photos document the flattening of the area, much maligned to this day, where poorer houses dating from the 19th century were demolished to make way for flats, displacing many Brussels residents. The vast empty fields which sit on the left of the station will, within a few decades, be taken over futurist office spaces, many of which lie empty today as a testament to the project’s failure.

Zoom in on the isolated old Brussels-North station in 1970. Courtesy of Alexandre Laurent

With his project, Alexandre also offers an embittered take of the changes from the perspective of a Bruxellois. “In my project, you can see the scars left by the megalomania of politicians and architects of the time, as well as the repairs and adaptations that were made afterwards. They are still being made today to try and make people forget about this madness!” he said.

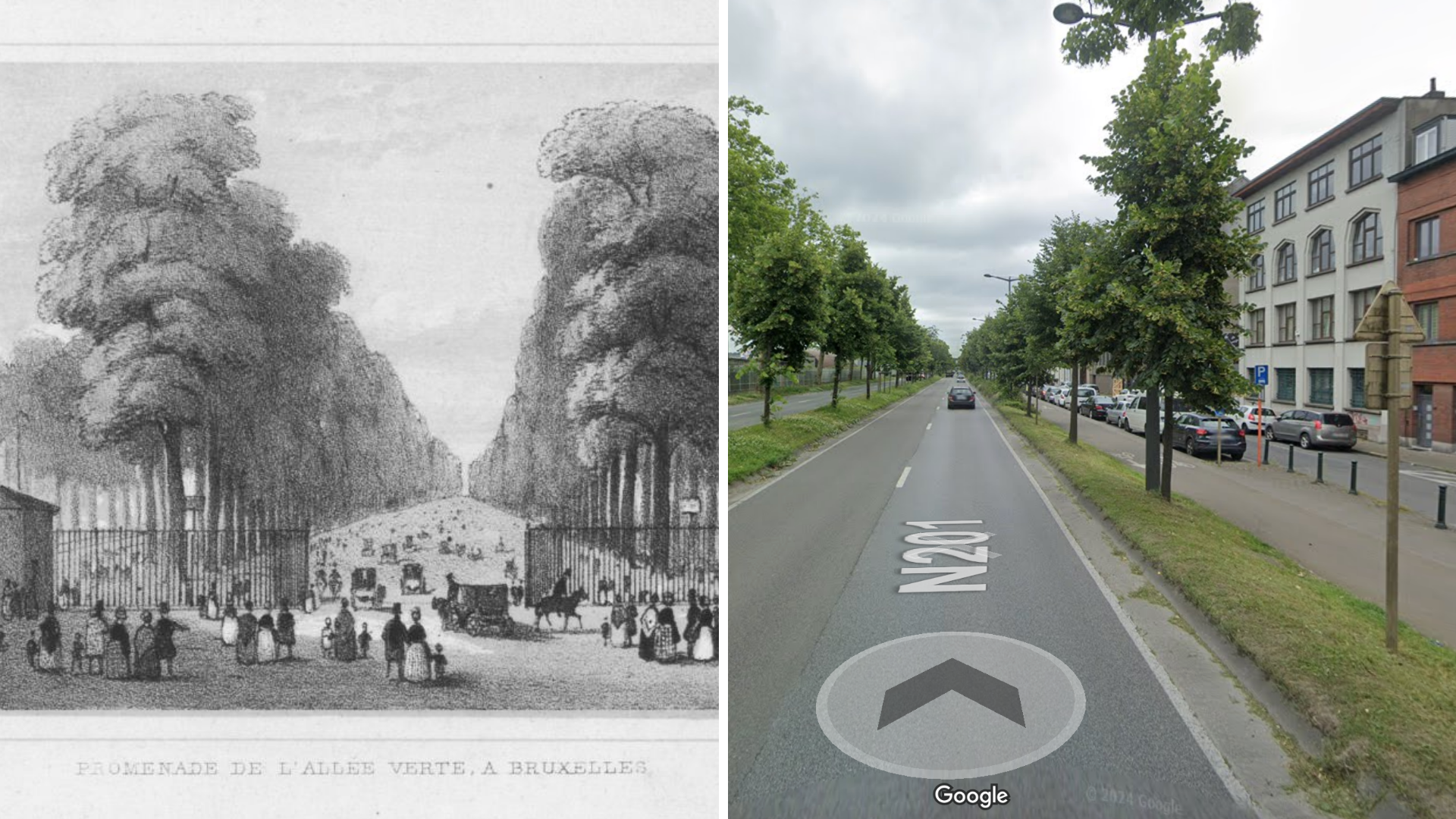

Nowhere is this "madness" more apparent that the the Avenue de l’Allée Verte, which can be seen where train tracks run along the canal (on the far-left). This avenue underwent vast changes, going from upper class hang out to where Brussels’s first ever train station.

Allée Verte station, entrance pavilion on Boulevard Baudouin, around 1950, AVB/FI C-2416. Credit: Brussels Heritage

The train tracks, which follow the canal, are still visible in the 1970 photo. Today, the old route is an unremarkable industrial road with warehouses – a far cry from the Allée Verte’s glory days. Up until the 19th century, it was a very prestigious riverside park (with the same name) following this same route.

The promenade was populated by the wealthier classes of Brussels going for their weekend walks. It often made an appearance in travel accounts of Brussels up until the 19th century. It was demolished in the 1830s to make way for Brussels’ first ever train station due to the advent of the industrial revolution given its position next to the canal, making it ideal for transport. It would fall out of use with the construction of the North-South railway line in 1952.

Allée Verte in the 19th century and today on Google Maps

These dramatic changes symbolise the many changing faces of Brussels – from its green foundations to an industrial hub. In the 1970 photos, the docks next to the train tracks are still operating thanks to the presence of cranes for loading and unloading. Today, these areas are home to a gravel and sandpit deposit and a recycling centre, thereby still maintaining an industrial edge.

‘Feeling of freedom’

It would be easy to continue picking out differences, and there are surely many glaring ones that have been missed. However, the story one can gage from Alexandre’s project is a photography documentation the controversial urban history of Brussels over 4 decades.

In terms of material changes, the most notable are building density which was much greater in 2010 (and today). The 1970s offered more space – albeit temporarily. The city has grown, and Alexandre’s photos are a testament to this. But another overarching story of 1970s Brussels is the omnipresence of the car. From car parks to boulevards with many traffic lanes, much of the Belgian capital was redesigned in this era to facilitate car travel.

“There's more and more greenery today, as the main squares have been emptied of vehicles. Everything is underground now,” Laurent says. “But yes, real estate is one of the most visible things from the air, depending on the era and urban planning regulations.”

Area around the Anderlecht, south Brussels in 1970 (left) and 2010 (right). Courtesy of Alexandre Laurent

“Main roads have also been redeveloped i.e. - the ring road, the inner ring road, the main boulevards,” he continued. Transport of industrial goods used to be brought to the centre of the city before in transport hubs like Tour and Taxis, Schaerbeek and Etterbeek. He says this is because companies are also now located on the outskirts of the city, rather than inside.

Despite his anger around some of the changes the city has seen, Alexandre is still a proud Bruxellois and Belgian. He carried out this project as a "gift and thank you" to the country that he feels gave a “French family who arrived in 1958 the opportunity to develop both personally and professionally.”

But Belgium has indeed changed, he agrees. “For some it is for the better, for others, for the worse. Personally, the country has changed like our world has – and it is finding it hard to keep up with the pace. It’s good to live here in spite of everything.”

With these photos, he wanted to bring people together to encourage debate between the generations. He says he had the “opportunity to talk to some older people who told me about their neighbourhoods and towns, with some incredible anecdotes - it's very enriching.”

When asked why he prefers renting an aeroplane rather than a helicopter, he says: “The feeling of freedom, of being able to stare at the landscape while moving, of being able to place the plane and photograph your subject is exhilarating,” Alexandre exclaims. “The acrobatics performed by pilot Pierre Schoemans to keep the plane in position despite the wind and capricious weather are incredible.”

Belgian-French photographer Alexandre Laurent in action.

Having used the same pilot as his father did, for Alexandre, this also goes beyond a practical arrangement for his project. “The common thread running through the project was the father, the son and the same pilot - a story of family and friendship.”

Alexandre does not currently have other plans to fly again for a new series which could document the many changes the city has seen since 2010.

“The problem is money and an interested media or sponsor, for 2010 I financed it alone on my own account, which is impossible currently. I'm now 60, after that it will be something for my children and grandchildren.”