This weekend families are flocking to the cinemas to see Paddington in Peru, the third instalment of the beloved film franchise about the adventures of an adorable bear.

Paddington has instantly recognisable qualities: a floppy red hat, impeccable manners, a worrying marmalade habit, a leather suitcase and, of course, a blue duffle coat.

That last element of the Paddington picture is worth pausing for. Where does the sturdy, unassuming material, prized for ursine outerwear, hail from?

The answer is the small Belgian town with a big legacy: Duffel.

Nestled midway between Brussels and Antwerp the town of just over 17,000 people has an outsized claim to fame as the place that quietly shaped our wardrobe. It did this not through imperial conquest or grand innovation, but through a humble, nubby, thick-woven woollen fabric.

Sint-Martinuskerk in Duffel, Sunday 10 May 2020. Credit: Belga

Duffel is first mentioned in chronicles in 1059 as Duffla, which is thought to be derived from the Celtic word dubro or water, a reference to the Nete river flowing next to it. Its name changed to Duffle, but then Duffele after 1350, and from 1684, all documents bear the current name.

Duffel’s eponymous fabric first emerged in the 15th century, produced locally and cherished for its sturdiness. This heavy, coarse wool, a broadcloth known as Flemish laken, was perfect for the needs of the era: from monks in need of durable robes to soldiers seeking protection against the damp.

Flemish weavers who migrated to England in the 1500s brought the manufacturing process with them and Duffel eventually lost its position as the preeminent producer of the material – although the anglicised version of the name stuck.

The 11th to 13th centuries were a golden age for the medieval Flemish cloth industry. But then it began to decline seriously.

Army gear

By the time the 20th century rolled around, the material had transcended its regional roots, making its way into military gear. British and American naval forces adopted the fabric for their duffle coats, shielding sailors from the biting cold.

The British Royal Navy’s duffles were made from 1896 and are thought to have been first worn by marines on an expedition to Antarctica. They were oversized because sailors shared a communal duffle coat, whenever they had to go up on deck: the generous dimensions were needed to accommodate all shapes and sizes.

The hood is usually called a ‘pancake hood’ because it’s designed to lie flat against the back of the coat, like a pancake. But why are they so big? Because they were originally designed to fit over officers’ peaked naval caps. In the 1950s, these coats were fitted with toggle-and-rope fastenings in polished buffalo horn, which have since become a signature.

British Royal Navy in Duffle coats watching for enemy planes on board the destroyer HMS Atherstone off Plymouth, 7 March 1942.

Around a century ago, an equally practical (and shapeless) cousin emerged: the duffle bag. With its drawstring top and cavernous interior, it became the luggage of choice for everyone from seafarers to gym-goers.

Perhaps the most famous human to wear a duffle coat also has a Belgian connection: Field Marshal Bernard Law ‘Monty’ Montgomery. The man credited with liberating Brussels during the Second World War, and who has a roundabout named after him, popularised it during his campaign in Tunisia.

Gifted coat

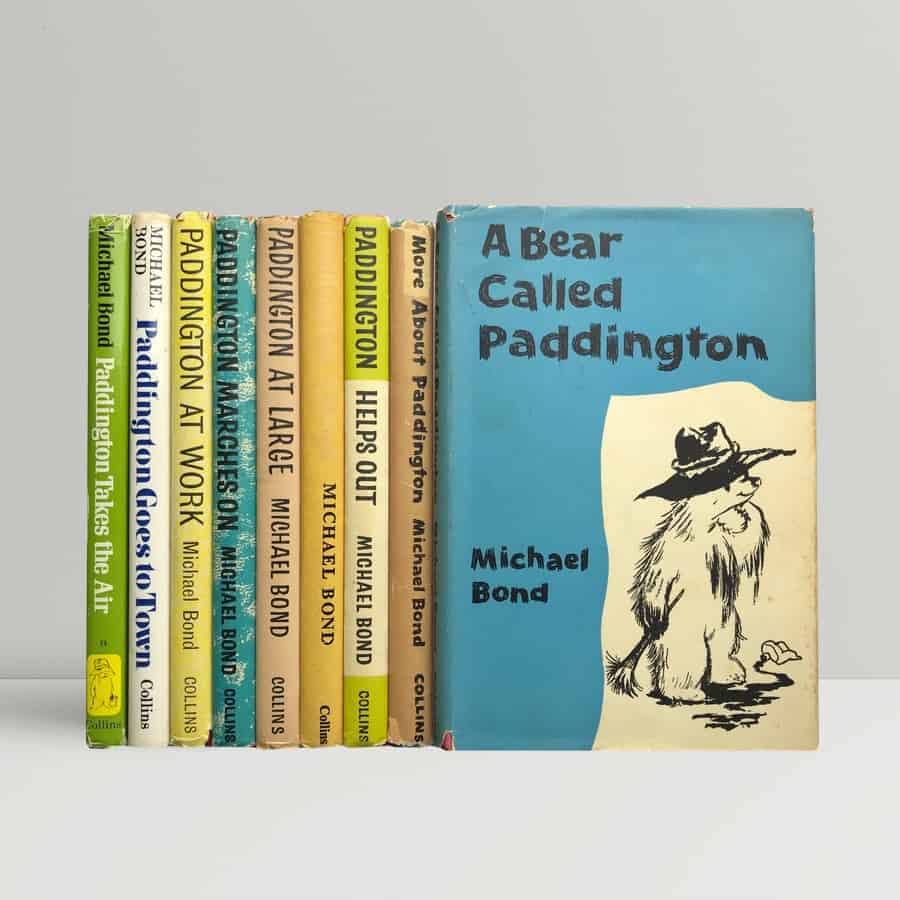

As for Paddington, he did not arrive from deepest, darkest Peru wearing his duffle coat. He only came with a hat, from Uncle Pastuzo, and a luggage label tied around his neck. The duffle coat was a present from the Brown family not long after they took him home. But the Peruvian-born, London-adopted icon of wholesome mischief is never seen without his trusty blue duffle coat.

An early copy of Paddington written by author Michael Bond, without his Duffel coat

Where would he be without the coat that’s endured endless calamities, from the Amazon jungle to Paddington Station? A lesser pelt would have given up long ago, succumbing to marmalade stickiness and repeated mishaps. But not the duffle coat. Much like its namesake town, it is built for resilience, ready to withstand the wear and tear of generations.

Duffel today

So, what has become of Duffel in the 21st century? It’s still here, a charmingly quiet town, boasting a few medieval landmarks, some scenic waterways, and an enduring sense of self-sufficiency.

The main church, St Martin’s, first built in 1150 was destroyed in the First World War – its high tower was an easy target for the advancing German enemy troops – and rebuilt identically in the 1920s.

It has the ruins of the Kasteel Ter Elst, monastery of the Convent of Bethlehem, the 1923 Cinema Plaza, Duffel Fortress, part of the outer defence belt around Antwerp, double Michelin-starred restaurant Nuance, and Antwerp University’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, which boasts possibly the largest collection of pickled human brains.

Illustration picture shows in Duffel, Sunday 04 August 2019. Credit: Belga / Hatim Kaghat

Tourists looking for a deep dive into its textile history might be a little disappointed: there’s no grand duffle museum, no international woollen fabric festival. There is, however, an odd grey stone statue of a headless body in a duffle coat on a roundabout on Hondiuslaan and Spoorweglaan.

If there were any true fairness in the world, a scene might be inserted in which Paddington – always meticulous in his gratitude – pauses to acknowledge the town that indirectly made his adventures possible.

Will it happen? Probably not. But that doesn’t mean we can’t take a moment to appreciate the town that clothed the world – and a certain bear.

Paddington in Peru. Credit: Sony Picture Entertainment