It's easy to dismiss Huy as just another small Belgian town with red-brick houses, a riverside citadel, and the rhythm of local politics quietly ticking away. But in the shadow of the Meuse, a local politician has edged too close for comfort to one of the world's most powerful regimes.

Eric Dosogne doesn't fit the mould of a geopolitical actor. A local Socialist Party (PS) stalwart, he served as councillor and, later, as a replacement councillor when Christophe Collignon left for regional office. For many, he's been the image of grassroots governance: diligent, affable and devoted to Huy, a small town in the province of Liège.

However, according to the China Targets investigation, conducted by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) with Le Soir, De Tijd and Knack, the Belgian intelligence service (VSSE) has twice warned Dosogne about his ties to Chinese officials. There are now concerns he may have crossed the line between diplomacy and collaboration.

At the heart of the matter lies a conversation. Dosogne is said to have agreed to update a Chinese contact on the activities of Samuel Cogolati, the co-leader of Ecolo and one of Belgium's most vocal critics of China's treatment of the Uyghurs. The revelation prompted the first quiet intervention from the VSSE. When that went unheeded, a second warning followed. According to insiders, PS leader Paul Magnette and Cogolati himself were both discreetly informed.

Le Soir repeatedly contacted Dosogne over several months, but he has remained largely silent. Last October, he insisted via text that he had "never had compromising relations with China." Beyond that, nothing.

The Chinese and Belgian flags side by side. Credit: Belga

For those familiar with Huy's unusual relationship with China, the warnings perhaps come less as a shock than a confirmation. Since 2002, the town has been twinned with Taizhou in eastern China – a tie that Dosogne nurtured with remarkable enthusiasm. He visited Beijing, Shanghai and Nanning, welcomed delegations, and frequently appeared at Chinese cultural events. In 2017, he attended a forum on "human rights and museology" in Nanjing – all expenses paid by the Chinese government.

"I think China has made progress on human rights," he told the regional press at the time, unironically.

What strikes many observers isn't just the closeness of these links, but the openness with which they were pursued. When a Chinese delegation came to present its version of the Tibetan question in Huy's town hall, it was Dosogne who introduced the event. When the ambassador visited, Dosogne stood by his side. He even credited himself with restoring what he called a "great friendship" between the city and Beijing.

Yet the friendship wasn't always so warm. In 2012, when Huy welcomed the Dalai Lama for the fifth time and awarded him honorary citizenship, Chinese officials were furious. They demanded a meeting with city leaders and urged them to cancel the visit.

Joseph Georges, then deputy mayor, recalls the conversation vividly: "They reminded us that China is a great power with good relations with Belgium. But we told them, politely, that the visit would go ahead," according to Le Soir.

The larger game

In hindsight, Huy may have been the perfect stage for a soft power experiment. Quiet, out of the limelight, and home to Yeunten Ling – one of Europe's largest Tibetan Buddhist centres – it offered both strategic and symbolic value to Beijing. While national governments grew warier of Chinese influence, local councils often remained openly flattered by attention and the promise of "partnership."

This strategy has played out elsewhere. In 2023, the Financial Times, Der Spiegel and Le Monde revealed that Frank Creyelman, a former MP for the far-right Vlaams Belang, had been informing Chinese officials for over three years. But Dosogne's case suggests the Chinese approach is not confined to one side of the political spectrum.

When Le Soir asked about its relationship with the former acting mayor, the Chinese embassy did not deny it. Instead, it issued a carefully worded statement: "The Embassy of China in Belgium is committed to building bridges, opening windows and paving the way for exchanges between the Chinese and Belgian people."

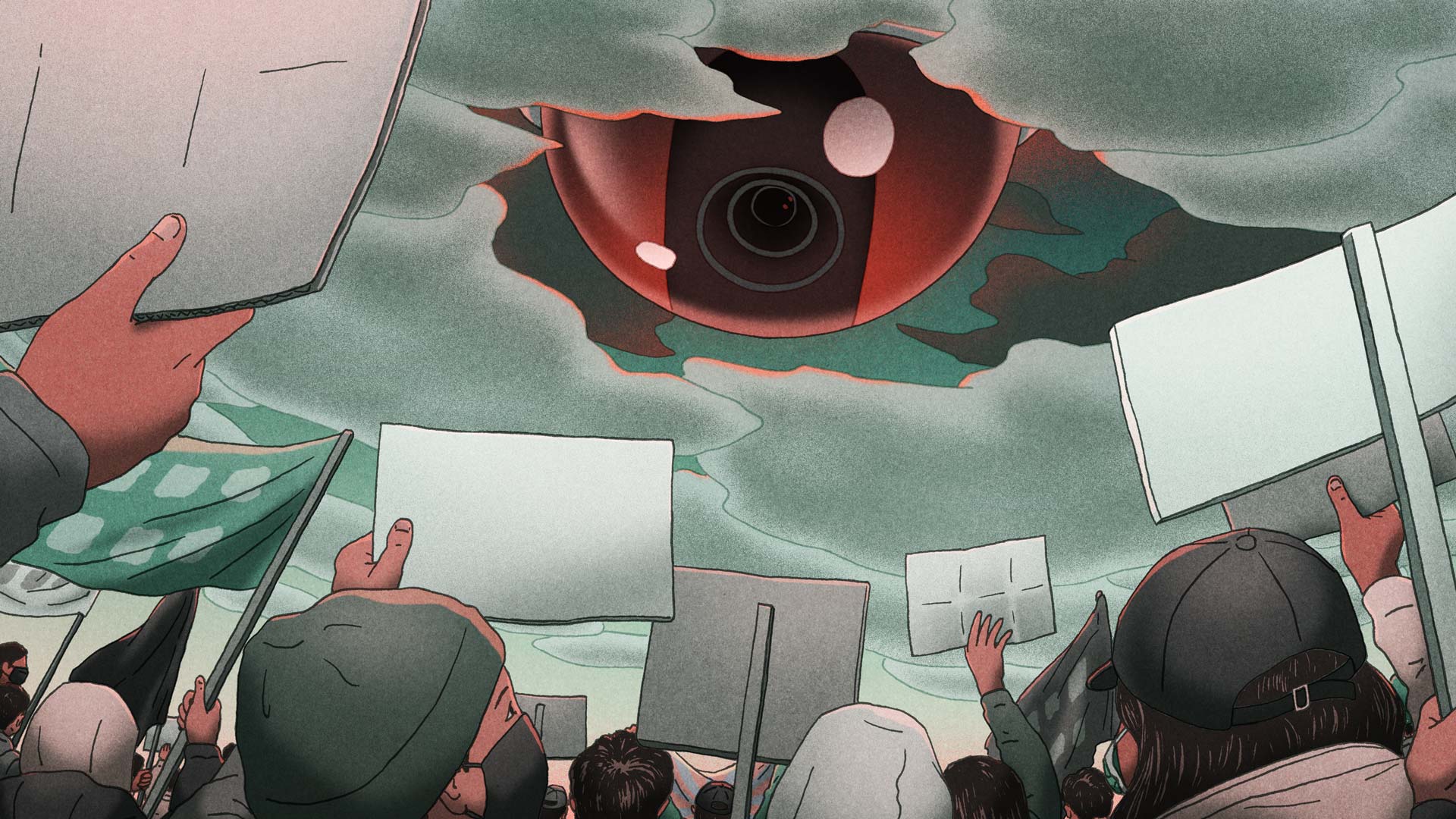

Credit: ICIJ

What remains unsaid

Technically, Dosogne hasn't broken the law. There were no formal charges, and Belgium only criminalised foreign interference in 2024. But the fact that the intelligence services took the step of warning both the man himself and his party leadership says something.

Dosogne stood as a PS candidate in the municipal elections on 13 October 2024, though due to gender balance rules, he failed to retain a seat.

Whether this marks the end of his political journey is unclear. However, what is clear is that, in a quiet town on the banks of the Meuse, a story unfolded that says much about how influence works in Belgium – not with spies in trench coats and sunglasses, but the willingness of some to believe they are simply building bridges.