The Antwerp ZOO is filled with animals — thousands, in fact — but many of those creatures, if not most of them, aren’t kept in the outdoor enclosures or the reptile house or the aviaries.

They’re stored in tiny test tubes, stowed away in a freezer, making up what may be Europe’s most important collection of biological samples to be used for zoological research.

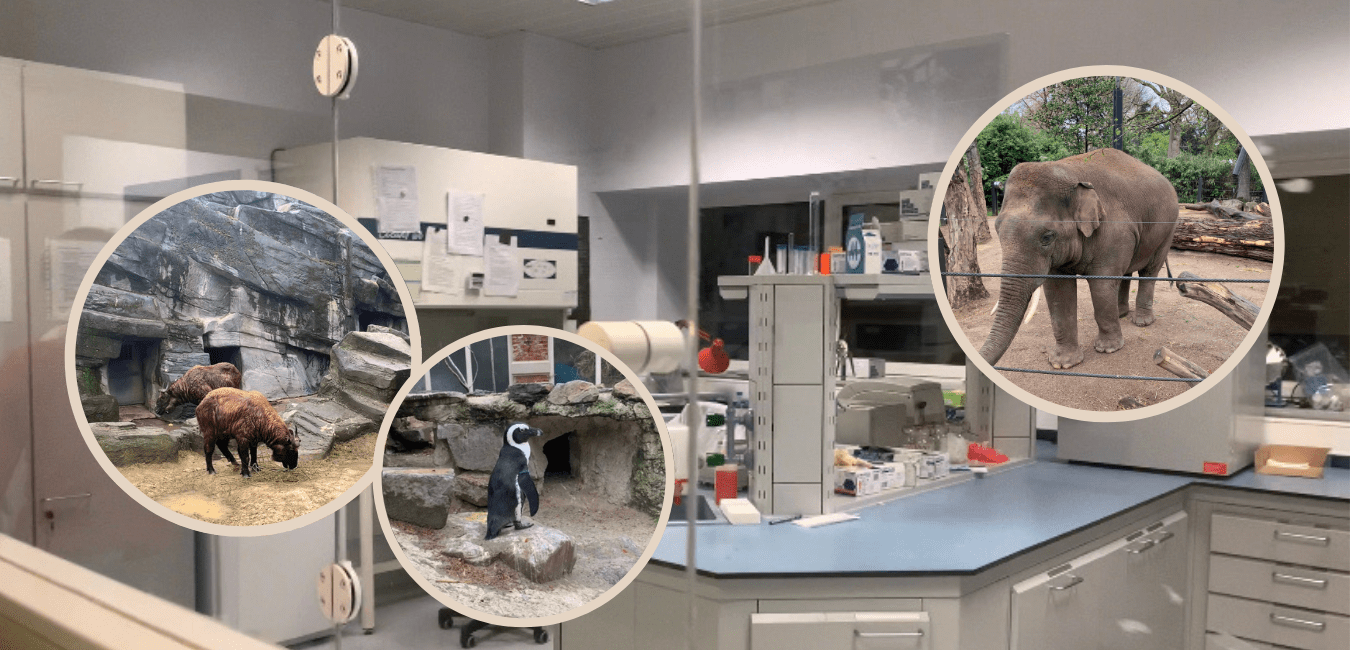

The Biobank at Antwerp is part of an initiative of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA), an organisation for the European zoo and aquarium community that links over 340 member organizations in 41 countries.

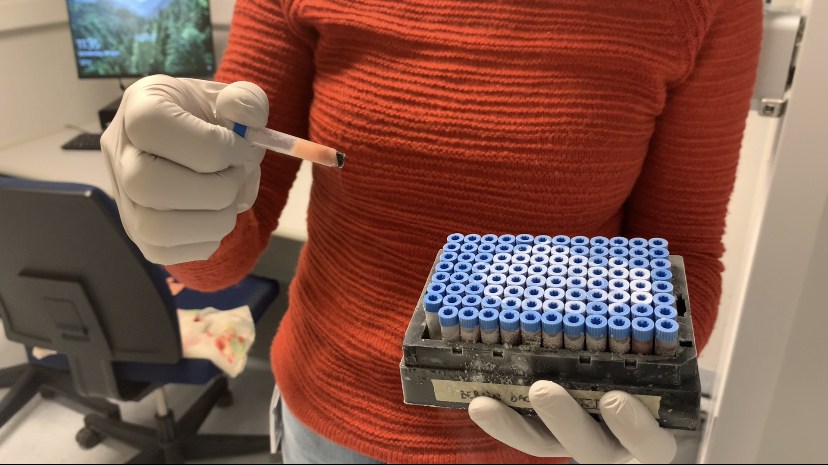

“The Biobank is a collection of samples, mostly taken within zoos, that’s added together with all the information that we have on animals,” Dr. Philippe Helsen of Antwerp ZOO told The Brussels Times.

More concretely, it’s freezers. Stored in an underground laboratory not far from where the zoo’s visitors can gather for a glimpse of Nestor the lion, the special super freezers house things like blood, gills, tissue, feathers, livers and hairs.

The purpose of such a collection of specimens is threefold: to improve the management of zoo populations through DNA research, to conserve biodiversity through the study of genetics, and, well, for science.

“The Biobank originated from frustration,” Helsen explained. “Say you have a project in mind, a question that you really want to get answered in order to make a big step forward in terms of species conservation. But then you realise: I’m not going to be able to answer that question, because it will be ages before I have all these samples.”

Collecting field samples is difficult, and not just because the gorillas in the wild are a lot less approachable than those in the Antwerp ZOO ape house. Even collecting things like scat samples (animal droppings, in plainer English) can be difficult and result in data too varied to use in research.

So scientists would turn to zoos.

“In the past, if you wanted a sample from a gorilla, you’d have to contact each and every institution to see what they had, then ask them to please send it to you,” said Helsen. “It’s a huge amount of preparation work.”

It would also mean that an animal might need to be tranquilised in order to get that sample, and if two competing scientists are conducting similar research at the same time, that may even mean tranquilising it twice.

“Now we can just say to our veterinarian, if you’re doing a routine check-up of your gorilla, and you happen to have any leftover blood samples, please send them to us and we can store them,” said Helsen.

This can also occur when an animal passes away.

“When animals die, samples can be collected and stored, in principle making the animal available for eternity. In the coming years, I think we'll see less and less frustration, because we’re building towards an unseen collection of samples people might need.”

Instead of having to reach out to hundreds of different zoos across Europe and the world, a request can be handled in one place. Antwerp ZOO is the co-initiator of the project, alongside Copenhagen Zoo.

“The goal is that a researcher would send an application to EAZA, and if approved we send them all the samples we have,” said Anaïs Claessens, a research assistant for Antwerp ZOO. “It’s much easier and more efficient.”

A glimpse into the past

While lowering the stress levels of zoologists and other scientists is indeed an added benefit, Helsen stressed that the primary role of the Biobank is to aid conservation efforts. In order to do that, older samples are studied for historical insights.

“I think the oldest samples we have to go back to the ’60s,” Helsen said.

“When exotic animals came to Belgium as historic lavish gifts to European royals and entered the Zoo’s collection, because they were so rare and so special — like, say an Okapi — once that individual died, all the remains were sent to museums. And we still know today which museums have which bones and skin.”

The result is a respectable collection of historical samples available for study, though the quality isn’t always perfect.

“There’s a huge difference between how people used to store material, and how we’re storing it now,” explained Claessens.

An animal skin in a museum, exposed to sunlight and warm, fluctuating temperatures, may provide only a handful of fractured lines of genetic code from a string of billions.

Now, samples taken today can be properly preserved in the super freezers and in liquid nitrogen.

“Instead of six animals in one freezer, we have 96 animals in one little rack, and we can have hundreds of racks in a freezer,” said Claessens. “The capacity is huge.”

So is the potential. There’s a lot to be gleaned from even the smallest amount of biological material recovered.

“We know where an individual is born, where it has been and even what it has been doing in terms of reproduction, among many other things, simply by looking at the data collected and stored over decades now,” said Helsen.

“Sometimes, however, information on who the father and the mother of that individual are — or more sporadically, which specific subspecies it belongs to — might be missing. All of that data can be gleaned from a biological sample.”

“We can do quite a lot with just a really, really small sample. It’s amazing.”

Insight into the present

Beyond providing a look into the past, the Biobank can have a more immediate impact on the present.

As of February 2020, 73 animal species are considered Extinct in the Wild, and 6,413 are classified as Critically Endangered. These animals’ existence is precarious, and protecting them is part of both EAZA’s and the Biobank’s core mission.

“Veterinary research is something that can be used to increase the viability of the captive population,” Helsen explained.

“If a disease pops up, oftentimes it’s new for science, and so we need samples to study that specific disease. In this way, the Biobank is serving the community of veterinary research as well.”

Then there’s the matter of returning animals to where they belong.

When an exotic animal is confiscated from an illegal breeder in Europe, it isn’t as simple as identifying it and sending it home, especially since the names of animal species often include the geographic location of where they were first sighted centuries ago, which isn’t necessarily indicative of everywhere they can be found.

“Say individuals were confiscated in the Netherlands, obviously not a place where they belong, but then you might have to decide: do they belong to the Mexican, Ecuadorian or even Bolivian subspecies?” explained Helsen.

“Genetic research has proven its role in pinpointing the geographic origin of specimens just by looking at the DNA profile.”

This research is also being used in the context of combating illegal ivory harvesting.

A similar investigative process takes place if an exotic animal is injured in the wild. If a bird strikes a wind turbine or some other sort of man-made obstacle in its flightpath, it’s often taken to a zoo or similar institution in order to be treated.

But once the animal is healed, in order to determine either where it was coming from or to where it was headed before being injured, scientists can again look to the Biobank for genetic clues.

A window into the future

Ultimately, the primary goal of the Biobank is to protect the animals the planet has left, including and perhaps especially those that are endangered or near extinction.

Being able to look at the genetic history of an animal through a biological sample helps conservation efforts by allowing scientists to make ideal pairings for mating that promote biodiversity and disease resistance, and perhaps undo some of the mistakes of the past that involved well-meaning zoologists breeding animals across subspecies, or even species.

“This Biobank should have been there 40 years ago, but we didn’t have the capacity, we didn’t have knowledge to do it, potentially we didn’t have the structures in place,” said Helsen.

“So it’s really nice that we’re doing it right now, and we try to also integrate the historical part and team up with museums in order to get a full picture of what these conservation breeding programs really are.”

Its reach will inevitably extend beyond just species conservation, though, as the material is made available to qualified scientists and institutions who request it for their studies.

“We hope to keep getting more and more samples, so that the Biobank can grow,” said Claessens.

“But the end goal is that the freezer is actually being emptied after a while, because researchers will ask for samples. So the samples that we collect will actually be used. We don’t want to just create a collection.”

And that’s already happening.

“What we always ask of scientists who request samples is that they come back to us with the research they’ve done, after everything is published, so that it can be embedded into the database,” said Helsen. “That way, if someone wants to do a follow-up study, we have that information.”

The result is an ever-growing body of knowledge about the Earth’s animals, a hub of which is right here in Antwerp, Belgium, not far from where Nestor the Lion is sprawled out by the waterfall in his habitat.

The Zoo is hoping he’ll become a father this year. If that happens, the cubs’ DNA will join his own in the Biobank closeby, ready for scientists to use in the fight to keep the endangered West and Central African lion from disappearing from the planet.

“It’s an investment for the future,” Claessens put it simply. “We’re basically creating a library of DNA and since it’s frozen, we can conserve it for many, many decades to come.”

“We cannot begin to imagine right now what can be done with it in 20 or 30 years, all because we’re doing it now.”