The construction of a surface storage disposal facility for radioactive waste has begun in Dessel, Flanders, with the first facility units expected to be completed by 2030.

This facility - the first of its kind in Belgium - will process low- and intermediate-level short-lived nuclear waste, including contaminated clothing, filters, resins, construction materials, certain types of medical and food industry waste.

Here, we look at how Belgium disposes of its nuclear waste and how things have changed over the past few decades - as well as examining the concerns of people living near the new disposal facility.

Moving on from the mistakes of the past

In the past, Belgium's low-level nuclear waste was thrown into the sea. In fact, the country has submerged more than 27 tonnes of radioactive waste at various sites in the Northeast Atlantic. The closest site to the European mainland is Hurd’s Deep, 180 metres deep, around 15 kilometres northwest of Cap de la Hague in France.

Containers with waste were usually dumped around 4,000 metres deep in the sea. In the Bay of Biscay sites, they were placed 300 to 550 kilometres offshore from the French and Spanish coasts. This practice persisted until the early 80s, when it was banned due to concerns about the environmental impact of nuclear dumping.

“If I have a can of Coke, I don't throw it away in nature. So, it's the same principle. And with the surface disposal, we have control over the whole process of getting rid of that waste,” explained geologist Laurent Wouters, who has worked for the National Agency for Radioactive Waste and Enriched Fissile Material (NIRAS/ONDRAF) for more than 30 years. NIRAS/ONDRAF is responsible for the safe management of all radioactive waste in Belgium.

After sea disposal was banned, Belgium began storing its nuclear waste in buildings at a Belgoprocess site. Sometimes it was burned.

“But that's not a long-term solution," said Wouters. "After 100 years, buildings get old, and you have to build a new one. But then you have to move all the waste to the new building. And that's also a risk.”

Surface disposal

The type of waste that will be stored in the new Dessel facility contains far lower radiation levels than high-level waste. Belgium is still investigating how to dispose of its high-level radioactive waste, which is currently managed at nuclear sites.

Low-level waste mainly originates from the dismantling of nuclear power plants and other nuclear facilities, but also from hospitals, industry, and research institutions.

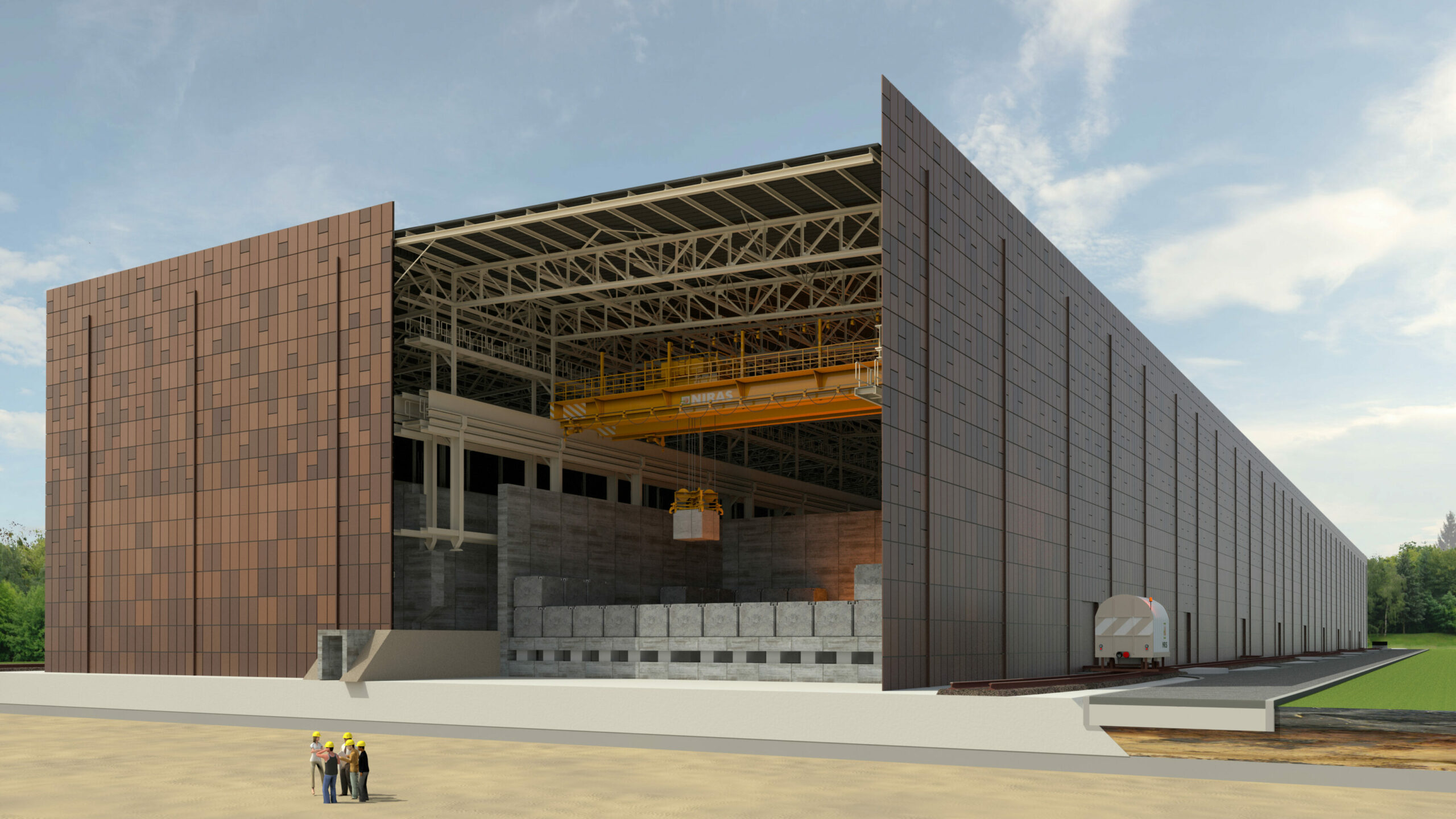

The storage facility, hosted by Belgoprocess and coordinated by NIRAS/ONDRAF, will consist of concrete bunkers, each holding large concrete containers in which the radioactive waste will be encapsulated with mortar. It is designed to store all existing and future low- and intermediate-level short-lived waste in Belgium.

The facility was inaugurated by Belgian Prime Minister and site manager Rudy Bosselaers on 18 September, 2025. Credit: NIRAS/ONDRAF/Kristien Mertens

The disposal will take place over a period of 50 years. Afterward, the facility will be permanently sealed with natural and artificial layers to protect against water infiltration, creating two green hills of about 20 meters high. The site must then be preserved and monitored for at least 300 years.

“It's not the first disposal facility in the world, of course,” said Wouters. “We looked at other countries, and we took their best concepts. For example, the concept of cemented monoliths with waste comes from Spain."

As part of the conditions imposed on the storage facility by the city, the site will feature a 60 centimetre cellar underneath the facility for visual inspection of the waste by a robot with a camera. Before the start of the construction, scientists and engineers looked into the worst-case scenarios in case of an accident, such as if the concrete and the earth layer are destroyed after 300 years.

Scientists have accounted for this eventuality, calculating the dose of radiation that would go into the groundwater and into the river. This calculated dose must remain under a dose rate, set by the Belgian safety authority.

But even with a total destruction of the disposal, dose limits stay under the threshold. “If there is a leak, we can do something about it and remediate. The [radiation] levels are so low that even with a leak, it’s not a problem,” said Wouters.

He does not know exactly what will happen over the course of three centuries, but said the current plan is to leave waste under the ground. “Normally, when you do disposal, you don't have the intention to move it again afterwards. It will be covered by soil. And all these layers will protect the concrete underneath against water infiltration and contamination,” he explained.

Residents mostly sanguine - but some concerns remain

On the streets of Dessel and nearby Mol, residents were generally relaxed about the construction of the new Belgoprocess storage facility. Dessel has, after all, been host to other nuclear facilities for many decades.

Dessel resident Marc Van Den Ackerveken, 63, said the local population would benefit from the new site. “The nuclear site is more than 60 years old. And I think that all the knowledge that we have about it must stay here in this region. When it’s not here, it’s somewhere else. It should stay in Belgium,” he explained.

A woman in her 30s we spoke to was similarly sanguine. “There is much worse stuff than radiation, like smoke and CO2. We have to live with it," she said.

Others raised concerns about safety, however. Lowie Janssens, 27, said: “People are getting a lot of money, but is it safe? I don’t know. I have many questions. For example, what will we do with it in 300 years, and what will be its impact?”

A 19-year-old man, who wished to remain anonymous, argued that while things could go wrong, "if something happens, it happens". He added: "we cannot do anything about it - if we get sick, we get sick.” The man did, however, say he was comforted by Belgium’s strict safety rules.

The planned hazardous waste storage facility in Dessel, Flanders. Credit: NIRAS/ONDRAF/Kristien Mertens

'A stable setting for the repository'

NIRAS/ONDRA have provided assurances to residents that the facility is safe and say they have taken care to protect the local environment.

Sigrid Eeckhout, a spokesperson for the organisation, said: “Thanks to the chemical and physical properties of the barriers, concrete and mortar retain radioactive materials and limit water infiltration. They thus prevent radioactive materials from leaching into the environment.”

"Moreover, the concrete is composed in such a way that its degradation will occur very slowly over the centuries. The disposal site has been duly characterised in terms of stability, level of seismic activity, bearing capacity, location outside of possible flooding area, etc. It will thus ensure a stable setting for the repository.”

According to NIRAS/ONDRA, safety reports will be published on the FANC website (Federal Agency for Nuclear Control) to ensure full transparency.