An international group of scientists, including from Belgium, have found a new method that can predict stealth coronal mass ejections (CMEs), a type of solar storm, occurring on the Sun's surface, helping to prevent them from causing damage on Earth.

Most of the Sun is in a charged plasma state, which means the gas is highly ionised, and when such a cloud is ejected by the sun, it is called a plasma cloud or CME.

"Stealth CMEs have always posed a problem, because they often originate at higher altitudes in the Sun’s corona (the outermost part of the Sun's atmosphere), in regions with weaker magnetic fields," author Dr Erika Palmerio, a researcher at the Space Sciences Laboratory of the University of California at Berkeley, said in a press release.

"This means that unlike normal CMEs – which typically show up clearly on the Sun as dimmings or brightenings – stealth CMEs are usually only visible on devices called coronagraphs designed to reveal the corona," she added.

Without spotting CMEs, it is impossible to predict where on the Sun it came from, "so you can’t predict its trajectory and won’t know whether it will hit Earth until it's too late," Palmerio said.

Continuous, smaller danger

The last time a CME posed a potential threat to people on Earth was just over nine years ago, in July 2012, when an enormous, diffuse cloud of magnetised plasma, tens of thousands of kilometres wide, was ejected by the sun at a speed of hundreds of kilometres per second.

In this case, the CME just missed the Earth because its origin on the Sun was facing away from our planet at the time, however, if it had hit the Earth, it would have disabled satellites, power grids around the globe would have been knocked out, GPS systems, self-driving cars, and electronics jammed, and railway tracks and pipelines damaged.

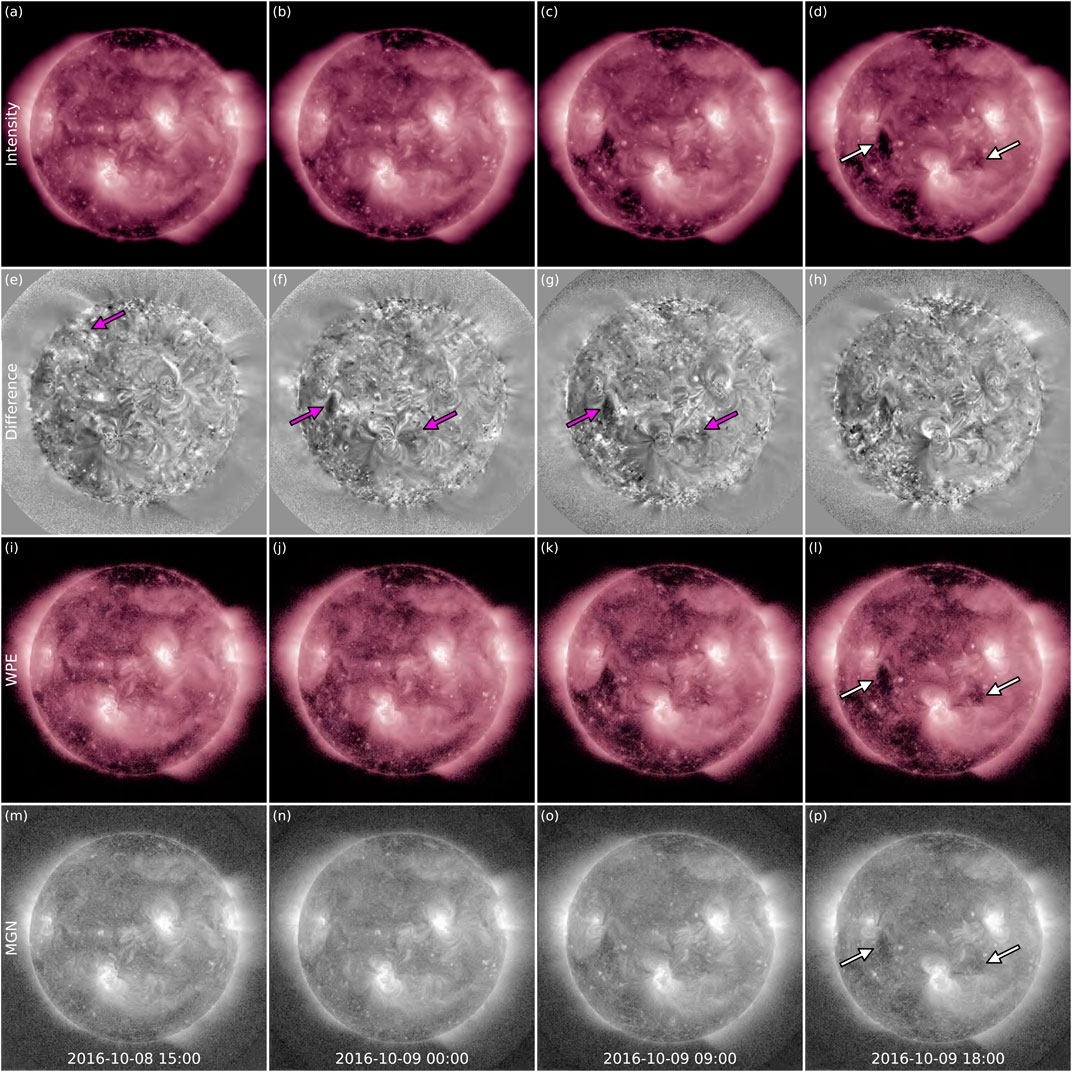

The new imaging techniques were applied to remote sensing data of the coronal mass ejection on 8 October 2016. Credit: Palmerio, Nitta, Mulligen et al

The cost of the potential damage of such a large-scale CME has been estimated at between €500 billion and €2.2 trillion in the US alone.

The Earth is impacted by lesser versions of CMEs once every three years, and as the CMEs take around more than one day to reach our planet, the technique could give humans time to prepare for the potential geomagnetic storm.

The scientists, including Marilena Mierla and Andrei Zhukov of the Royal Observatory of Belgium, have said the technique, which will help in taking measures to limit damage to electronics and power grids on Earth from the electromagnetic radiation of such eruptions, can be applied immediately.