When people think of countries facing water crises and water shortages, Belgium is probably not the first to come to mind, especially considering the floods that affected the country on 14 and 15 July.

However, for the last few years, Belgium has faced a water scarcity problem that has a lot to do with the very issue that, in part, caused the floods: climate change.

Meanwhile, people's lifestyles are increasingly making matters worse.

What is Belgium's problem?

The water crisis faced by Belgium (and some other western countries) strongly differs from the issue faced by developing countries, Marc Van Molle, professor in physical geography at the Vrije Universiteit Brussels (VUB), told The Brussels Times.

The problem of water scarcity in these countries, mainly located in the southern hemisphere, is often the result of socioeconomic conditions. Belgium, on the other hand, is facing a shortage of water due to insufficient or irregular precipitation.

This "physical water scarcity" affects about 20% of the world's population, around 1.4 billion people, and in Belgium, has lead to the country risking running out of tap water during dry periods.

100 bathtubs of water per day

Belgium's "water footprint" is the most under-reported aspect of the problem, but is also one of the biggest factors causing its water scarcity issue, according to Van Molle.

"On paper, the average person living in Belgium consumes around 120 litres of drinking water per day for drinking, cooking, washing our hands, etc, however in practice, this is much more," he explained.

In Belgium, people's total water footprint amounts to 7,400 litres per day, which is the equivalent of almost 100 bathtubs, and over double the water usage of an average world citizen.

As it only has the capacity for about 2,300 litres of water to be used per person per day, Belgium depends on other countries for more than two-thirds of its daily water consumption.

"Therefore, we also have a major impact on water scarcity in other countries, from Spain to Pakistan, where water scarcity is much higher than average," Van Molle added.

When looking at what most of this "virtual or invisible water consumption" is used for, it becomes clear that the production of goods that are part of our lifestyle makes up the biggest part.

"Agricultural products - which includes food but also the production of natural fibres for textiles and wood for constructions - absorb the largest share (94.6%), followed by industrial products (3.2%) and direct household use (1.2%)," he said.

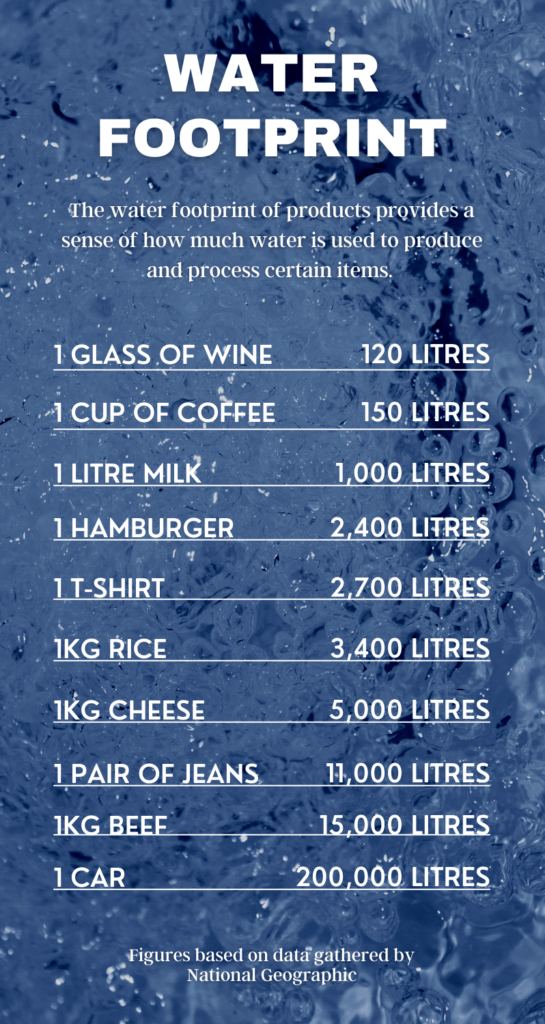

Calculating the water footprint of products based on industry data provides a sense of how much water is used for certain products or processes, including all the water used to grow edible crops for humans and animals, process food, and clean up pollution caused by the food production system.

As a result, the conventional recommendations of showering less frequently, watering the lawn and flushing the toilet less will have a small impact on Belgium's water consumption, but won't solve the bigger problem.

According to Van Molle, changing consumption patterns as well as slowing down and then stopping global warming are the main solutions for the water scarcity problem affecting Belgium.

Scarcity vs. flooding?

Research, including that of Van Molle, shows that climate change will only aggravate water scarcity, as for every degree that the earth warms up, an additional 7% of the world's population will see their freshwater supply reduced by 20%, whilst evaporation will increase by about 3%.

One result of this problem is already being felt in Belgium, as at the start of June last year, more than 80% of the water measuring sites in Flanders showed low to very low groundwater levels, but this will also result in the earth's water cycle "firing up", causing intense and localised precipitation.

This may seem positive when thinking that Belgium suffers from water scarcity, but this is far from the truth, as July's fatal floods have proven.

"Heavy precipitation only penetrates a little or not at all into the ground, and thus does not feed the groundwater, but instead runs off at the surface. Very often we see the "water" - a combination of rain and soil - flowing through streets," he explained.

This type of rainfall also results in soil washing away, which results in there being less vegetation, and therefore even more erosion occurring during the next storm. "A vicious cycle," Van Molle warned.

As a result of the previous wet months - of which July was the wettest on record in 40 years - groundwater levels in three out of four measuring stations in Flanders returned to normal to very high in June, but a quarter of them continue to indicate that the groundwater levels are low.

"Even today, they are far from having recovered to levels that would allow us to use tap water without concern," said Van Molle.

Rain in Belgium is, at best, unpredictable and irregular. Although certain projects are being launched, more initiatives are needed to allow precipitation to infiltrate the ground, purify more water and reuse purified wastewater, according to Van Molle.

"The measures needed to achieve this are well known. Implementing these measures as soon as possible is the best thing that can be done. If this can't be done, there is not much else one can do but try to limit the damage."