Not every Belgian beer style has survived the march of time.

Some have disappeared as casualties of war, regulation, or changing work patterns; others have succumbed to industrial pressures or consumer shifts. But in recent years, brewers have tried to revisit styles that history nearly erased.

Seef or Seefbier, for example, once the pride of Antwerp, vanished with the collapse of small urban breweries during the First World War.

A decade ago, Johan Van Dyck claimed to have uncovered an old recipe for a seef beer which he reincarnated with a barley, wheat, and oat grainbill and a creamy, unfiltered profile. In recreating it, Van Dyck reignited city pride with a new generation of drinkers.

In Lier, the brown-amber ale caves was revived by a local heritage guild, which commissioned it to be recreated from archival recipes (but only for serving in cafés within the town walls). And then there’s uitzet, a mixed fermentation brown ale from East Flanders that local brewers such as DOK Brewing Co, have tried to recreate in Ghent.

Through detective work in old brewing manuals and oral histories – and some creative marketing from those keen to tell stories that will spark consumer interest – modern brewers have sought to revive identities and walk the line between innovation and heritage.

Grisette: The miner's refreshment

Grisette is a traditional Belgian beer style said to have originated in the Hainaut province during the late 18th century. It is often said to be the industrial cousin of the saison style, another Hainaut beer created for the sustenance of farmworkers during harvest off-seasons.

If saison is the farmstead beer, then grisette is the beer of Walloon coal mining. The name grisette references the grey dresses of the women who are said to have served beer to the miners.

Grisette may have been lightly hopped, heavy on wheat, and possibly underwent open fermentation, resulting in beers that may have been dry, highly attenuated, effervescent, and with subtle tartness.

Modern interpretations often remain true to a perceived low alcohol content, typically between 3% and 5% ABV, and try to maintain the use of wheat. Some brewers incorporate spices or fruit, and fermentation is usually carried out with saison yeast strains to replicate the dry, crisp character.

An old Grisetter beer advert

As such, modern grisette is characterised by its light body, high carbonation, and refreshing nature. Flavour profiles typically include a citrus, herbal, or spicy aroma, notes of lemon, wheat, and a mild tartness, with a dry, effervescent mouthfeel.

The most celebrated modern interpretations of grisette come from Brasserie St-Feuillien, a family brewery in Le Rœulx, which produces Grisette Blanche Bio (5.5 % ABV), Grisette Blonde Bio gluten-free (5.5 % ABV), and Grisette Citra Hop Bio gluten free (8% ABV).

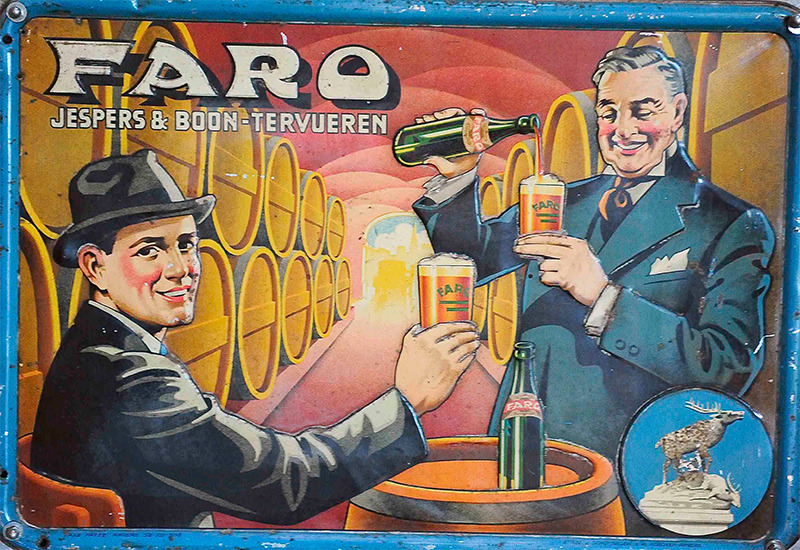

Faro: Belgium’s sweet-and-sour heritage ale

Faro emerged as a beer style of the lambic family in 18th century Brussels. It was known for its affordability, lower alcohol content, and suitability as an everyday drink for the working class.

Faro was often sweetened with brown sugar or caramel to balance the acidity inherent in lambic beers. Its popularity declined in the 20th century with the rise of pilsner-style beers, but it has seen a resurgence in recent years due to renewed interest in traditional and regional beer styles.

An old Faro print advert

Sugar was usually added just before serving in the café or home, right before drinking, to prevent the likely refermentation that would have occurred had the sweetener been added in the tank or package (with the inherent risks of over-carbonation).

Today, faro is produced by blending lambic with sugar in production facilities and then pasteurising the beer to prevent further fermentation. Common tasting notes include fruity aromas such as apple and pear, with hints of caramel, and a sweet and sour taste featuring brown sugar, green apple, and wild yeast character.

The most well-known modern faros come from Belgium’s lambic breweries. Brouwerij Boon of Lembeek produces a faro that blends old lambic with Meerts beer (a lighter version of lambic) and candy sugar.

Brouwerij Lindemans of Vlezenbeek began producing faro in 1978 as part of their effort to revive traditional lambic styles. Their version is sweetened with sugar syrup. And Brouwerij Timmermans, one of the oldest lambic breweries in Belgium, continues to produce Faro as part of their commitment to traditional beer styles.

Peeterman: Leuven’s lost oat ale

Peeterman was a traditional beer style originating from Leuven, Belgium, named after the city's patron saint, Saint Peter (the term Peeterman was also a nickname for the inhabitants of Leuven).

Historically, Leuven was renowned for two primary beer styles: white beer (witbier), famous today globally, and Peeterman, a stronger and slightly darker variant of the white beer, known for its cloudiness and sour taste.

Peeterman was a hazy, sour beer brewed using wind-dried barley malt, unmalted wheat, and oats. It was most likely fermented spontaneously or with wild yeasts. It disappeared in the early part of the 20th century, one of the many victims of the rise of lager.

Pierre Celis and his Hoegaarden brand later revived Witbier, but Peeterman quietly exited stage right.

An old Peeterman beer advert, a darker form of the famous Wietbier

AB InBev, whose headquarters are in Leuven, released a Peeterman Artois in the 2000s, but it was withdrawn in 2008, presumably due to lack of interest.

This may have been because they didn’t lean into the style’s history, producing what was essentially a 4% ABV wheat lager rather than the hazy, sour beer featuring unmalted wheats, oat, and wild yeast that was the Peeterman.

Brouwerij Breda, a small Leuven-based contract brewery, released a contemporary Peeterman-esque wheat ale in 2019 (6% ABV, unfiltered), but the style remains a curiosity to this day, fondly remembered, but not yet reborn.

Gruut: The medieval herb ale

Before hops were the dominant bittering agent in beer, brewers in Belgium relied on a mixture of herbs known as "gruit" ("gruut" in Flemish) to flavour and preserve their beers: bog myrtle, yarrow, and wild rosemary, among others.

When hops arrived in the 14th and 15th centuries, it was clear that they had superior preservative and bittering qualities.

International brewing regulations, such as the German Reinheitsgebot, mandated the use of hops. Soon, hops had taken over from gruit herbs in the mainstream production of beer.

In modern times, Brouwerij Gruut — with a brewbar location in Ghent (but brewing larger production volumes in Brouwerij De Brabandere in Bavikhove) — produces a range of beers that deploy a blend of herbs instead of hops, including Gruut Wit, Blond, Amber, Bruin, and Inferno.

Gruut beer

Brasserie Dupont of Tourpes has its Posca Rustica, a beer the brewery describes as Cervoise beer, spiced with a gruit herb mixture. Sweet woodruff and bog myrtle are just two of a dozen different spices used.

Bog myrtle is also used as a single herb in the beer Gageleer, produced by a nature conservation cooperative of the same name from the Kempen region but brewed at De Proefbrouwerij in Lochristi.

The owners say bog myrtle is a shrub that grows on peaty soils, such as in the nature reserves of the Kempen region, and as such is a fitting herb to define their historically-inspired beer.

What comes back

It’s all too easy to get wrapped up in the romance of revived versions of historical styles. But these beers — grisette, faro, gruut, Peeterman, seef, uitzet, and caves — don’t return whole. They come back in fragments.

They bear the fingerprints of the modern brewers who have attempted to translate them into the 21st century, the limitations of contemporary equipment, and the compromises of shelf life and sales.

Their return doesn’t restore a lost golden age. But it does suggest that even in a modern brewing culture shaped by fast-moving commercial trends and competitive export markets, there’s still room for beer styles with roots that speak of a particular moment in time, in a particular place, and a particular people.