When new photos and footage of Jeffrey Epstein’s infamous private Caribbean island were released by US politicians last week, one detail caught the eye of this Belgian observer.

Near the abandoned swimming pool once owned by the disgraced late financier and convicted sex offender was an elegant bronze figure of an African man drawing a bow.

This is a statue familiar to many in Brussels. It is a copy of L’Archer (The Archer) by the Belgian sculptor Arthur Dupagne – the very same work that stands, somewhat unobtrusively, on the junction between Place du Quatre Août and Avenue du Front in Etterbeek, just a few steps from the Thieffry metro station.

In Brussels, The Archer is a known if understated landmark, tucked into the urban fabric of a commune that hosts EU civil servants, students and diplomats. First crafted in 1936, it exemplifies a colonial-era artistic tradition that idealised African figures, presenting them as muscular, heroic and timeless. For years, debates have surfaced about whether the work should remain in public space without contextualisation.

The Archer is one of the most prominent surviving examples of Belgium’s Africanist colonial art. Dupagne, born in Liège in 1895, spent eight formative years in the Kasai region of the Belgian Congo as an engineer for the mining company Forminière. There he became fascinated by local statuary traditions – particularly those of the Chokwe – and by what he saw as the “vigorous plastic beauty” of the people around him. He modelled dozens of clay studies of Congolese villagers before returning to Belgium in 1935 to devote himself fully to sculpture.

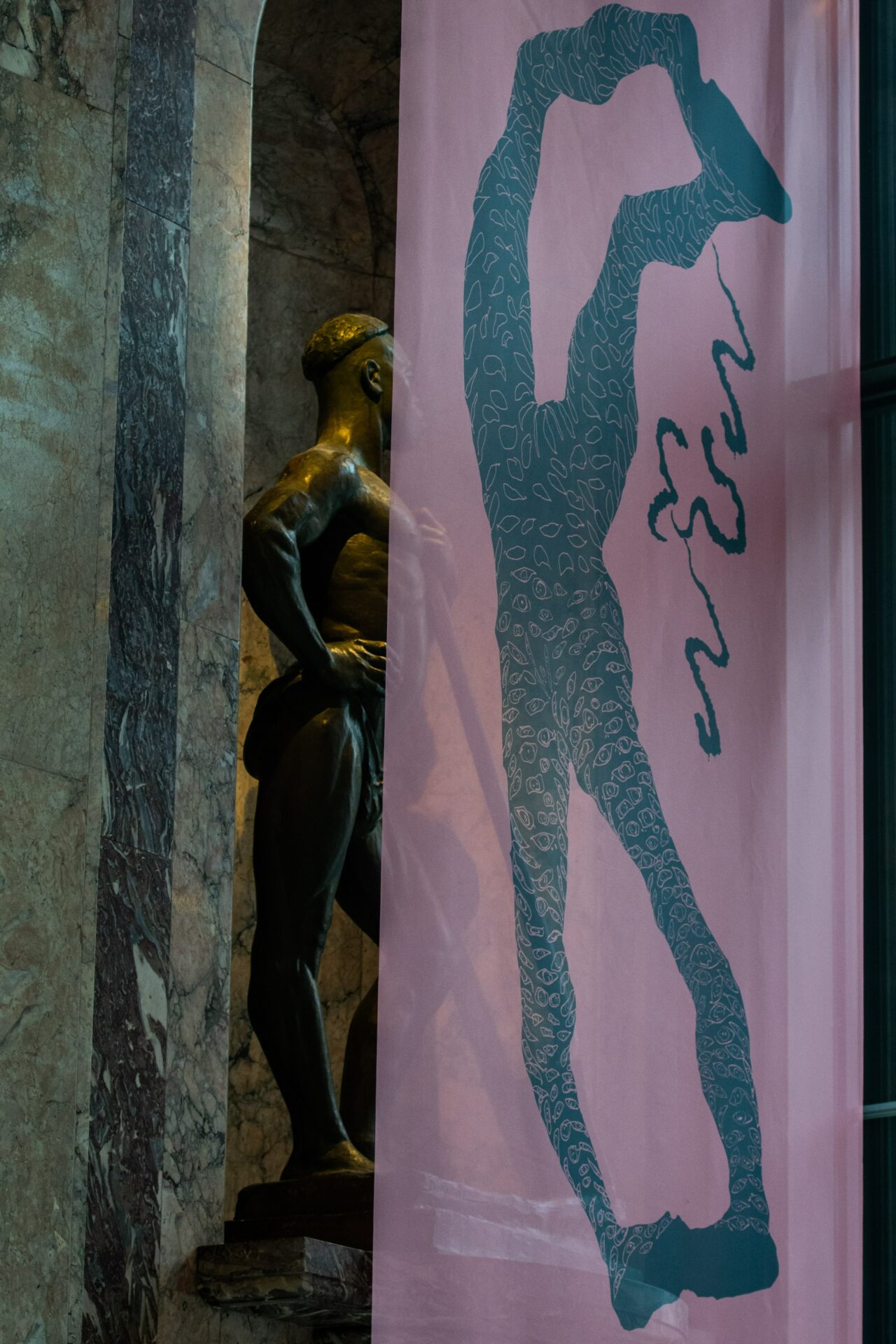

L’Archer (The Archer) by the Belgian sculptor Arthur Dupagne

Exhibited at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair, Dupagne’s Archer shows a young African man crouched in an extreme pose, bow tensed, muscles exaggerated to near-bodybuilder definition. The original plaster model now sits in Liège’s Musée de la Boverie. The bronze in Etterbeek was cast after Dupagne’s death in 1961 and inaugurated in June 1962 as a family donation to the municipality, its pedestal describing the work simply as a “gift”. That was a full two years after Congo achieved its independence from Belgium.

Yet for all its technical skill, Dupagne’s sculptures are controversial. He was one of many artists who underpinned Belgium’s African rule in stone and metal sculptures. Others include Thomas Vinçotte, Charles Samuel and Arsène Matton. Their artworks, like the monumental Congo Panorama painting, aimed to project a positive image of European action in Africa.

“Their craft implied Europeans being in a position of observer, with the means, time, and resources to scrutinise the foreign ‘Other’,” says Matthew Stanard, a history professor and author of The Leopard, the Lion, and the Cock, a book about colonial monuments in Belgium. “In this way, such ‘colonial’ or Congo-inspired art asserted the European over the African; the artist over his subject matter; the master over its subject.”

Six other Depagne statues are in the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, where they cannot be moved because the building, known now as AfricaMuseum, is a protected monument.

All these statues exemplify the colonial-era trope of the African as a heroic yet primitive archetype – the “noble savage”. Though in this case, AfricaMuseum director Bart Ouvry notes, “more savage than noble.” Ouvry says the statue is unambiguously stereotypical. “The African man is depicted like wildlife: dehumanised, reduced to his physical self,” he says.

While it is hard to know how a copy of the statue ended up on Epstein’s island, Ouvry hints at a reason why. “In a way, it’s fitting to see the statue on his property,” he says. “Epstein was, after all, someone who saw people as objects.”

Illustration picture shows the inauguration of the renovated 'Roundabout' (De Grote Rotonde - La Grande Rotonde) at the AfricaMuseum, which houses Arthur Depagne's sculptures. Credit: Belga

AfricaMuseum had an instructive reckoning with the statues. The museum was first built by King Leopold II for the World’s Fair 1897 to house the artefacts looted from Congo, but in recent decades it has taken into account criticism that it glorified Belgium’s colonial past, not least by a visiting UN working group on people of African descent in 2019.

“That’s when we realised something had to be done,” Ouvry explains. When the museum was reopened in 2020 after a long refurbishment, the Dupagne sculptures were partly covered by curtains and given explanatory texts to signal that, while the works remain, they no longer stood unexamined or unchallenged.

Other Belgian institutions and administrations also began looking at their colonial era monuments, notably in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, which targeted problematic statues in Britain and in the US in 2020.

L’Archer (The Archer) by the Belgian sculptor Arthur Dupagne

However, many remain in place, including the Leopold II statue next to the Royal Palace in Brussels, and The Archer in Etterbeek. In October 2023, Etterbeek mayor Vincent De Wolf agreed to the recommendations of a special 18-month communal committee that called for colonial monuments in the public space to include clear contextualisation. But more than two years on, The Archer remains in place without any added explanations.

The link with Epstein’s island does not necessarily make the Brussels version inherently more controversial, but it does underscore how objects travel – stripped of context, repurposed, reinterpreted.

In Etterbeek, the statue stands in an ordinary streetscape, mostly unnoticed unless one knows where to look. On Little Saint James, it was part of a curated, uncanny landscape designed to project wealth, power and mystique.

For Belgium, this moment offers an unexpected opportunity: to revisit how colonial-era artworks are displayed, explained and understood. The Archer is no longer just a Brussels curiosity. It has become a reminder that even the most familiar statues carry histories far beyond their plinths.

Related News

- The Congo painting that Belgium can never show again

- Belgium’s failed, forgotten Caribbean colony

- Belgium to pay tribute to Congolese soldiers of 1914-1918 for the first time

- A water leak is causing a risk of road collapse on a Brussels street

- Most Flemish mayors say they cannot handle local safety problems, survey finds