Brussels' working group on the decolonising of public spaces in the region on Thursday presented its plan for systematic interventions which will start by the end of 2022.

The task force, set up in September 2020, researched, reflected on and debated the presence of colonial symbols in public spaces in Brussels for 15 months, and wrote a report based on its findings, offering a series of recommendations for the Brussels government.

"The voluminous report that the working group presented will be submitted to the Brussels Government and the members of the Brussels Parliament. On the basis of this report, both a parliamentary and a social debate will follow," State Secretary for Urbanism and Heritage Pascal Smet said in a statement to The Brussels Times.

Elements that emerge from this debate will be combined with the recommendations to form an action plan, which will again be submitted to the government around September.

"We will make concrete decisions on how to decolonise our city. The first interventions in the street scene will follow by the end of this year," Smet said.

A Brussels that represents all inhabitants

The group stated that, since the end of the 19th century, the region's public space has been "shaped by interventions created from a one-sided and propagandistic perspective" which it argued did not take into account the presence of colonised people and their descendants living there.

A defaced monument of Lt-gen Émile Pierre Joseph Storms in Ixelles. Credit: urban.brussels

"Today, this public space no longer reflects the vision of the current inhabitants of Brussels, as the activist mobilisations over many years have shown. What used to be normal, is no longer normal today," the report stated.

The monuments and place names at the heart of the decolonisation discussions today are just a fraction of the colonial traces in the public space, the task force found, stating that various sites and buildings in the region are also marked by the historical relations between Belgium and Congo, Rwanda, and Burundi.

For example, many of the grand buildings and structures in the region, including the Palais de Justice and the arches in Parc du Cinquentenaire, were funded by the sales of ivory, rubber and timber plundered during King Leopold II's ruling over Congo.

Monuments, street names and buildings

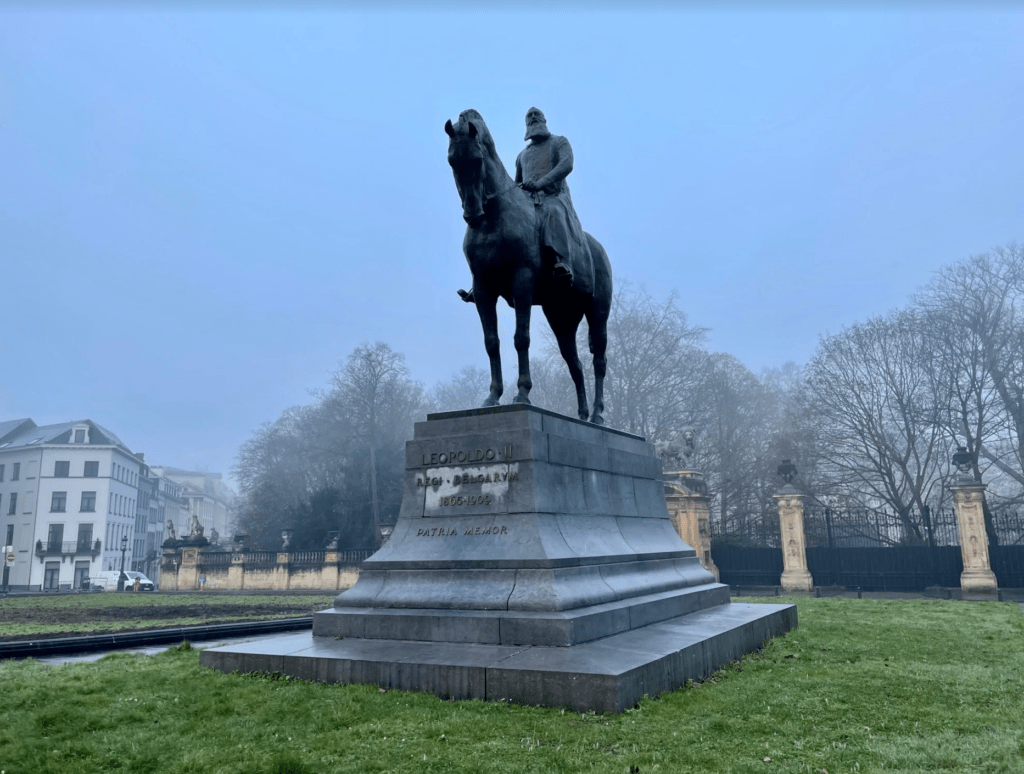

Among its recommendations, the working group targets the equestrian statue in honour of King Leopold II near the Trône metro stop. It stated this should either be removed or radically transformed into a memorial for the victims of colonisation, as this is "the most symbolic and controversial location" (due to its presence near Matonge, a largely African neighbourhood in Brussels).

Alternatively, it could be moved to a dump for discarded statues, leaving the empty plinth as a space for temporary artistic interventions. It also proposed the creation of such colonisation memorials in Parc du Cinquantenaire, where it suggested colonial statues will be moved and collected.

Related News

- Confronting Leopold’s Ghost

- How history can help us understand the rage against statues

- Inventory of 85,000 objects from Afrikamuseum handed over to Congo

The working group stated that, as street names have a greater influence on the lives of residents than monuments, all streets, squares, stops and tunnels that refer to so-called “colonial heroes" should be renamed to represent people of colour linked to Belgian colonisation.

"This marks a historic opportunity to achieve a more balanced representation in terms of gender, origin and themes in the public space."

Re-appraising rather than overwriting history

Aside from these structural changes, the working group stressed the importance of recognising the legitimacy of contesting colonial monuments throughout the entire process, and creating a general awareness of the implications of colonisation and its consequences, mainly through education about the history, and a colonial period remembrance day.

"Through its current role as capital, Brussels can serve as a starting point for an introspective work of remembrance," the report concluded.