During the Second World War, some 25,000 Jews were deported from Belgium to Nazi death camps. Almost all were despatched on trains from the same place, Mechelen’s Kazerne Dossin army barracks. Now a museum and memorial, Kazerne Dossin is a sobering yet vital site.

You can’t miss the Stolpersteine or stumbling stones. They are all over Europe. Placed in the pavement, these small brass cobblestones mark the houses where Jewish people and other victims lived before they were deported to Nazi death camps.

The first stone was laid by the artist Gunter Demnig in 1995 in Berlin’s Oranienstrasse. He simply dug a small hole in the pavement, placed an inscribed brass stone and cemented it in place. ‘Hier wohnte’ – Here lived, it read, followed by a name, a date, a place of death. One year later, Demnig placed a further 55 stones in Kreuzberg district as part of an art project dedicated to the Holocaust. Now there are over 7,000 Stolpersteine in Berlin and more than 70,000 scattered across Europe. They surprise you – as they are meant to do – as you are wandering in Trondheim, Antwerp, Prague and Budapest.

The stones began appearing in Brussels in 2009. Now they are embedded in pavements all over Belgium. But the largest concentration is in the Marolles district. Sometimes you see a single stone. Other times, a cluster of several.

Outside Rue Haute 173, there are 16 stones set in the pavement marking Jewish refugees from Germany and Poland who had fled to Belgium in search of a safe haven. Further down the street, eight are set in the pavement outside a Lidl supermarket. These small markers are quiet reminders of people who once walked the streets of Brussels before their lives were brutally interrupted.

Almost every memorial stone in Brussels has the words ‘Détenu Malines’. Held in Mechelen. That was the last stop in Belgium for most of them. The Kazerne Dossin army barracks on the edge of Mechelen held more than 25,000 Jews and several hundred Roma before they were put on trains to Auschwitz and other camps. For many years, Belgians were hardly aware of this dark period in Mechelen’s history. But that changed in 2012 with the opening of the Kazerne Dossin museum.

Images, voices, stories

Facing the former barracks, Kazerne Dossin museum occupies a sober modern building with blacked-out windows designed by Antwerp architects AWG led by Bob van Reeth. The museum aims to tell the history of the Holocaust using photographs, documents, video interviews and historic objects.

It is not an easy place to visit. It could not be otherwise. The first thing visitors see is an enormous photo wall that rises through four floors. It is covered with 25,000 official passport photos (or silhouettes, where no photo has been found) to represent the people who passed through the barracks. Every year, new photos are uncovered. They are added to the wall in an annual ceremony. In 2021, more than 50 new faces were found to fill more of the gaps.

A large section of the museum is given over to the 25 train convoys that left from Mechelen, each carrying more than 1,000 people. In a series of small rooms, the details of each convoy are listed. How many were taken. How many survived until the end of the war. The figures are brutal. And to add to the pain, there are photographs of some of the victims. Not passport photographs this time, but family snapshots from before the war. Two smiling girls. A mother pushing a pram. A couple on a café terrace.

The museum has carefully pieced together some individual stories using small objects that somehow survived the war. They include drawings, children’s toys and confiscated possessions. The museum has also gathered a collection of scribbled letters and postcards that victims threw from the trains as they were taken off to an unknown destination (Holland, they were often told). The letters carry desperate final messages for relatives back in Belgium. The last post, the museum calls them bleakly.

In 1942, Jeanne Roosen, aged 17, came across a postcard lying next to the tracks near Tienen. It was thrown from the train by Moïse Iarchy as he was being transported to Auschwitz. Risking her life, Jeanne posted it to Moïse’s wife, who survived the war along with her son Jean. He came across the postcard many years later, after his mother died. Jean Iarchy got in touch with Jeanne Roosen’s relatives, and the two families met for the first time in 2021.

Rachel Mandel and Israel Isaak Lipschitz

Displayed in a glass case, two small objects tell a rare story of heroism. A fake emergency lantern and a small pistol were used by three young students to stop the Transport XX train carrying 1,600 Jews to Auschwitz. More than 200 people escaped.

Some didn’t get far. A photograph taken after the attack shows a young girl shot dead by the guards, just moments after she escaped. The authorities had no way of knowing of the victim and she was buried in an anonymous grave. Many years later, she was finally identified as Hélène Zylberszack, a 16-year-old Polish Jew from Anderlecht.

Helene Zylberszac was born in Anderlecht, Brussels, in 1927. In January 1943 she was arrested and sent to the Dossin Barracks. After three months in the Sammellager, she was among the first to be registered on the list for Transport 20 of 19 April 1943. The train stopped for half an hour at Tienen (Tirlemont). Helene (16) alone without her family took her chances and managed to get out of the train. The Schutzpolizei opened fire and she was killed.

School trips, educational tours

The museum plays a role in the Belgian educational system with large school groups coming here during the week. The museum’s mission goes beyond the Holocaust to cover other examples of racism and discrimination. It looks at Rwanda, South Africa, Cambodia. Following a wave of racism at Belgian football games, the museum launched a scheme to provide compulsory tours to football hooligans banned from matches for chanting racist slogans.

The top floor is a bright space for temporary exhibitions with a roof terrace where you can look down into the courtyard of the old Dossin Barracks. Built in Neoclassical style under the Austrian rule, the building was turned into a transit camp in 1942. Abandoned after the war, it was, astonishingly, converted in the 1970s into apartments. The city archives are also based here.

Kazerne Dossin

It took until the 1980s before Belgium began seriously to confront its wartime history. A few survivors such as Nathan Ramet realised it was important to preserve the memory of Kazerne Dossin for future generations. A Polish Jew deported from Mechelen on Convoy VI, Ramet launched the idea of a Jewish Museum of Deportation and Resistance in 1991. Opened four years later inside the Dossin barracks, it is a quiet, reflective place compared to the museum opposite.

The site, renamed Memorial, was given a total makeover in 2019 by the scenographer Antoine Goldschmidt. “The Museum analyses the history,” he said in an interview with De Standaard. “But the Memorial tells you about the victims. It also gives relatives an opportunity to remember the victims who have no grave. It sets out to restore their dignity and their humanity. You see ordinary people doing ordinary things. They could be your family or your neighbours.”

The first room you enter is a dark, unsettling space with victims’ haunted eyes seen through small slits. Then comes a more upbeat room with pre-war music and photographs of Jews celebrating weddings, walking in the sun, eating ice cream. The mood turns darker in a room furnished with two desks and a typewriter. You hear the rattle of the keys as names slowly appear on a ledger. Lining the room, glass cases are crammed with old passports, documents and photographs. The same faces that appear on the memorial wall across the road.

Lives remembered

The 25,000 names were typed out by one woman. Eva Fastag was a 25-year-old Polish Jew arrested in Antwerp in 1942. A skilled typist who spoke fluent German, she was forced to work for the Nazis. As each person arrived, she typed out their name, date of birth and the number they were given on arrival (which determined the train they would be put on).

Fastag did what she could to help by adding the names of Resistance fighters to the lists and helping to smuggle tools onto trains to help victims escape. The worst moment came when her own family arrived at the camp. She had no choice but to type out their names and watch helplessly as they were put on a train. Eva Fastag died in Israel in 2021 at the age of 104.

Irène Spicker

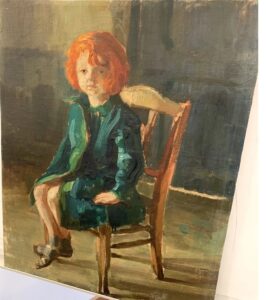

The next room displays simple drawings made by people as they awaited their fate. Most are the work of Irène Spicker, a German Jewish artist who passed the time drawing scenes in the barracks. She sketched the view through a window, a glimpse of sky, and a series of children’s portraits.

The Girl with the Red Hair and the Green Coat

In the basement, a dark brick cellar is filled with photographs of deported children, along with a painting by Spicker known as The Girl with the Red Hair and the Green Coat. This portrait of an anonymous girl was chosen to represent all the young people who passed through Dossin.

The final room is designed like a memorial chapel with a shape forming the Hebrew word ‘Sakhor’ (Remember) placed on a bed of white pebbles. The names of all 25,000 victims are slowly read out in this room. It takes more than 24 hours for every name to be spoken. I listened to a dozen or so. ‘Vos, Lisa, one year old’, was the last name I heard as I left the room.

The Memorial is not a place that lifts your mood. But it does something vital. It tells you about some of the people whose names are marked on the Stolpersteine. You see their faces. Discover their stories. It means they are not forgotten.