On Wednesday, Belgium officially handed over the first birth certificate to a Métis – children (who are now adults) born to Congolese, Rwandese or Burundi mothers and Belgian fathers in one of these countries when they were under Belgian colonial rule – in the town hall of the municipality of Wuustwezel in Antwerp.

Métis are children born in the 1940s and 1950s of an African mother and a Belgian colonial father in the colonised territories of Congo, Rwanda or Burundi. In the run-up to the countries' independence in 1960, the Belgian State abducted children from their mothers because it felt that African women would not raise a child of partly European descent "properly."

"It is inconceivable what injustice the colonial power did to Métis people at the time. These people were discriminated against and stigmatised. The Belgian State is responsible for the lack of birth certificates and must solve this," said Federal Justice Minister Vincent Van Quickenborne in a press release.

As the children were placed in orphanages or foster homes in Belgium without knowing their real families with forged birth certificates, missing or not accepted by the Belgian authorities, many of them – specifically those placed in a Belgian foster family between 1959 and 1962 – still do not have a birth certificate to this day.

Rectifying the consequences of colonialism

Not only is this discriminatory, but it also creates numerous administrative problems for Métis people in question. Therefore, Van Quickenborne worked out a solution with the Board of Procurators General to finally provide birth certificates after decades of discrimination.

"We are now seeing the first results, but I want this problem to disappear as soon as possible, which is why I am calling on all Métis people with missing birth certificates to go to the town or city hall for this," he said, adding that it is the duty of the Belgian State to rectify the consequences of the discrimination and segregation caused by the colonial power of the time.

Preparing a birth certificate can only be done by a municipal authority, which, in these cases, requires a ruling from the family court. "However, it cannot be the intention that Métis themselves have to take legal action against the Belgian State when it is that very State that is responsible for their lack of certificate."

Their mixed skin colour disrupted the colonial order, so the métis children were taken out of society to live separately from the rest of the colony. Credit: MVB

Therefore, the only thing Métis people have to do is register at the municipal or city hall of their hometown to request their birth certificate. If it is missing, local authorities will initiate proceedings and the public prosecutor's office – who will act on behalf of society in the family court – will be notified.

Once the family court has rendered a judgment, the civil registry of the city or municipality will draw up an authentic deed. Since the new circular send out in February 2022, 13 procedures have already been started, Van Quickenborne's office stated.

Related News

- Belgium considers granting mixed-race children full access to colonial archives

- Legacies of the colony: The lost children of Congo

- Belgian State acquitted in trial of abducted mixed-race children in Congo

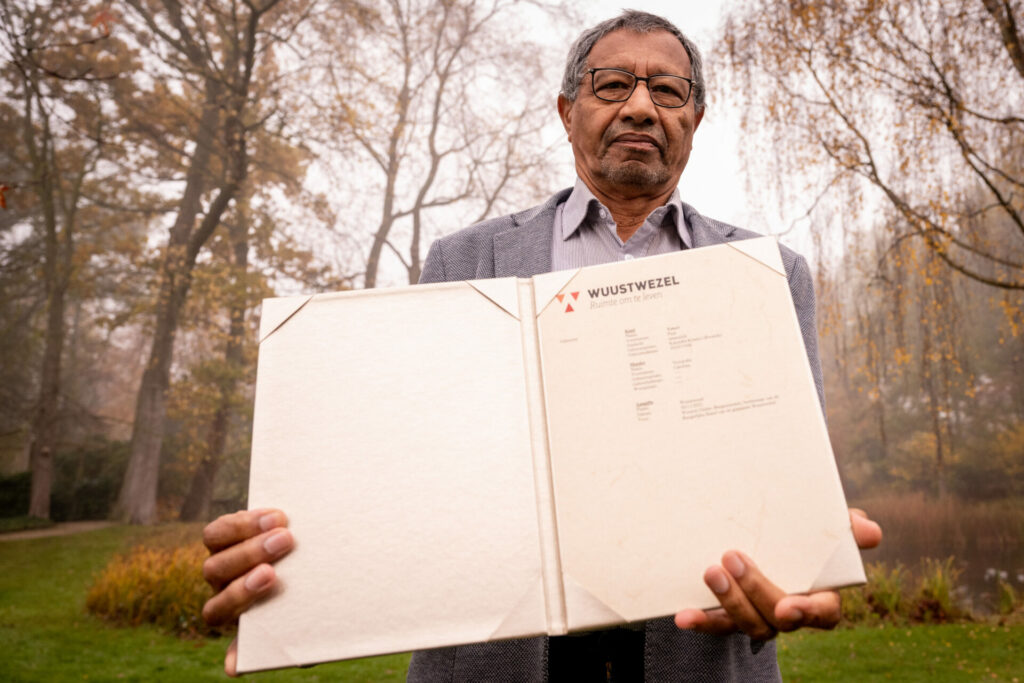

Now, the first new birth certificate through this procedure has now been handed over to Paul Totori, a resident of Wuustwezel. "This is a joyous day for me personally, for my family here and for the community of the Métis children of Rwanda and Burundi. I exist! Finally, officially! On the upside, I find it hilarious that I can consciously witness my own birth," he said.

The mayor of Wuustwezel, Dieter Wouters, who handed over the certificate acknowledged that "erasing injustice is unfortunately impossible," but added that through these birth certificates, "we can symbolically give a name, a face, an identity to the victims of those days. Their story, their agony full of not-knowing, must be told so that the chances of this ever happening again become smaller."