On a cold November day in 1905, European royalty gathered in Brussels to attend the funeral of Prince Philippe of Belgium. Also known as the Count of Flanders, Philippe spent most of his life lingering in the shadows of his older brother, who would later become King Leopold II.

Philippe was physically imposing, with piercing, melancholic blue eyes and glorious sideburns. However, his mild-mannered and gentle character put him in stark contrast with his brother, who infamously seized Congo as his personal colony. Philippe’s story is nonetheless a fascinating study in contrasts.

Philippe was born on March 24, 1837, at the Chateau of Laeken. He was the third son of Leopold I, the German-born prince who became Belgium’s first king in 1831, and his French-born wife Louise-Marie d’Orléans.

As was the custom at the time, the new-born prince was given a long string of names: Philippe Eugène Ferdinand Marie Clément Baudouin Léopold Georges. These were references to his father’s relatives: his grandfather King Louis-Philippe of France and other historical figures, such as various Counts of Flanders and Hainaut named Baudouin who once ruled the many entities that covered present-day Belgium.

Leopold I, who had accepted the Belgium throne in 1831, was from the German Saxe-Coburg and Gotha dynasty, which needed to invoke Belgium’s past to lend a sense of legitimacy to the royal line of the newly created country. Philip was thus given the dynastic title Count of Flanders in 1840. This was a reference to the old County of Flanders, which emerged in 865 when a knight who eloped with a French king’s daughter was given the title of count and a plot of swampy land.

Prince Philippe to the left with his family

Philippe’s eldest brother, Louis-Philippe, died in infancy. He also had a younger sister Charlotte, born in 1840, who would later become Empress of Mexico, and ended her days captured by bouts of insanity in a castle outside Brussels.

Philippe had a fraught relationship with his brother Leopold, then the Duke of Brabant, who enjoyed teasing his sibling with sarcastic jibes. The younger duke had a much closer connection to Charlotte, a relationship that grew stronger after their mother died in 1850. Their father, Leopold I, was a distant parent who even stipulated that his children had to request an official audience before he would speak to them.

Dynastic scheming

In the 19th century, the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha was one of the most ambitious and well-connected royal families in Europe, with members eventually landing on thrones in Britain, Portugal, Mexico and Bulgaria, as well as Belgium. However, Philippe lacked the typical Saxe-Coburg trait of designing grand political schemes to expand the glory of the dynasty – something his brother Leopold certainly embraced.

Until 2014, the monarch’s children automatically became a member of the Belgian Senate when they turned 18, the so-called ‘Senators by Right’. The young Philippe enjoyed the same privilege in 1855. But unlike his brother Leopold, who used the Senate to amplify his colonial aspirations, Philippe never bothered to attend sessions. He found it pointless as politics bored him.

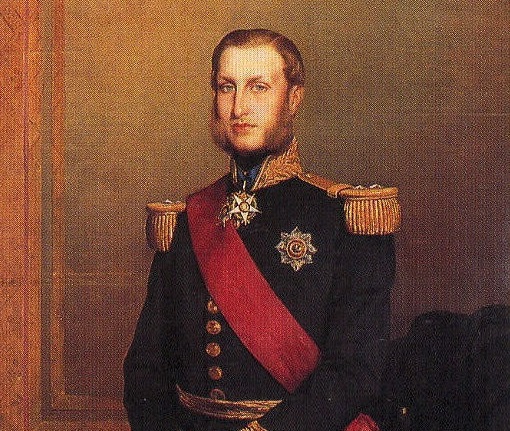

Prince Philippe in full dress uniform

But his political apathy did stop others from making plans for the aloof Belgian prince. His father tried to set him up with one of the daughters of Brazil’s Emperor Pedro II, a proposition Philippe quickly brushed aside. He had no plans to marry at that stage, and he was loathe to cross the Atlantic for a princess he deemed ‘unpretty’.

Still, Philippe was deployed on undemanding diplomatic missions. He attended the funeral of Prussian King Frederick-William IV and the coronation of successor William I. He also turned up at various other royal and imperial courts and often accompanied his father on visits to Queen Victoria. But he rejected a career as a high-ranking diplomat: he hated pomp and circumstance and shunned the limelight.

Despite his aversion to politics, Philippe was keen on military affairs. Unlike his brother, he pursued an active military career, joining the Guides Regiment as a boy, and was appointed a commander of a cavalry regiment at 22. In the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Philippe was even sent to the border to ensure no French troops would cross into Belgium.

By the 1860s, despite his attention avoidance, the prince was targeted by various countries as a potential monarch. In 1862, French Emperor Napoleon III sought him as the husband of his cousin Princess Marie-Isabelle d'Orléans, as a prelude to him becoming Emperor of Mexico. Philippe rejected the plan.

The same year, the Greeks, who had just dethroned the unpopular King Otto I, considered Philippe as their new sovereign. Leopold I, who was offered the same crown in the 1820s, urged his son to accept, but to no avail. Philippe turned the Greeks down, viewing the country as politically unstable (they eventually chose a Danish prince, who became their King George I).

Four years later, in 1866, another offer came in, from the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia – part of modern-day Romania – which had just ousted its Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza. Before even consulting with him, the new governing coalition elected Philippe as their new monarch.

Philippe, of course, never applied for the role and was surprised his name even turned up on the ballot sheet. Once again, he rebuffed the proposition, saying he would rather stay in Belgium. The Romanians then turned to Philippe’s future brother-in-law Carol of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, who did accept the honour, becoming Carol I of Romania.

Marriage, castles, hunting

The year after the failed Romanian project, during his weekly haircut, Philippe’s barber noticed some grey hairs in his sideburns. He was 30 at the time, but the passing reference prompted the prince to consider it was time to marry.

He settled on Maria of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, a member of the Catholic branch of the Hohenzollerns, the dynasty that ruled Prussia and later Germany. The couple wed in Berlin on April 25, 1867. Unlike his brother, he seemed to enjoy a happy marriage: both spent their days sitting in the drawing room where Philippe was reading books and Maria was painting landscapes. The couple had five children, including the future King Albert I, the hero of World War I.

Despite their differences, Philippe and his brother shared a deep love for building and property. Between the Royal Square and the Palais de Justice, along the Rue de la Régence, is a grand palace hidden behind some fences. Currently occupied by the Court of Auditors, which checks the government’s books, it used to be the Palace of the Count of Flanders. This is where Philippe lived until his death in 1905. In 1865, the year Leopold II ascended the throne, Philippe acquired the palace and ordered a complete revamp, including the construction of additional wings.

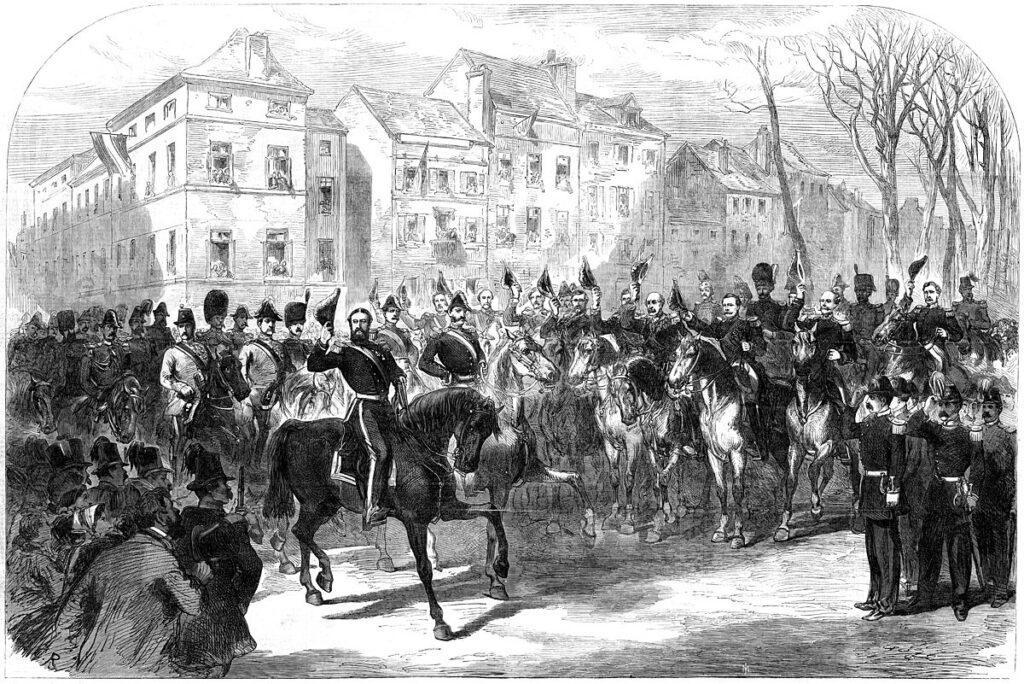

King Leopold II enters Brussels with his brother Philippe, illustration

Philippe later acquired castles and other properties across Belgium and even became a landowner in Switzerland. His pride and joy was the Castle of Amerois in the Belgian Ardennes, which he completely rebuilt after a fire in 1873. He spent many months there indulging in his favourite hobby, hunting (which Leopold II hated), while his wife tended the plants in over seven greenhouses.

Prince Philippe in his final years

Philippe would later suffer bouts of depression. His daughters left home in 1891, while his eldest son and likely heir to the Belgian throne Baudouin died from flu. By that stage, Philippe had already flagged he would refuse the crown if Leopold II, who had no male heirs, would predecease him. He spent his final months at his favourite residence in the Ardennes and appeared in public for the last time in July 1905 whilst attending the World Fair in Liège.

Philippe died on November 17, 1905, at his Brussels residence. Some 250,000 people lined the streets to watch the prince’s final journey to the Royal Crypt in Laeken. Witnesses noticed a weeping Leopold II following his brother’s funeral carriage. It was a rare emotional bond with the brother he barely connected with.