On this day, 1 April 1916, a German firing squad in occupied Brussels executed a 23-year-old Belgian woman, Gabrielle Petit, for working as an intelligence agent for the British during the First World War. Petit's case was not known until after the Armistice, but her heroism in the face of death and repression makes her a national hero in Belgium.

Petit was born in 1893 in the Walloon city of Tournai in a working-class family. In August 1908, she moved to Molenbeek, living near the Chaussée d’Anvers and making two francs a day at L’Ours Noir, a fur store.

By the spring of 1914, she was working at a Brussels cafe and was engaged to a Belgian Army sergeant named Maurice Gobert. When the German invasion came in August 1914, Petit volunteered to join the Belgian Red Cross and Gobert was called up to fight. Injured in the Battle of Liège that same month, Gobert was evacuated to a military hospital in Antwerp. Following the fall of Antwerp to Germany, he found himself behind enemy lines.

Petit helped her husband go into hiding and nursed him back to health. Once recovered, Petit helped smuggle him across the border into the Netherlands, so he was then able to rejoin the Belgian Army via London and was redeployed in Northern France. Impressed by her display of courage, the British intelligence services made contact with Petit, asking her if she would be interested in joining a new British spy network in German-occupied Belgium.

Following training in London, Petit went back to Brussels at the end of July 1915 and was tasked with tracking every movement of German troops in Belgium. She monitored train stations and transmitted information to the allied headquarters, particularly around the Lille and Maubege sectors, writing her gathered intelligence on the back of cigarette papers – ready to be smoked in case she was caught. She used a variety of fake identities, notably Mademoiselle Legrand, the opposite of her real surname.

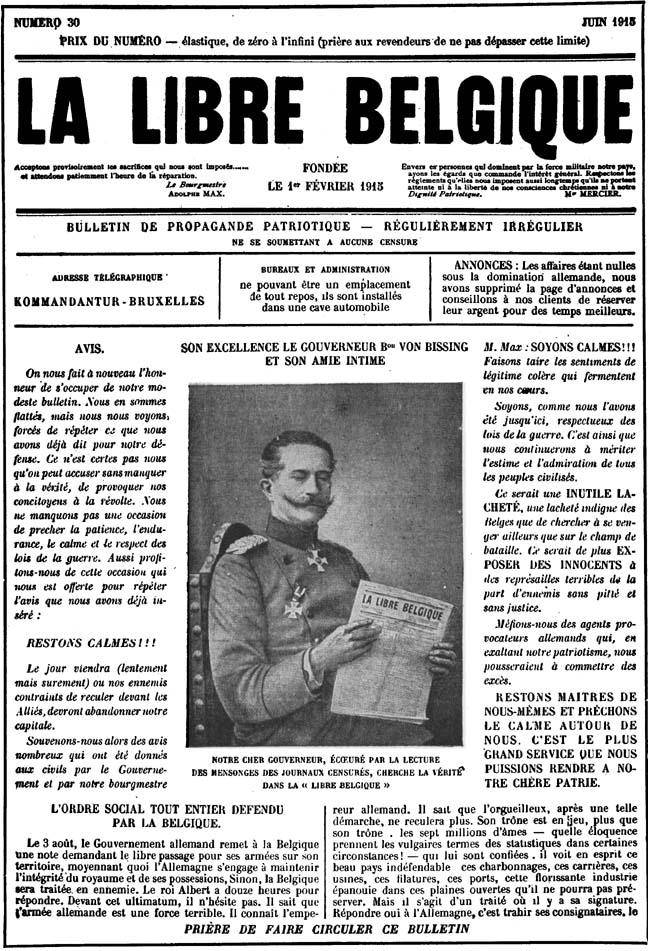

Petit was also active in the distribution of resistance newspapers and pamphlets, including circulating copies of La Libre Belgique, a new iteration of Le Patriote newspaper which had been banned by Germany following the invasion in 1914. She was also part of an extensive underground network, Le Mot du Soldat, which smuggled clandestine mail between Belgian soldiers at the front and their families living under occupation.

June 1915 edition of the underground newspaper La Libre Belgique. The illustration satirically depicts the German Governor-General, Von Bissing, holding a copy of the newspaper.

Her work saved the lives of many soldiers, but eventually, she aroused the suspicion of the occupation authorities. She was arrested and questioned, but for a lack of evidence, was released. Able to continue her missions, she was continued to help Dutch soldiers travel across Belgium and into France to join the fighting. It was in this operation that Petit would be betrayed.

A German policeman posing as a Dutchman tricked Petit, culminating in her arrest on 20 January 1916. She was locked up in the Prison of Saint-Gilles and faced intense daily interrogations by the German authorities. She never gave up any names and put bitter resistance to her intimidations – she was known to bite her interrogators.

Credit: Creative Commons

During her mock trial, Petit resisted under immense pressure from the authorities to give up information about the British spy network. A British newspaper in 1919 detailed exchanges with the judge – her story only became well-known in Belgium and the rest of Europe after the war.

“Why did you enter the service of espionage?” the judge asked.

"From hatred of your system and from a love of my country. But l am not a spy like your spies. You have no business to be here at all. You have broken all your promises and are acting against every principle of justice."

"If you are pardoned, what would you do?" the judge inquired.

"Begin again."

"You were at the head of hundreds of men, who are your agents?"

"Don't you know l am incapable of such infamy."

"Your crimes are enormous. You have been the cause of the loss of thousands of German soldiers."

"You make me very happy. I have taken all my precautions and the service will continue just as though I was there.”

“You will be pardoned if you will only give some indications about your organisation," the judge said.

"No. A thousand times, no."

Petit was sentenced to death on 3 March 1916, and executed on 1 April 1916 at the Tir National in Schaerbeek. As she faced the firing squad, eyes bandaged, she cried out “Long live Belgium, Long live the K….”

A statue, erected in 1923 at the bequest of Belgium and Britain, still stands tall today in the Place Saint-Jean in the centre of Brussels. It was the first statue of a working-class woman, and her status as a Belgian war hero and symbol of the Belgian struggle under occupation, is immortalised.

Queen Elisabeth of Belgium, accompanied by her daughter, Princess Marie-Jose, placing flowers at the foot of the statue of Gabrielle Petit. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

"Today in History" is a new historical series brought to you by The Brussels Times, aiming to take you on a trip down memory lane for newcomers and Belgians alike, written and compiled by Ugo Realfonzo & Maïthé Chini.