With billionaires blasting into orbit and Moon shots back in fashion, the world is on the brink of a new space race. But who knew that Belgium was a pioneer in cosmic adventures?

The country has a higher profile and a more comprehensive presence in outer space than most people, including Belgians, realise. Some of it is literary, some of it is philosophical and artistic and some of it is nuts and bolts science. And a lot of it is sheer persistence.

In 1952, seventeen years before Neil Armstrong, comic strip hero Tintin walked on the Moon. But it wasn’t a smooth journey. Before they were published in two books, Tintin creator, Hergé, would complete pages of the adventure, a few at a time, which were then printed weekly in the Journal Tintin. But after 24 pages, Hergé fell into a deep depression and couldn’t continue. He didn't know what to do with the story. Tintin and his friends were stuck on Earth, the rocket still on the launch pad.

With no progress after seven months, magazine director Raymond Leblanc, having pleading unsuccessfully with Hergé to get back to work, asked him to do an extraordinary thing: write an open letter to the readers explaining the delay.

Hergé complied. He produced a black and white letter peppered with black and white drawings of some of his characters, as well as a striking drawing of himself collapsed in an easy chair completely demoralised. It was a plea for understanding and a frank discussion of his mental state. He wrote that he was not sure how to apologise since "it's both very simple and very complicated". Tintin and his friends, he wrote, "may be tireless, but unfortunately, I am not".

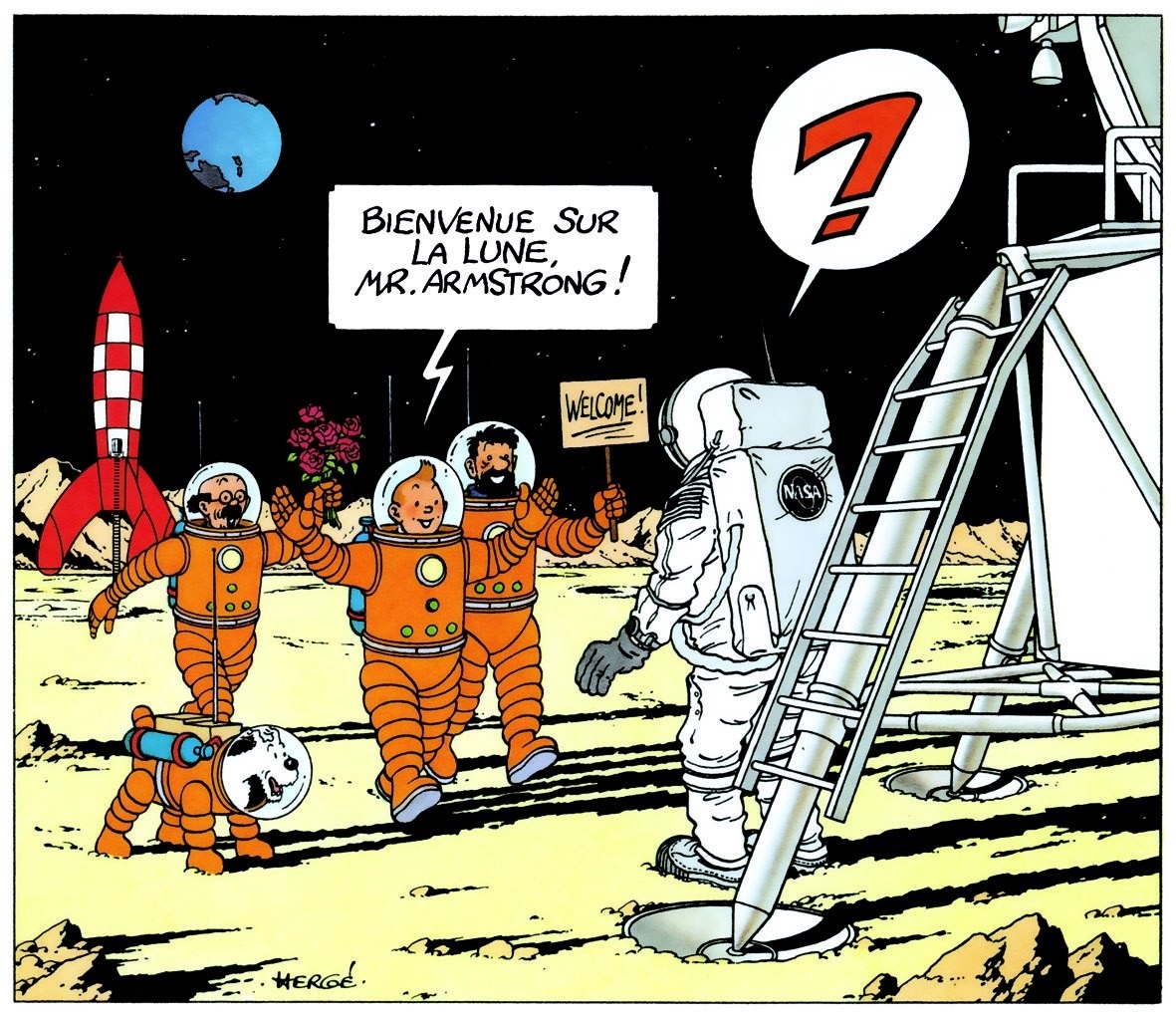

The doctors, Hergé wrote, prescribed complete rest, and he was now feeling better. “I'm slowly getting going again. I promised you the Moon and you will have it!” he said. It took an additional year to continue publishing the story, but finally, after a 19-month hiatus Tintin and his friends did walk on the Moon – and it is still one of the most memorable comic book adventures ever. After Armstrong set foot on the Moon, he drew a special picture of Tintin and his friends welcoming the astonished astronaut.

Fallen Astronaut

Belgium has another artistic connection with the moon. It's little known that there is a piece of human-made art on the Moon and that it is Belgian. The story of how the only piece of art on the Moon got there is full of altruistic impulses but is also fraught with controversy and contradictory claims. It all started at a dinner party at which American astronaut David Scott, soon to take part in the Apollo 15 lunar mission, met Belgian artist Paul Van Hoeydonck.

That evening, they came up with a plan in which Van Hoeydonck would create a small statuette and Scott would place it on the moon. As he recounted in the 2020 Frank Herrebout documentary The Fallen Astronaut, NASA agreed to the project and gave the artist design specs: the sculpture had to be lightweight but sturdy, able to withstand the great heat and cold of the lunar surface, and it could have no apparent gender or ethnicity. The result was a 9cm-tall, stylized aluminium statuette.

Fallen Astronaut, from Apollo 15

When he landed on the Moon on August 2, 1971, Scott placed it face down on the lunar surface next to a plaque that listed the astronauts and cosmonauts who had died in service. He photographed the installation that he entitled Fallen Astronaut. Van Hoeydonck claimed that his purpose for the piece was to celebrate the accomplishments of humankind going to the stars, and he had made a plexiglass display box that would enable the statue to be installed upright. He disavowed any knowledge of the Fallen Astronaut concept. Meanwhile, Scott and NASA claimed that Van Hoeydonck had agreed to remain anonymous, which the artist said was untrue.

After the Apollo 15 crew spoke about the statuette at their post-flight press conference, the National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC asked for a replica to be made for public display. Shortly after, in 1972, working with a New York art gallery, Van Hoeydonck decided to create 950 signed replicas to be sold for $750 each, a second less expensive edition and a catalogue for $5. Scott claimed that this went against their agreement, but the artist said that it didn't.

NASA has a strict policy against commercial exploitation of the space programme and after they complained to Van Hoeydonck, he retracted his permission for the replicas, but not before one had been sold. When it showed up on eBay in 2015, the artist verified the original sale. Fifty replicas had been made and, he said, most of them were still in his possession, unsigned. Meanwhile the original is still lying on the moon, on top of a human bootprint.

Belgians blast off

After Belgian literary characters and Belgian art made it into outer space, it was time for actual living and breathing Belgians to make the journey. The European Space Agency (ESA) was the carrier. Dedicated to space exploration, with a staff of over 2,000 and an €8 billion annual budget, the ESA’s programme includes human space flight, unmanned exploration, launch vehicle design and the operation of a spaceport at Kourou in French Guiana (in January, the ESA helped open a new spaceport at the Esrange Space Centre in Kiruna, in the far north of Sweden, with launches expected in early 2024).

Of the 22 ESA member countries, Belgium was the fifth largest contributor to the budget in 2022, putting €238 million into the organisation, making it second highest contributor per capita. This contribution will rise to €325 million in 2023. Some question such spending in these uncertain economic times, but as Thomas Dermine, Secretary of State for Scientific Policies, says, "Investments in space are very profitable; for every euro invested we get a return of €3.35. Since space is an intensely technological sector it has an outsized effect on the economy. Over 100 Belgian companies have contracts with ESA."

Employment in the sector rose in Belgium by 31 percent from 2010 to 2020, with some 3,600 direct jobs, with the largest European climate research centre set to be located in Brussels. More pertinently, one of ESA's seven cybersecurity centres is based in Redu – which also hosts the Euro Space Centre, a science museum and educational tourist attraction based next to the E411 motorway, devoted to space science and astronautics.

This brings us to the first Belgian in space, Dirk Frimout. He didn't grow up dreaming of becoming an astronaut, though. "When I was a child, it didn't exist, I didn't know about it,” he says. After earning a degree in electrical engineering and a PhD in applied physics, both from the University of Ghent, he did a post-doctorate at the University of Colorado Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics. "Coincidently, it was at that time that ESA decided, in collaboration with NASA, to sponsor, not only pilots but also scientists for missions in space. I thought that this was something for me and since I fulfilled the criteria I went for it,” he says.

Dirk Frimout, the first Belgian in space

Frimout became an astronaut candidate in 1977 and was selected the following year, but it took 15 years before he made it into space. “I was there all the time,” he says. “Everything that I did was in function of that goal that I had. The first time I was a candidate with ESA, they had selected at that moment four men, and they always said that I was the fifth one. But they only wanted four. So I told myself I will continue, I will try to go into space. In the beginning, and as time went by, nobody believed me. But 15 years later I was in space."

While travelling five million kilometres in 143 Earth orbits and logging over 214 hours in space, he took part in a vast array of detailed measurements of atmospheric chemical and physical properties to help improve our understanding of the Earth’s climate and atmosphere. As the first Belgian in space, his mission made him a household name in Belgium with extensive media coverage and Prince (now King) Philippe speaking with him while he was in space, a ticker tape parade organised when he returned Earth and the title of Viscount bestowed on him.

Since his return to Earth, Frimout has directed several research teams in the fields of telecommunications, speech technology and biotech, as well as being a staff astrophysicist for ESA. In 1994 he became the chairman of the Euro Space Society, a non-profit organisation whose mission is to motivate young people in science and space technology.

What struck him the most about his voyage? "What impressed me the most is the fact that you can completely go around the earth in just one hour and a half. That relativises distance, which is very interesting because every time you look at the Earth, you see another part passing by. At some point, you also see the thin atmosphere, and then you realise how fragile the Earth is in that dark and cold space.”

De Winne comes second

Frank De Winne, the second Belgian in space, took a very different path to space. "I was always very interested in combining operational tasks and engineering tasks. That’s why I became an engineer, a pilot and a test pilot. I was still in school, studying engineering also already in the military as a pilot, when I saw for the first time the space shuttle fly to space, and then is when I really said, ‘one day I also want to do that’, and that’s where the dream started."

He has 2,300 flying hours aboard F-16 Fighting Falcons, Jaguars, Mirages and Tornados. While flying in an F-16 over a densely populated area in the Netherlands, he encountered engine problems. His engine failed, as did his main flight instruments and he was seemingly faced with either crashing into the sea or ejecting over the populated area and causing casualties. He managed to land his crippled craft at the airbase from where he had taken off. This earned him the Joe Bill Dryden Semper Viper Award for "a pilot who has demonstrated exceptional abilities", the first non-American to receive it.

He was selected as an astronaut candidate in 1998 and 15 months later he joined the European Astronaut Corps based at the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne. His first space flight, an 11-day mission to the International Space Station (ISS) took place two years later and he travelled to and from the ISS by Soyuz. While on board he carried out a programme of 23 experiments in the fields of life and physical sciences and education. Seven years later he took part in a six-month tour aboard ISS, becoming the first ESA astronaut to command a space mission.

Frank De Winne, the second Belgian in space

One of his key tasks was to operate the ISS’s robotic arm to dock Japan’s first HTV cargo vehicle. He also recorded some video of himself aboard the ISS, which was used as part of rock band U2’s 360° Tour. Since his return he has become a central figure in ESA ISS projects, becoming Head of ESA’s European Astronaut Centre in 2012. Since 2017, he has led ISS operations at ESA. In 2020 he became ESA’s ISS Programme Manager.

Next-gen Belgians

De Winne's central position and Belgium's outsized financial support may have ensured that a Belgian was included in the latest group of ESA astronauts announced last November. King Philippe may have helped too: meeting ESA General Director Jozef Aschbacher, he suggested it would be fitting to have a Belgian astronaut in 2030, the year of the Belgian bicentenary.

Raphaël Liégeois, Dirk Frimout, Prime Minister Alexander De Croo, Frank De Winne and State Secretary for Science Thomas Dermine

Belgium’s Raphaël Liégeois was one of the five finalists chosen from a field of 22,500 candidates, 1,007 of them from Belgium. He has a master’s degree in medical and biomedical engineering from Liège University, a PhD in neurosciences from Paris-Sud University and he did a post-doctorate in neuro-degenerative diseases at Singapore National University.

Since then, he has done research at Lausanne, Geneva and Stanford. He will have at least two years of specialised training, meaning his first flight should be sometime between 2025 and 2030. Neuroscience might seem unrelated to space travel, but one of the areas being researched by ESA is the effect that being in outer space has on the brain.

Liégeois’s physical fitness and his scholarly achievements were, of course, important factors in his selection, but his other activities helped: he pilots hot air and gas-filled balloons and flies gliders. And when he and his wife returned to Belgium after his studies in Singapore, they did a 6,000km bike trip in four months, meeting with hundreds of poets, interviewing and recording them in the local languages.

As for going into space, it has been a lifelong dream. "I don't know why,” Liégeois says. “One doesn't know why a dream is a dream. But I've always had that goal hidden away in a corner of my brain. Growing up, I loved the Tintin adventures on the Moon and recently I've been re-reading and re-reading them."