Ligny Museum is one of my favourites in Belgium. Set amid bucolic surroundings in a converted 17th century farmhouse, it is crammed with artefacts telling the story of Napoleon’s final victory on June 16, 1815, over long-time Prussian nemesis Gebhard von Blücher. Inexplicably, the French emperor allowed thousands of enemy troops, including their never-say-die commander, to escape. It was a mistake that would cost Napoleon dear.

Two days later he met his Waterloo, at the hands of the debonair Duke of Wellington and indestructible Blücher, losing his crown forever and collecting a one-way ticket to permanent exile on remote Saint Helena in the South Atlantic.

Within six years, the once invincible Corsican was dead, aged 51, most likely from cancer but possibly due to poisoning by his British jailers or at the hands of his aide, Charles, Marquis de Montholon, whose wife Albine had fallen under Boney’s spell. The deposed Emperor reputedly fathered her children Napoléone and Joséphine (the names might be a clue). However, the 20-month-old Joséphine died in Brussels after the family’s return from Saint Helena in 1819. She is buried in Evere cemetery.

But back to Ligny. I’ve visited the two-floor museum a couple of times before but still struggle to find it due to the village’s challenging one-way system. I arrive to discover I’m the sole visitor. The museum has opened early for The Brussels Times Magazine.

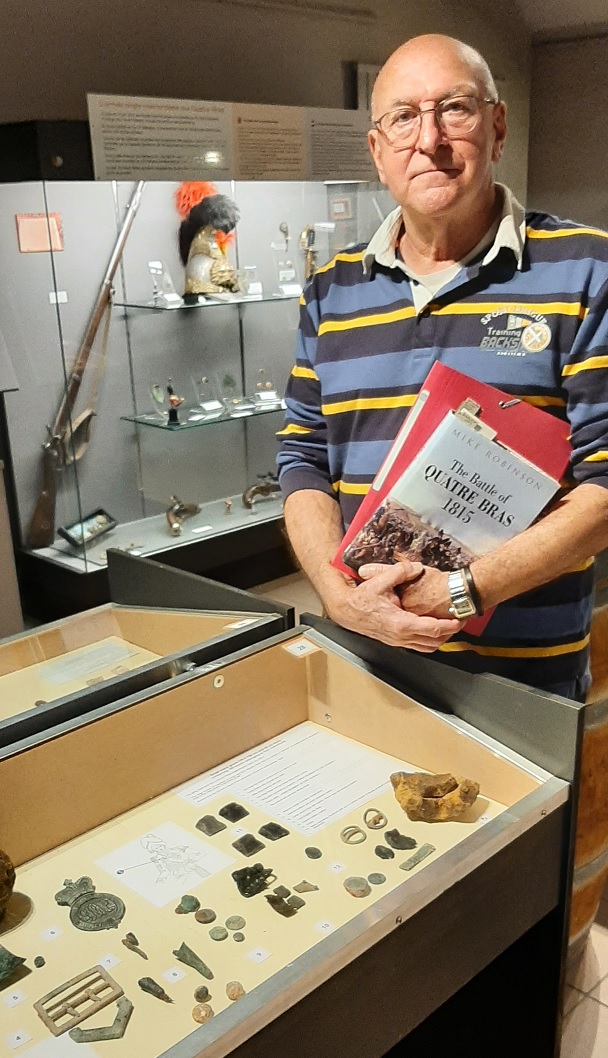

I’m here to meet one of its guides, Philippe Delpierre, a friendly, retired civil servant. He probably knows more than anyone about the thousands of objects on display in the museum – not least because he found a lot of them.

A fanatical metal detectorist, Philippe has combed the Belgian battlefields of Waterloo, Ligny and Quatre Bras (the three engagements were fought in the space of 48 hours) for nearly a quarter of a century. The 72-year-old is out with his super scanner almost every day of the week, in all weather. He has even been known to take his device on holiday to explore Peninsular War sites in Portugal, Spain and along the French border.

His detector has turned up all sorts, from weapons, badges and buttons to discarded empty cans of beer and fizzy drinks. He has also come across human bones.

Around 20,000 men lost their lives at Waterloo, Ligny and Quatre Bras – but despite contemporary evidence of mass burials, only two complete skeletons have been found in the past decade (one last year) and relatively few bones. Historians believe that battlefield burial pits were plundered in the 1830s and the bones were ground for agricultural fertiliser or use in sugar refining.

Close-up of the bones

Philippe is quick to point out that he never looks for human remains. He has only come across them by chance when his detector has signalled something metallic under the surface, such as a musket ball or button, and has found bones alongside them, he explains.

One such find was a group of bones he discovered near the Lion’s Mound at Waterloo, where Wellington’s infantry formed squares to fight off repeated assaults by the French cavalry and Marshal Ney. The bones were mixed up with Brown Bess rifle parts, coins and metal plates bearing the insignia of the First Regiment of Foot, famed for its role in repulsing the Imperial Guard in the battle’s closing stages.

Curiously, a button belonging to a French artilleryman was also among the objects, despite history telling us that French gunners were never close to the position where it was found.

Philippe, whose story is being revealed here for the first time, along with other individuals who agreed to be interviewed (their identities were under wraps until now to avoid arousing sensitivities), has always kept a meticulous record of his finds and their precise locations.

“I can tell you exactly when I found the ‘English’ bones. It was December 21, 2002,” he says. “The bones showed signs of having been thrown pell-mell together in a hurry and were jumbled up. I had the impression they’d been moved from their original burial place.”

So, why did Philippe keep the bones? He was waiting for the right moment. “My only wish in all the years since was to see them placed in an ossuary, with a proper military send-off, perhaps involving re-enactors. A ceremony with rolling drums, the presenting of arms, the laying of wreaths. These men fought in atrocious conditions and died in a terrible way. They deserve a proper tribute.”

However, he says his hopes were frustrated by Belgium’s complicated regional bureaucracy which meant no-one would take responsibility for allowing a reburial.

“I couldn’t exhibit the bones in a museum either due to potential objections,” he says noting the calls to remove the skeleton at Le Caillou, the museum based at Napoleon’s last headquarters in Genappe, in case it upset children. “It makes you wonder what people would say if they saw the Douaumont ossuary at Verdun!” he adds, referring to the First World War memorial where the bones of more than 130,000 unidentified victims are visible.

So, despite realising he had made a significant find, Philippe felt he had no choice but to wait until the authorities eventually provided a fitting burial place. Meanwhile, he safeguarded the bones in a box in the loft of his home at Montigny-le-Tilleul, near Charleroi.

At the end of last year Philippe learnt that Pierre d’Harville, one of the founders of Ligny’s museum, who also had a collection of bones in his attic, was handing them in for scientific analysis. Philippe decided to follow suit.

Philippe Delpierre

He was contacted by Dominique Bosquet, an archaeologist with the Walloon Heritage Agency (Agence Wallonne du Patrimoine, AWaP) and Waterloo Uncovered, a charity which carries out battlefield digs with military veterans suffering from life-changing injuries and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“I was amazed that Philippe had kept the coordinates of all his discoveries, not just the Lion’s Mound bones,” Dominique says. “We’re talking of about 2,000 finds altogether. We immediately started work on overlaying all the coordinates on Google Maps.”

The pair have compiled a joint report – providing an exclusive preview for this article. It focuses on Philippe’s discoveries in the area where the Battle of Waterloo reached its climax, as the Chasseurs à pied and Grenadiers launched their final desperate assault at around 7.30pm. They were within 50 paces of Wellington’s smoke-covered line when the Duke shouted his famous order – “Now’s your time!” – the signal for the British redcoats to leap up in four ranks, firing a series of shattering volleys, before leading a bayonet charge with the Dutch-Belgian Detmers brigade to rout the previously invincible Imperial Guard.

Philippe’s finds, including buttons from the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards, Royal Regiment of Artillery and Royal Horse Artillery, unambiguously confirm historical accounts of where the allied units were deployed. His finds relating to the French, however, present a more surprising picture, with buttons from corps who were not involved in the final attack – or not even thought to be at Waterloo at all.

The report, which will appear in the Chronique de l’Archéologie wallonne, has an explanation for this. After his escape from Elba, Napoleon had to reform his army quickly as the allies moved against him. His troops were issued with whatever uniforms and equipment came to hand, so it is probable that more than a few were wearing kit from regiments which were not present on the day.

The scale of Philippe’s discoveries – far from evident given the intensive farming (and looting) which has taken place ever since the battle – astonished Dominique. “The fact that 200 years of agriculture hasn’t disturbed the spatial distribution of the finds was a real surprise for me, encouraging us to go on with our research,” he says. The pair already have a second paper in the pipeline with Dominique’s colleague Véronique Moulaert and Caroline Laforest from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences.

Before teaming up, however, Philippe and Dominique had to get round a potentially delicate issue. Philippe did not originally have a permit to use his detector in Wallonia and felt uncomfortable about this, according to Dominique. “Everything is now in order. We’re not a punitive organisation: anybody who wants to collaborate with us is welcome to, as long as they put themselves in line with the law,” he adds.

The Lion’s Mound bones, together with a skeleton unearthed last summer by Waterloo Uncovered near Wellington’s field hospital at the Ferme de Mont-Saint-Jean, are undergoing analysis at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels (more of which later).

At the museum, Philippe briefly halts our private tour to take out his wallet and show me his new permit. It’s a vindication of his tireless efforts to uncover the past. He then returns with enthusiasm to explain the museum’s impressive display of regimental buttons, 99 percent of which he personally dug up or acquired.

Philippe is married and I ask how his spouse feels about his hobby/obsession. “My wife is delighted to see me practising a passion which allows me to stay in physical and psychological shape,” he smiles. I only leave after more than two hours, promising to return soon.

Pierre’s story

A key figure in the launch of Ligny’s museum, 83-year-old Pierre d’Harville is a noted expert on the Belgian campaign of 1815. Former director of the Académie royale des Beaux-Arts in Charleroi, he is also the author of Napoléon à Waterloo (published 1965) and Vice-President of the Royal Belgian Society for Napoleonic Studies (Société royale belge d’études napoléoniennes).

“His” bones had a more complicated provenance.

Pierre says they were given to him by the historian Jacques Logie about 20 years ago, after they opened the museum, having been found at Plancenoit, the scene of bloody skirmishes during the Battle of Waterloo. They were thought to be Prussian. “We didn’t end up exhibiting them for ethical reasons,” Pierre says.

For years, he thought there were only two skeletons because there were two skulls. “I tried to put them together with an archaeologist but later discovered that the bones belonged to more than two individuals,” he says. “My idea was to give them a proper burial with a ceremony. I thought about the ossuary in Genappe, but the Brabant Wallon authorities didn’t want to do this. At some point, the bones were sent to the UK for a planned museum, but it didn’t open and they were returned to me.”

In May 2015, with the approach of the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo, Pierre contacted a friend, Dr Nathalie Vanmuylder, a lecturer at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB) laboratory of anatomy, biomechanics and organogenesis (Laboratoire d’Anatomie, Biomécanique et Organogenèse).

Reenactors by the Lion's Mound

He sent her some of the bones to examine. Dr Vanmuylder analysed them with a ULB colleague, Mathilde Daumas. They wrote up their findings – which were not publicised beyond the university – and returned the bones to Pierre.

Some years later, in November 2022, Pierre attended a lecture at the Waterloo Mémorial by Belgian historian Dr Bernard Wilkin. It focused on Bernard’s bombshell research with British archaeologist Professor Tony Pollard and German historian Rob Schäfer, which revealed that bones harvested from European battlefields during the mid-19th century were used to turn brown sugar into white.

Indeed, a large sugar factory was built close to Waterloo’s battlefield in the 1830s. The exploitation of bones by the industry was well-known at the time. A German-language newspaper, Prager Tagblatt, warned its readers in 1879 to use honey rather than sugar to avoid the risk of “having your great-grandfather’s atoms dissolved in your coffee”.

At the end of Bernard’s presentation, Pierre approached him and announced: “I’ve got Prussians in my attic.”

The historian collected the bones from Pierre’s home in Sart Dames Avelines and took them to the city morgue in Liège, where they are undergoing forensic and anthropological analysis by Professor Philippe Boxho from the University of Liège and Mathilde Daumas from the ULB.

Jacques’ story

The ‘Prussian’ bones were rescued by the late Jacques Logie, a lawyer, politician and author of several historical works about Napoleon and his last battle, including his magisterial Waterloo: The 1815 Campaign, published four years before he passed away in 2007.

One of his sons, Philippe, a film producer in Brussels, explained what happened. “One Saturday morning in 1974, a neighbour called my parents to tell them that he’d seen bones appear during construction work in front of his house, near the little bridge over the Lasne in Plancenoit,” he says.

When he told his parents, they sprang into action. “They put on their gloves and boots, went to the site and, indeed, saw fragments of bones in the mud. They managed to extract what appeared to be the bones from two corpses – there were two skulls – as well as shreds of boot leather and pieces of cloth.”

His father was “certain” that the bones were those of Prussian soldiers. One skull, the least damaged, was passed to an acquaintance at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. It was analysed, but no written record remains.

Some years later, Logie senior sent the bones to a member of the Waterloo Committee for a museum in Kent, but the project was abandoned and the bones returned. “My parents thought about taking them to the ossuary at Le Caillou, but felt it wasn’t really appropriate as it was more a place of French remembrance,” Philippe says.

Later, there was a plan to create a museum dedicated to the Prussians at La Belle Alliance, a former inn on the battlefield, where the remains could rest there, but that never came to fruition either. “The years passed and my father almost forgot about the bones which were stored in the attic, except for one of the skulls which he kept in a glass case in his office, with other souvenirs of the battle. When Pierre launched the Ligny museum, my father entrusted him with the bones, except for this one skull,” Philippe explains.

After the meeting between Bernard Wilkin and Pierre d’Harville, the Logie family were persuaded to hand over the skull, which appears to bear signs of a horrific death. “We’d like it back afterwards as we’re the legal owner, but it’s not our intention to impede the research and archaeological significance of this re-discovery,” says Philippe.

Caroline’s story

Caroline Laforest, a 37-year-old French osteoarchaeologist based at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, was part of the team which unearthed the skeleton at Mont-Saint-Jean last summer.

After hours of painstaking work to remove soil from the bones and carry out measurements, the skeleton was transferred for further research to her offices, behind the dinosaur museum in Brussels. She is also examining the bones found by Philippe Delpierre.

We meet in Caroline’s office, off a corridor cluttered with stuffed animals and crates. It’s all a bit Indiana Jones. I’m at least expecting to see a fancy mortuary fridge. Nope. Instead, the skeleton is laid out on a large wooden shelf under Caroline’s window, a perfect fit. The Lion’s Mound bones sit on another shelf, with a sink in between.

Caroline Laforest, from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences

I start by asking about what she’s learnt so far. “I’m still studying the skeleton, but we know it’s a man, of course. You can tell that from the hip bones. They’re longer than a woman’s, while the pelvic belt is smaller because men don’t give birth. In terms of age, I’d say he was in his late 20s, possibly early 30s.”

She takes a toothbrush from the sink and gently removes some debris from his teeth, which look in remarkably good condition. It’s perhaps surprising he still had them as ‘Waterloo heroes’ teeth’ were sold as dentures for years after the battle.

Caroline is working with a contact in Lille who’s an expert in cementochronology, a method for assessing age at death from dental tissue. “It’s a bit like trees: a new ring appears in your dental cementum every year. If you go into the tooth root, you can see the light and dark rings. By counting them up you get a more accurate age range,” she explains.

The soldier was about 1.75 metres tall. Even without a full skeleton, height can be estimated based on the length of the femur (thigh) or tibia (shin) bones – “but there’s always some variability”, she says. “The bones in the spine show irregularities which means he could have suffered from postural problems and/or used his back a lot. We don’t know what killed him though.”

The next stage of Caroline’s research is likely to involve isotope analysis, which indicates geographic background and diet.

“From teeth, we can tell where someone grew up,” she says. “Once a tooth has grown, the information stays inside. The bones in the rest of the body tell you about the past 10 years of a person’s life, for example, what they’ve been eating or drinking, because the bone tissue is renewed every decade or so.”

Caroline says it’s easier to spot the difference between places which are far apart. “For example, if you’re comparing someone from, say, the north of Scotland and a person from Corsica, because their diets would have been very different. But it’s more difficult to draw conclusions if you’re comparing individuals from either side of a frontier. If you lived in the north of France or the Low Countries, you’d have a similar strontium level.”

Turning to the bones found by Philippe near the Lion’s Mound, Caroline confirms his theory that the remains were moved and reburied. “A lack of smaller bones, which are easily lost when they’re moved, indicates this. But I can’t say why they might have been moved.”

I ask what will happen to the skeleton and other remains once the tests are complete. “It’s under discussion. I’m in favour of reburial in a place which would allow us further access to the bones in 10 or 20 years if scientific progress enables us to tackle questions we can’t answer now,” she says.

Mathilde’s story

Mathilde Daumas, a 33-year-old anthropologist and anatomist, is studying the ‘Prussian’ bones. She also works at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, next door to her compatriot Caroline Laforest, and at the ULB’s faculty of medicine, where she teaches as part of her doctorate.

She’s quick to point out that she is not a Waterloo buff. “I study medieval bones and, specifically, their muscle attachments,” she says. This sounds niche, to put it mildly, but Mathilde explains that by examining the muscle grooves still visible on the dry bone, anthropologists can get an idea of the activity levels of different groups and, by extension, of the lives of most ordinary people at the time.

A set of neatly boxed bones on her shelf catches my eye. They’re not the Prussians, but the remains of medieval monks from the Abbey of the Dunes in Koksijde. “They’re what I’m usually studying. We use some of these bones for reference when comparing other finds,” she explains.

Mathilde confirms that this is not the first time she has seen the Prussian bones. “When I opened the box they were in, I immediately realised that I’d examined them, or at least some of them, in 2015 with my ULB colleague Dr Vanmuylder. I recognised them because they had labels on them stamped ‘Museum of London Department of Urban Archaeology’, dating from an examination in the 1970s.

“But we now have at least 12 more bones than I’d seen previously, as well as a ribcage and feet,” she says, including a second skull loaned by Philippe Logie. “Originally, we knew the bones belonged to at least three individuals – because there were three left legs. The additional bones indicate that we now have four individuals, possibly five. At this stage, we can say they’re probably all male and aged from their early 20s to 50. They were between 1.60 and 1.70 metres tall.”

However, she does not have what archaeologists call ‘context’, which is detailed information about the environment in which the bones were found or how they were buried. “When bones are moved, you can’t put them back in the exact same position. Therefore, information about a body at the time of death is lost. It’s also very difficult to ‘reassociate’ the bones with the right individuals. In many cases, the smallest bones disappear because they were missed in the field by the people recovering them,” she says.

A couple of weeks after we meet, Mathilde and her head of department at ULB, Professor Stephane Louryan, are able to carry out 3D scans at Erasme Hospital in Brussels on the white and brown skulls found with the bones. “We were lucky to have access to the scanner when there was a gap between patient appointments,” she says.

Initially, it was thought that the brown skull showed evidence of a savage injury caused by a blow in the face from a sword or bayonet. But the preliminary CT scan results suggest a different diagnosis. “A tooth which had initially appeared to have been crushed is in fact still complete in what was the individual’s gum. It just hadn’t grown. Sharp cut marks on the vertebrae, however, show signs of trauma possibly caused by stabbing.”

I’m curious why one skull is white and the other is brown. “It could be from where the bones were buried. Even where remains are found close together there can be significant differences in the make-up of the earth. It’s also possible that the skull was varnished at some point. We know it was manipulated because the mandible [lower jaw] is attached to the rest of the skull by wires.”

I wonder to what extent Mathilde connects the bones with a person who had a face, who lived, who laughed, who probably had a sweetheart, and a mother worrying about him at home. “When I scan the skulls, I place them very carefully and I talk to them. I’ll say, ‘I’m going to put you here, ok?’” she says. “When we’re looking at the results of the scan, I’m focused on the findings. Inevitably you’re then thinking less about the individual and more about what the results show.”

Despite research suggesting that bones on Belgium’s battlefields were plundered long ago, Mathilde believes more individual graves will be found. “Local people have been finding bones ever since the battles took place: we have numerous testimonies,” she says. “What’s changed, however, is that thanks to science we can now potentially say more accurately where these men were from, what they ate, what they drank, how they lived and how they died.

The way society looks at remains has also changed. It was only in the 20th century that it became commonplace for soldiers to have individual graves. A project to build a new memorial is being considered for recent and future discoveries [see below].

Bernard’s story

Bernard Wilkin, a 41-year-old historian based at the State Archives in Liège, is the author of nearly a dozen books including Fighting the British: French Eyewitness Accounts From The Napoleonic Wars (2018) and Lettres de Grognards: la Grande Armée en campagne (2019). He has also written or contributed to numerous studies, including the report which revealed that the ‘missing’ Waterloo bones were almost certainly exploited by the sugar industry.

Bernard played a key role in ensuring that the Prussian bones were put in expert hands. He believes that relics are probably still to be found in local homes and wants to encourage ‘owners’ to hand them to the appropriate authorities so that they can be “looked after properly”.

Mathilde Daumas and Bernard Wilkin

“We have been blessed with the forensics team,” says Bernard. “They love history.” They are carrying out a battery of tests, including C-14 radiocarbon dating to determine the age of the bones, DNA, strontium isotopic analysis, as well as facial reconstruction.

“It's exciting to have the prospect of putting faces to the ordinary private soldier instead of always focusing on colonels and generals. The DNA tests raise the possibility of finding descendants of these men via genealogical databases,” he adds.

Asked how he reacts to those who might feel the war dead should be left in peace and not subjected to such analysis, Bernard says he understands the concerns and why the study of the bones makes some people uncomfortable.

“Every time I have a skull or a bone in my hands, my first thought is not about the research that it might trigger but about the poor lad who ended his life in Belgium,” he says. “I don’t feel conflicted about collecting the bones though because my goal is to save them from private exhibition and offer them, after 200 years, a chance to have a dignified burial with military honours and a beautiful monument. For me, this is a sacred mission that is more important than the research itself.”

Bernard is involved in talks with the Belgian authorities, Waterloo Uncovered and his research partner Rob Schäfer about creating a new monument to house the British and Prussian remains. They’re planning to create an ossuary at Hougoumont where French infantry led by Napoleon’s brother Jérôme fought hand-to-hand against the British Guards and their Germanic allies. “It would be a memorial for all nationalities,” he comments.

Rob, author of The Iron Time, a German military history newsletter, admits that he would have preferred for the Prussians to be interred closer to where they fell at Plancenoit, near the Prussian memorial erected in 1819.

“Unfortunately, it seems that the local community doesn’t want anything to do with the idea so Hougoumont is the best solution,” he says. If the ossuary does not materialise, Rob says the German War Graves Commission (Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge) has offered to provide burial space in its cemetery at Lommel.

Bernard, however, is confident that the Hougoumont ossuary will see the light of day – and that it will be designed to allow scientists to have access to the bones, if needed, in future.

Museums hope new Napoleon biopic will boost numbers

Museums in Belgium linked with Napoleonic wars and the 1815 campaign are hoping for a boost in visitor numbers, thanks to the upcoming release of Ridley Scott’s much-anticipated biopic of the French emperor.

Joaquin Phoenix, winner of the best actor Oscar for Joker in 2020, appears in the title role, while Vanessa Kirby, known for playing Princess Margaret in The Crown, will portray Empress Joséphine.

Co-produced with Apple Studios, the historical action epic is said to capture Napoleon’s famous battles, ambition and visionary mind. Your writer was lucky enough to see a sequence from the film at Cinemacon, where Hollywood studios showcase clips from films in post-production. The sequence featured a visceral depiction of the Battle of Austerlitz.

Still from Ridley Scott's Napoleon, with Joaquin Phoenix (centre) as the emperor

Still from Ridley Scott's Napoleon, with Joaquin Phoenix (centre) as the emperor

The movie is tipped as a future award winner. Scott, who at 85 shows little sign of slowing down, already has three Oscar nominations for best director under his belt – for Thelma & Louise, Gladiator and Black Hawk Down – but is yet to pick up the coveted statuette. Joaquin Phoenix was also nominated as best supporting actor for his portrayal of Commodus in 2000’s Gladiator, which won five Academy Awards including best picture and best actor for Russell Crowe.

Like Ligny, the Domain of the Waterloo 1815 Battlefield (Domaine de la bataille de Waterloo 1815) is among the museums hoping that the movie will spur a surge of interest in Belgian sites associated with Napoleon.

Director Thibault Danthine admits that the complex could do with a shot in the arm, with visitor numbers still 10 percent below pre-Covid figures. “In 2019, we had just over 160,000 visitors and the site normally welcomes a lot of foreigners – around 70 percent of the total. But they’re not all back yet. The film could help.”

Napoleon is due for release in cinemas on November 22 and will later stream on AppleTV+.